Home > Directory of Drawing Lessons > Art Principles & Elements > Art Composition > Lessons in Art Composition

Art Lesson in Composition : Learn How to Arrange Things & Figures in Picture to Create Beautiful Compositions

|

|

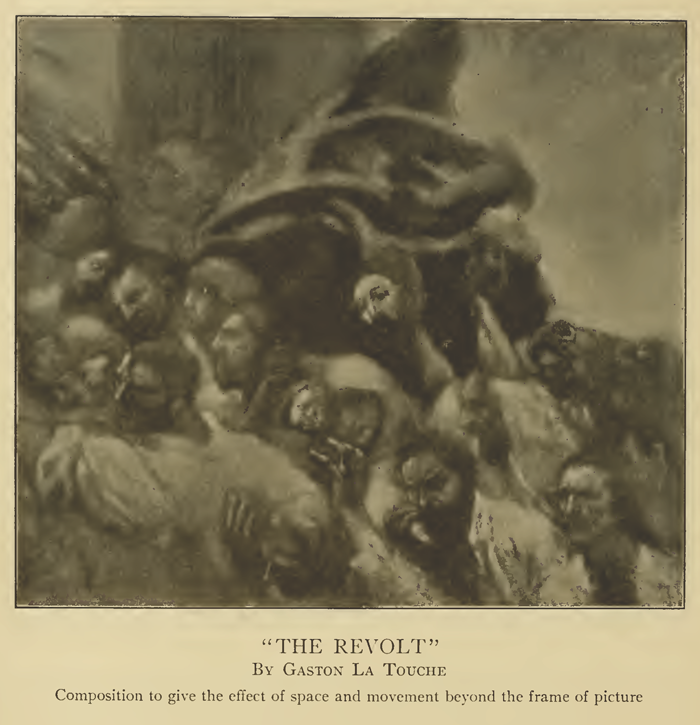

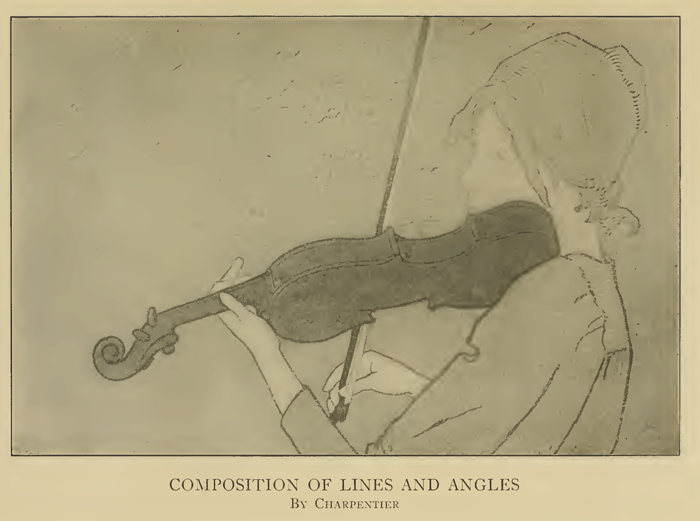

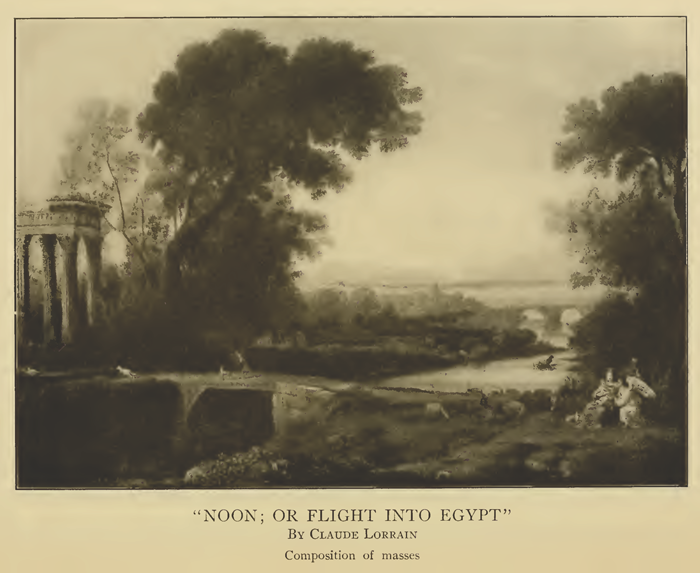

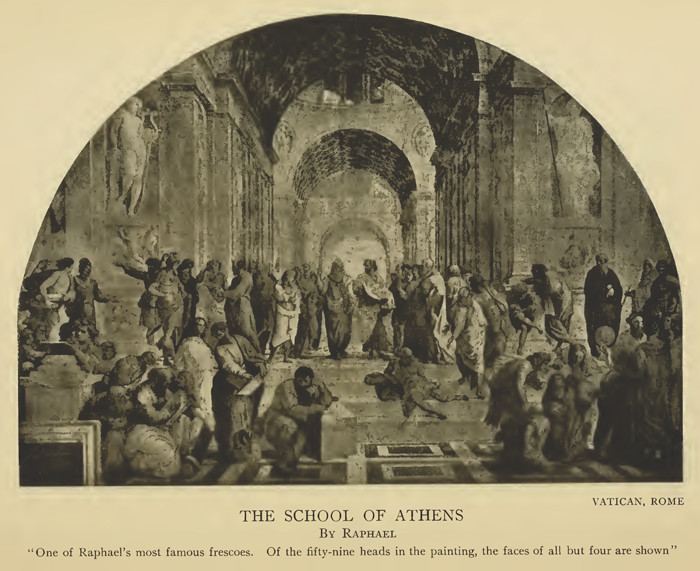

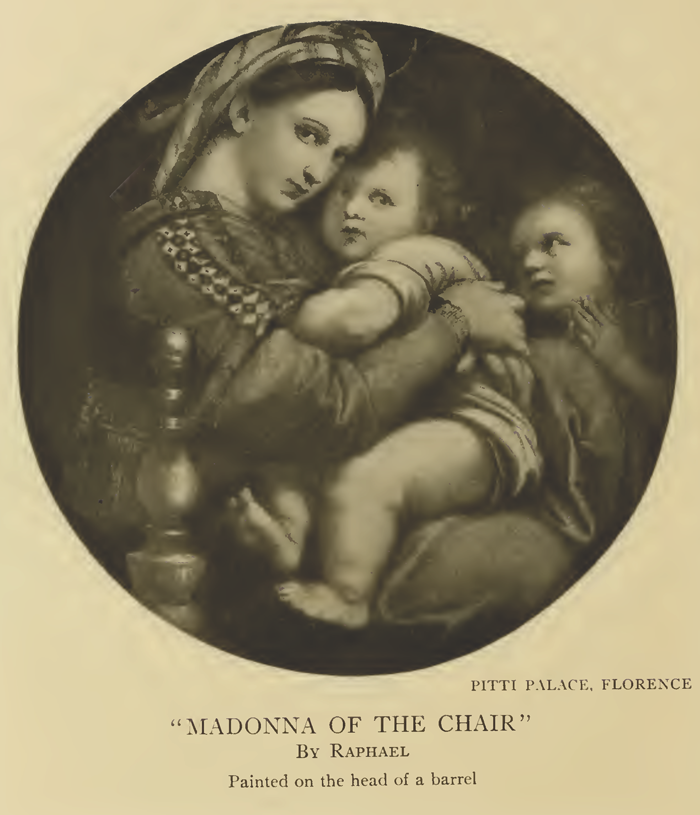

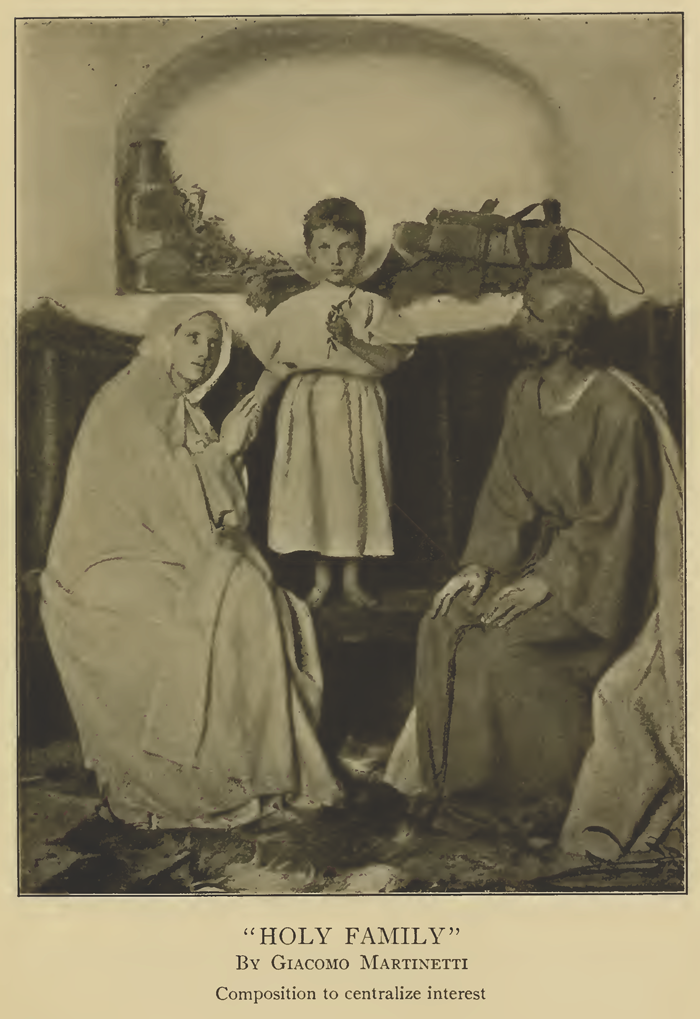

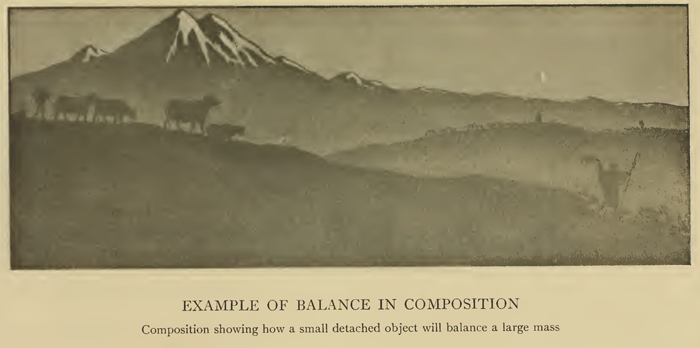

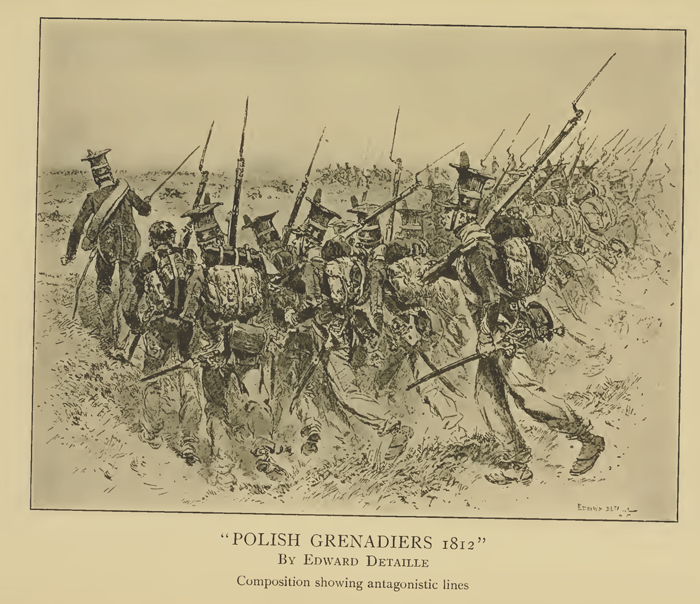

The text above is actually made up of images, so if you need to copy any text, you will find it below. Thank you. LESSONS IN ART COMPOSITIONThe artist's intention should be apparent above all else in a picture and the arrangement of a composition be such as to make it immediately understood. To be obliged to look at one part and then at another, taking the sum total of information upon which to base a conclusion, is confusing. There should be one dominating feature, and the other incidents take their places in relation to it. Objects thrown together haphazard will not make a picture, no more than is an incoherent jumble of sentences literature. There must be an orderly plan of procedure. The theme, the main incident, the principal figure or the climax, whatever you care to designate the fundamental idea, must be easily comprehended. For example, take the sentence, " A man is plowing in a field." Man is the substantive, plowing the predicate. Every word has a clear relationship, directly or through other words, to the principal noun or the principal predicate —that is, to the main subject, man, or to the main action, plowing. In a painting of the incident, the horse, the sky, the trees, the distance all have a qualifying relationship to the man plowing. The size of a painting is decided upon before proceeding with the composition. Various considerations influence the artist in determining the dimensions of his canvas, but the most reliable guide is the requirements of dignity. If a man wishes to represent nature on a grand scale he should conceive in a large way and have plenty of space to work in. The portrait of a splendid figure in the fulness of power ought not to be cramped into a small area, and a trivial subject is not exalted by making a large painting of it. It was a principle with the old masters to show as much of a figure as possible. Almost without exception they give a complete representation of the head. Raphael's " School of Athens " contains fifty-nine heads, all but four showing the faces. Rembrandt observed the principle even more rigidly than Raphael. In his " Hundred Guilder " print there are forty figures, and every face has a history written in it. Careful design is conspicuous in the works of the old masters. Sometimes it is in the arrangement of lights. Again, it is in the beautiful interweaving of graceful lines. In some pictures we distinguish the convolutions of a scroll, and in Raphael's " Madonna of the Chair " the lines yield to the exigencies of a barrel head upon which the picture is painted. The composition of line is based upon the principles of ornamental design, the lines returning into one another, leading the eye pleasantly from point to point. A vortex of lines within a space is a simple device in composition, either for the oval, the round or the rectangle. Another kind of composition is starlike, the lines radiating from a center. When the architectural lines or the furniture and subordinate objects are not complete within the frame and extend beyond the limits of a picture the scheme suggests by a part a much larger whole. If the artist wishes to express the personality of a figure he will centralize the interest upon it, but when introduced incidentally it is the means of directing the eye to something more important. Composition to centralize interestThere are various ways of calling attention to a particular part of a composition : Lines pointing directly toward the object will accomplish the result ; the frame of a window will compel the eye to dwell upon that which is within the space ; a form may be repeated on either side of the thing to be emphasized, and when everybody in a picture is looking at an object, naturally we, also, will look at it. If the artist takes up his station on an eminence —a hill or mountain —the horizon will be high in the picture ; if he lies on the ground the horizon line in the picture will be low. By framing a portrait so that the head of a figure comes nearly to the top the individual will look like a tall man. If you leave much space over the head he becomes a short man, regardless of his actual stature. The old portrait painters used to put the horizon line knee high in their compositions and the effect was heroic. Balance means equality of weight but not necessarily equality of volume. A small body on the long end of a steelyard will balance a large body on the short end. In picture-making a large mass on one side of a picture is balanced by a small isolated spot at the other side. A strong light on one side of a composition is balanced by a gradation of lights on the other side. A candelabrum on each end of a mantel shelf balance, but there are many ways to secure balance without resorting to duplication. A figure or an object placed exactly in the center of a canvas is balanced, but when removed to one side of the picture the impression of emptiness which would be left may be overcome by the introduction of a very insignificant detail, such as a fold of drapery. EXAMPLE OF BALANCE IN COMPOSITIONComposition showing how a small detached object will balance a large mass Two or more lines are in rhythm when they run the same way, but they are antagonistic when opposed to each other. Antagonistic lines are useful in establishing equilibrium. For instance, soldiers when marching in review all lean forward, but the shouldered guns slant in the other direction and counteract the effect of men falling on their faces. The diversity of methods of composition employed by the masters of art renders it difficult to state any preference for one over another. That which has succeeded most effectively in one example may prove embarrassing to the student in working out a similar problem. Rather seek a process suited to your own peculiar needs and capacity than to force upon yourself rules which may not be adequate to the practical end, however they may be recommended by high authority. One finds in Japanese pictures a certain spontaneity which is very compelling. The designs are like fragments of song wafted to us on a vagrant breeze, tempting and promising. There is an individuality and a simplicity of composition in the art of Japan, forceful and most direct in its appeal. Even the fantastic figures are so cleverly arranged that we overlook the grotesque drawing. To be sure, the unusual is to be sought for in composition, but an apparent straining for sensational effects is to be deplored. The highest phase in art is the expression of the imagination. Semiconsciously the innumerable impressions evolved by the memory are blended by the artist into an idea which can be said to be original, but imaginative pictures must necessarily be based upon the knowledge of natural form. We deal with a living world, and if an artist succeeds in giving us the essence and character of things we may be lenient about technique. There is no formula for painting ; to make the pupil understand what he sees is the most that any master can hope. It may be that one artist delights in the dextrous application of his medium ; to another it is the subject which appeals, and to others it is the narrative or story-telling quality. " Style " is the expression of this individuality, and style may be acquired. But it is never to be considered as the ultimate aim. It may be taken as proof that the painter or illustrator, by hard work, has lifted himself to a position where he convinces others that the conception and production of his pictures are personal. For this reason we should not harken back to any period or to any master, but endeavor to discover new fields, new ways of getting results. Every step in the progress of art has been in unexplored territory, and if the discovered principle was worthy it has lived. The simple and unaffected indicate greatness. The painter who is everlastingly trying to do the sublime will stumble over the little things which constitute sublimity. There is no masterly handiwork without the masterly thought behind it. There is no such thing as inspiration. Good work is premeditated, truthful, sure, and when done can be done again. It may not be amiss to advise the pupil to carefully look after his bodily health, as any physical disturbance interferes seriously with the mental processes. Distraction caused by a disordered system will hamper and clog the mind. The brain must be in control, alert, retentive, for it often happens that an accidental stroke of the brush is suggestive, and one should be ever ready to take advantage of the unexpected and profit by experience. In this Preparatory work we have concerned ourselves with primary exercises. Learning how to read in art terms, to spell in its symbols. It is said of Leonardo da Vinci that his dexterity was such that he could draw with both hands at the same time, but though we may not aspire to such cleverness we at least have a sure foundation upon which to build and advance our knowledge.

|

Privacy Policy ...... Contact Us