Home > Directory of Drawing Lesson > Human Face > Drawing Human Heads, Necks, and Shoulders

Drawing People's Heads, Necks, and Shoulders : Learn how to draw the human head, neck muscles, and the shoulders with the following figure drawing and sketching tutorial. |

|

Menu to the Parts of This Article

Drawing Head and Neck - First Lines of Front View

Drawing Head in Profile Side View

Drawing Correct Proportions of Head to Shoulders and Neck

Drawing the Head and Neck of Children

Drawing The Head and Neck : The First Lines of the Front View.

Drawing the Head in Full View with Consideration of the General Form

Drawing the Head in Profile View

The Bones of the Neck

Drawing the Neck Muscles - Sterno-Cleido-Mastoideus

Drawing the Throat

Drawing Subordinate Muscles of the Neck

Drawing the Trapezius Muscle

Proportions of the Neck and Shoulders to the Head

Drawing the Form of the Human Neck

Drawing the Head and Neck of Children

If you Need the Text for the Images Above, You Can Find it Below

The Throat.

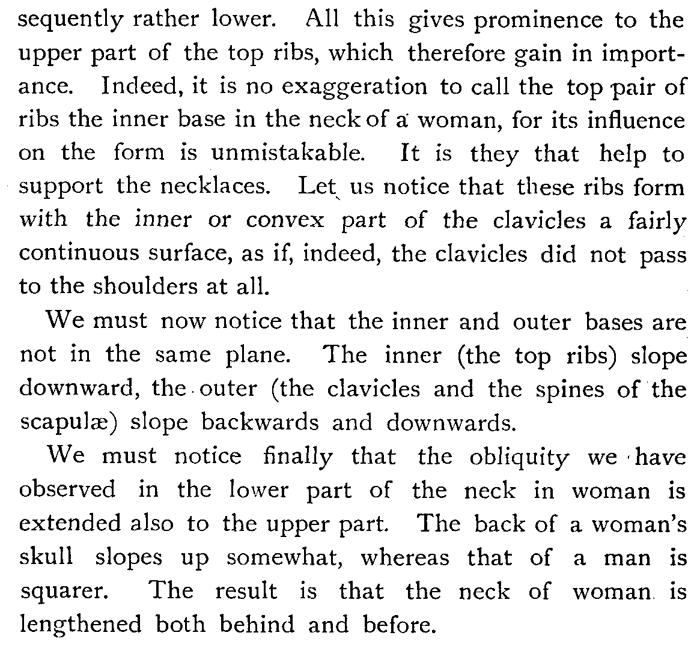

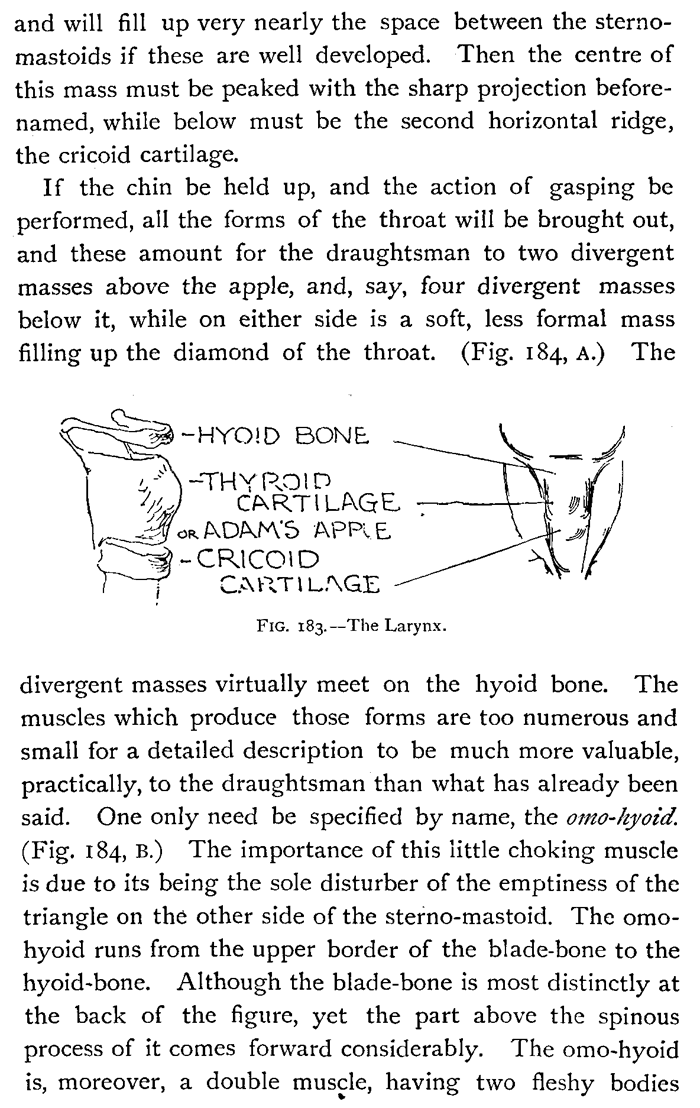

Between the two sterno-mastoids, or bonnet-strings, is the triangular space of the throat. Its apex is at the pit of the neck, its base from angle to angle of the jaw. Another triangle extends from this same base to the chin, and the two together form the space now to be spoken of. At this common base lies the hyoid bone, or U-shaped bone of the tongue, generally omitted from the specimen skeletons to be seen in our schools. It lies fairly horizontally, with the tails of the U directed backwards, and is not too deep but that it may just be felt. This hyoid bone is the uppermost piece of the larynx, the swallowing and vocal apparatus, the other pieces being the thyroid and the cricoid cartilages. It is the thyroid cartilage which forms the mass of the Adam's apple. Upon it occurs a little extra projection coming close up to the skin. The thyroid cartilage is in shape a short piece of a tube, and beneath is the cricoid or ring cartilage, somewhat similar in front to the hyoid bone. These forms are all more distinctly seen in men than in women, for two reasons : first, because they are larger and lower, and second, because they are less masked by the thyroid body, a gland which is not only larger in women but more prominent also, supplying the graceful fullness before a woman's throat. (See Fig. 200.)

In drawing the neck front view, it will be found that the tubular mass, the thyroid cartilage, must first be expressed, and will fill up very nearly the space between the sternomastoids if these are well developed. Then the center of this mass must be peaked with the sharp projection before-named, while below must be the second horizontal ridge, the cricoid cartilage.

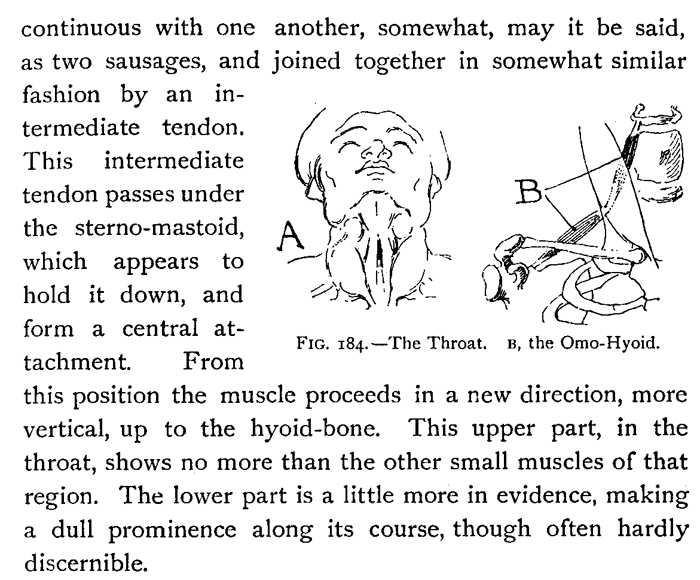

If the chin be held up, and the action of gasping be performed, all the forms of the throat will be brought out, and these amount for the draughtsman to two divergent masses above the apple, and, say, four divergent masses below it, while on either side is a soft, less formal mass filling up the diamond of the throat. (Fig. 184, A.) The divergent masses virtually meet on the hyoid bone. The muscles which produce those forms are too numerous and small for a detailed description to be much more valuable, practically, to the draughtsman than what has already been said. One only need be specified by name, the ono-hyoid. (Fig. 184, B.) The importance of this little choking muscle is due to its being the sole disturber of the emptiness of the triangle on the other side of the sterno-mastoid. The omohyoid runs from the upper border of the blade-bone to the hyoid-bone. Although the blade-bone is most distinctly at the back of the figure, yet the part above the spinous process of it comes forward considerably. The omo-hyoid is, moreover, a double muscle, having two fleshy bodies continuous with one as two sausages, and fashion by an intermediate tendon. This intermediate tendon passes under the sterno-mastoid, which appears to hold it down, and form a central attachment. From this position the muscle proceeds in a new direction, more vertical, up to the hyoid-bone. This upper part, in the throat, shows no more than the other small muscles of that region. The lower part is a little more in evidence, making a dull prominence along its course, though often hardly discernible.

Some Subordinate Muscles of the Neck.

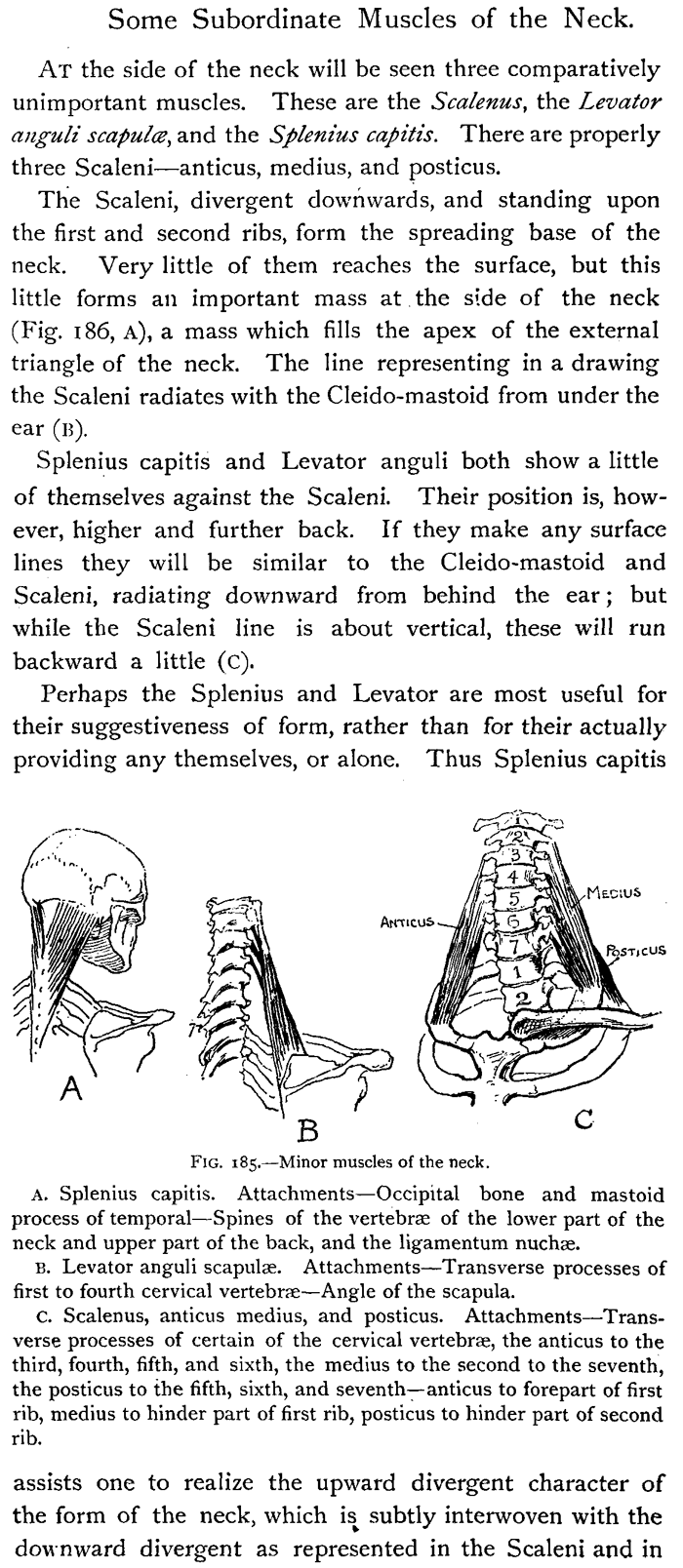

At the side of the neck will be seen three comparatively unimportant muscles. These are the Scalenus, the Levator anguli scapulce, and the Splenius capitis. There are properly three Scaleni—anticus, medius, and posticus.

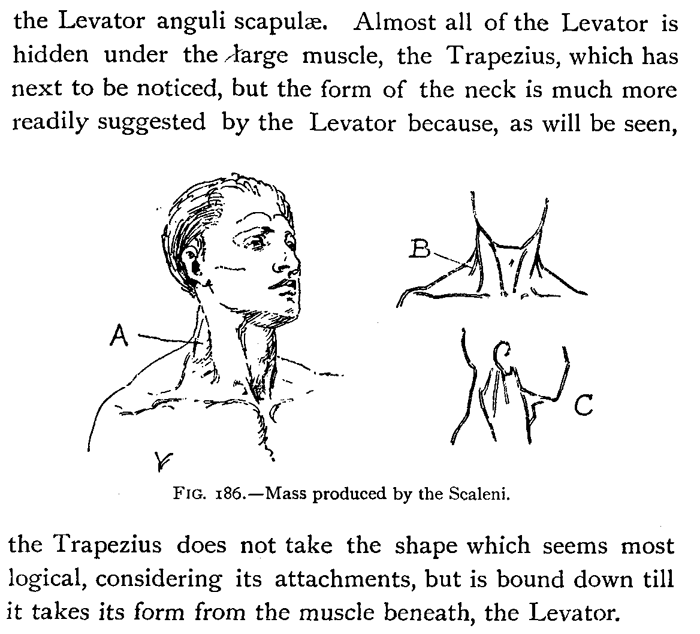

The Scaleni, divergent downwards, and standing upon the first and second ribs, form the spreading base of the neck. Very little of them reaches the surface, but this little forms an important mass at the side of the neck (Fig. 186, A), a mass which fills the apex of the external triangle of the neck. The line representing in a drawing the Scaleni radiates with the Cleido-mastoid from under the ear (B). Splenius capitis and Levator anguli both show a little another, somewhat, may it be said, joined together in somewhat similar of themselves against the Scaleni. Their position is, however, higher and further back. If they make any surface lines they will be similar to the Cleido-mastoid and Scaleni, radiating downward from behind the ear ; but while the Scaleni line is about vertical, these will run backward a little (C).

Perhaps the Splenius and Levator are most useful for their suggestiveness of form, rather than for their actually providing any themselves, or alone. Thus Splenius capitis

A. Splenius capitis. Attachments—Occipital bone and mastoid process of temporal—Spines of the vertebra of the lower part of the neck and upper part of the back, and the ligamentum nucha.

B. Levator anguli scapula. Attachments—Transverse processes of first to fourth cervical vertebra—Angle of the scapula.

C. Scalenus, anticus medius, and posticus. Attachments—Transverse processes of certain of the cervical vertebra, the anticus to the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth, the medius to the second to the seventh, the posticus to the fifth, sixth, and seventh—anticus to forepart of first rib, medius to hinder part of first rib, posticus to hinder part of second rib. assists one to realize the upward divergent character of the form of the neck, which is. subtly interwoven with the downward divergent as represented in the Scaleni and in the Levator anguli scapulae. Almost all of the Levator is hidden under the -large muscle, the Trapezius, which has next to be noticed, but the form of the neck is much more readily suggested by the Levator because, as will be seen, the Trapezius does not take the shape which seems most logical, considering its attachments, but is bound down till it takes its form from the muscle beneath, the Levator.

The Trapezius Muscle.

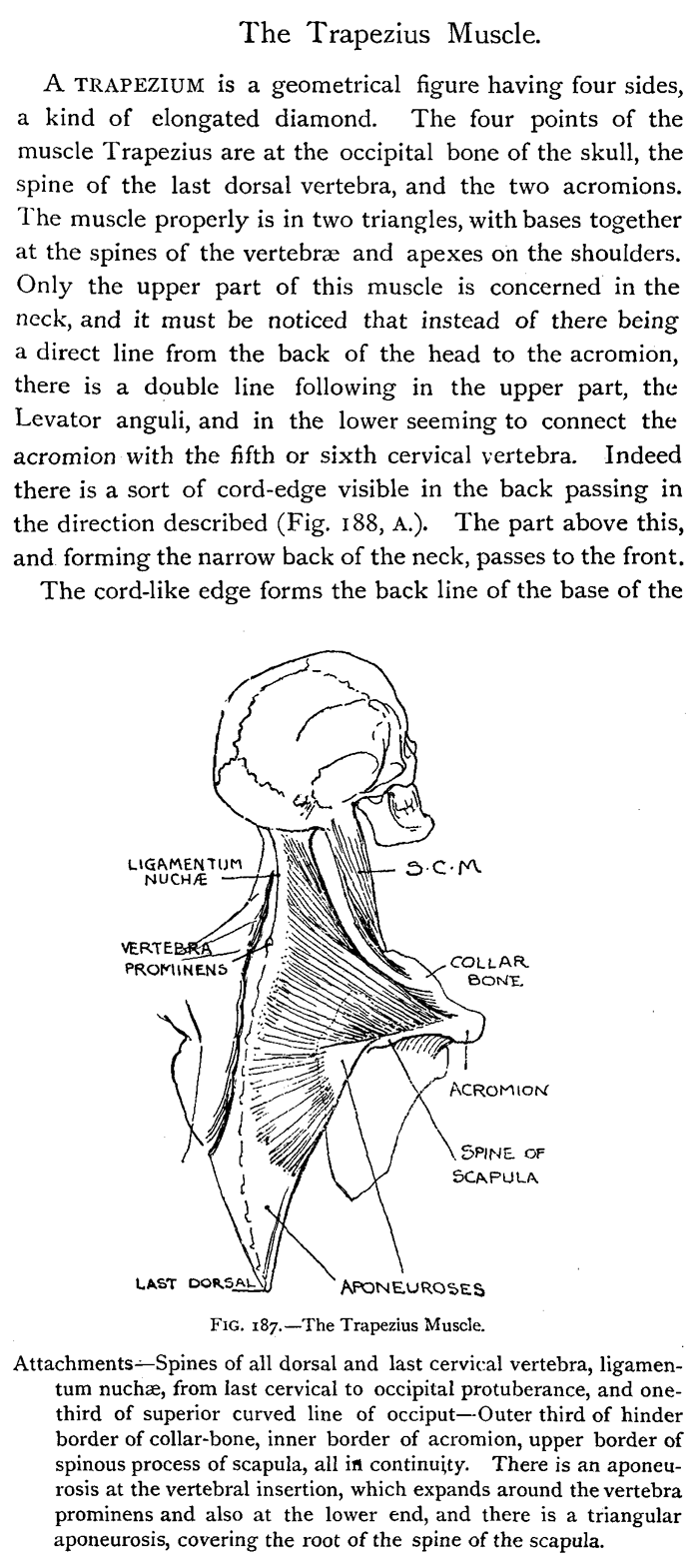

A Trapezium is a geometrical figure having four sides, a kind of elongated diamond. The four points of the muscle Trapezius are at the occipital bone of the skull, the spine of the last dorsal vertebra, and the two acromions. The muscle properly is in two triangles, with bases together at the spines of the vertebre and apexes on the shoulders. Only the upper part of this muscle is concerned in the neck, and it must be noticed that instead of there being a direct line from the back of the head to the acromion, there is a double line following in the upper part, the Levator anguli, and in the lower seeming to connect the

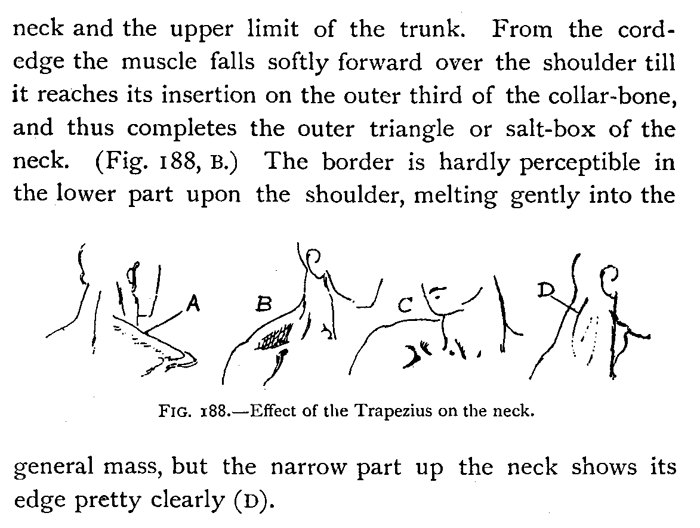

acromion with the fifth or sixth cervical vertebra. Indeed there is a sort of cord-edge visible in the back passing in the direction described (Fig. 188, A.). The part above this, and forming the narrow back of the neck, passes to the front.

The cord-like edge forms the back line of the base of the

neck and the upper limit of the trunk. From the cord-edge the muscle falls softly forward over the shoulder till it reaches its insertion on the outer third of the collar-bone, and thus completes the outer triangle or salt-box of the neck. (Fig. 188, B.) The border is hardly perceptible in the lower part upon the shoulder, melting gently into the

general mass, but the narrow part up the neck shows its edge pretty clearly (D).

Proportions of the Neck and Shoulders to the Head.

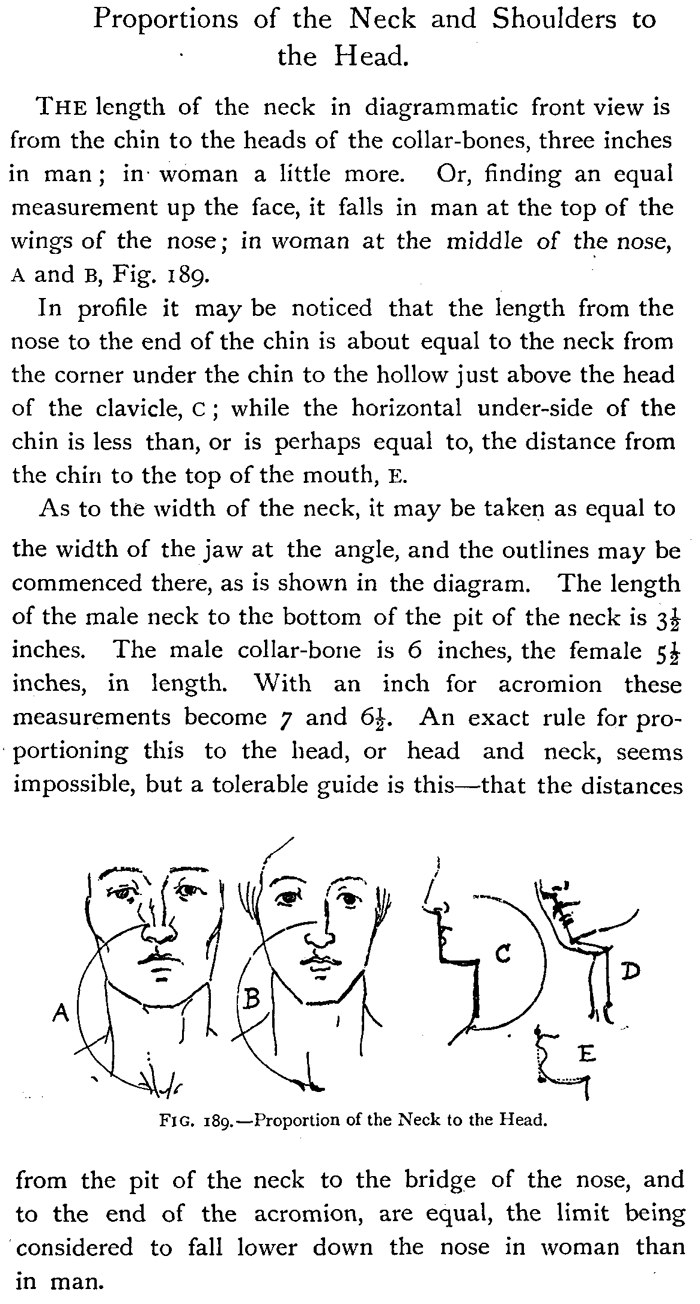

The length of the neck in diagrammatic front view is from the chin to the heads of the collar-bones, three inches in man ; in woman a little more. Or, finding an equal measurement up the face, it falls in man at the top of the wings of the nose; in woman at the middle of the nose, A and B, Fig. 189.

In profile it may be noticed that the length from the nose to the end of the chin is about equal to the neck from the corner under the chin to the hollow just above the head of the clavicle, c ; while the horizontal under-side of the chin is less than, or is perhaps equal to, the distance from the chin to the top of the mouth, E.

As to the width of the neck, it may be taken as equal to the width of the jaw at the angle, and the outlines may be commenced there, as is shown in the diagram. The length of the male neck to the bottom of the pit of the neck is 3i inches. The male collar-bone is 6 inches, the female 5i inches, in length. With an inch for acromion these measurements become 7 and 6. An exact rule for proportioning this to the head, or head and neck, seems impossible, but a tolerable guide is this—that the distances

from the pit of the neck to the bridge of the nose, and to the end of the acromion, are equal, the limit being considered to fall lower down the nose in woman than in man.

The Form of the Neck.

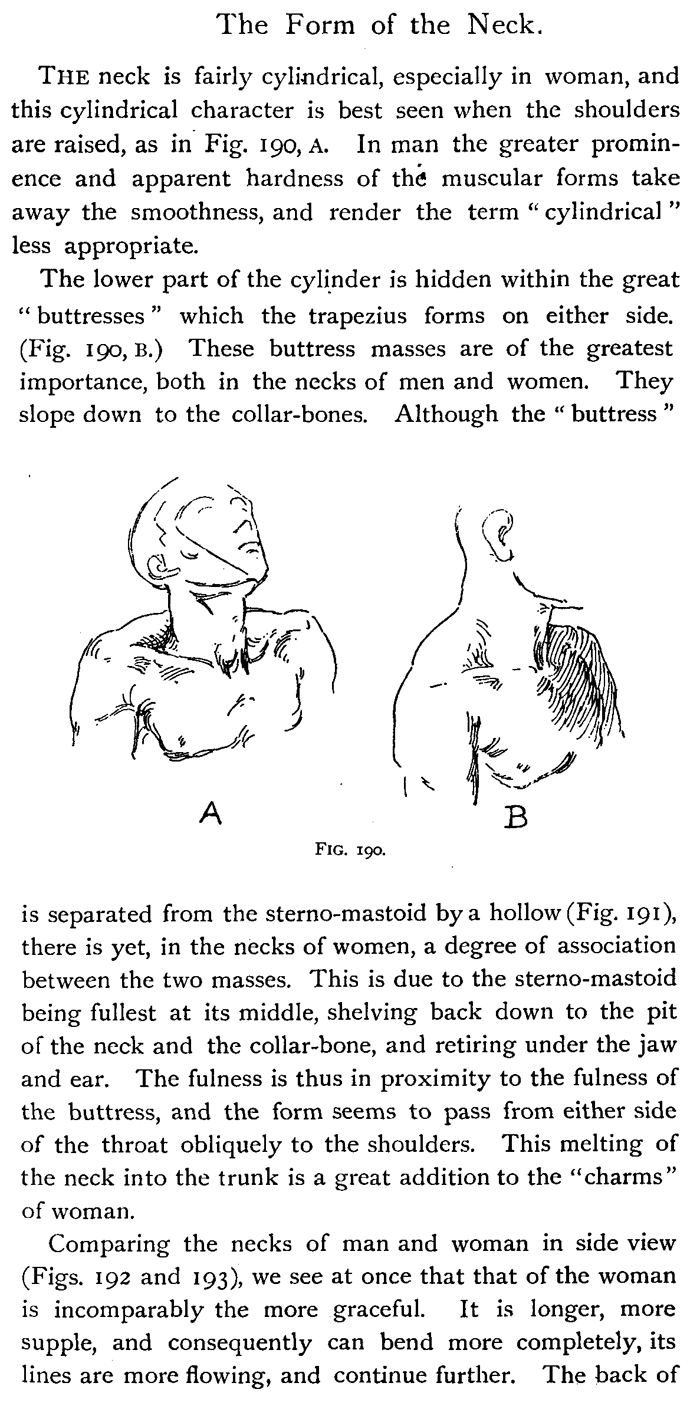

The neck is fairly cylindrical, especially in woman, and this cylindrical character is best seen when the shoulders are raised, as in Fig. 19o, A. In man the greater prominence and apparent hardness of the muscular forms take away the smoothness, and render the term " cylindrical " less appropriate.

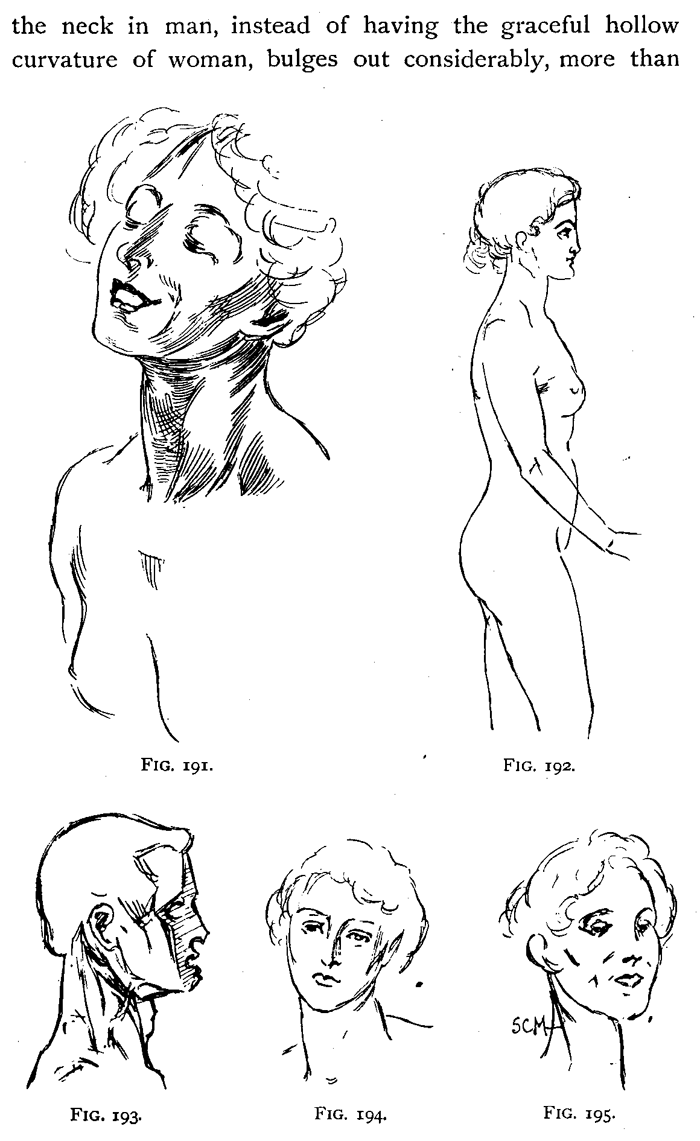

The lower part of the cylinder is hidden within the great " buttresses " which the trapezius forms on either side. (Fig. 19o, B.) These buttress masses are of the greatest importance, both in the necks of men and women. They slope down to the collar-bones. Although the " buttress " is separated from the sterno-mastoid by a hollow (Fig. 191), there is yet, in the necks of women, a degree of association between the two masses. This is due to the sterno-mastoid being fullest at its middle, shelving back down to the pit of the neck and the collar-bone, and retiring under the jaw and ear. The fullness is thus in proximity to the fullness of the buttress, and the form seems to pass from either side of the throat obliquely to the shoulders. This melting of the neck into the trunk is a great addition to the "charms" of woman.

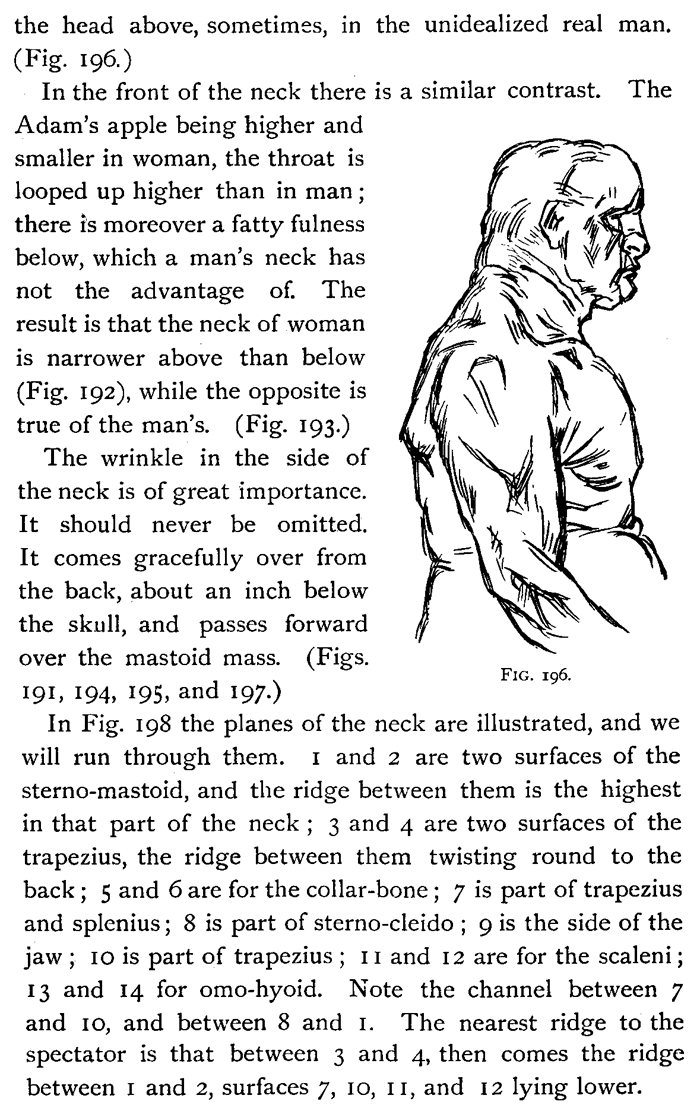

Comparing the necks of man and woman in side view (Figs. 192 and 193), we see at once that that of the woman is incomparably the more graceful. It is longer, more supple, and consequently can bend more completely, its lines are more flowing, and continue further. The back of the neck in man, instead of having the graceful hollow curvature of woman, bulges out considerably, more than the head above, sometimes, in the un-idealized real man. (Fig. 196.)

In the front of the neck there is a similar contrast. The Adam's apple being higher and smaller in woman, the throat is looped up higher than in man ; there is moreover a fatty fullness below, which a man's neck has not the advantage of. The result is that the neck of woman is narrower above than below (Fig. 192), while the opposite is true of the man's. (Fig. 193.)

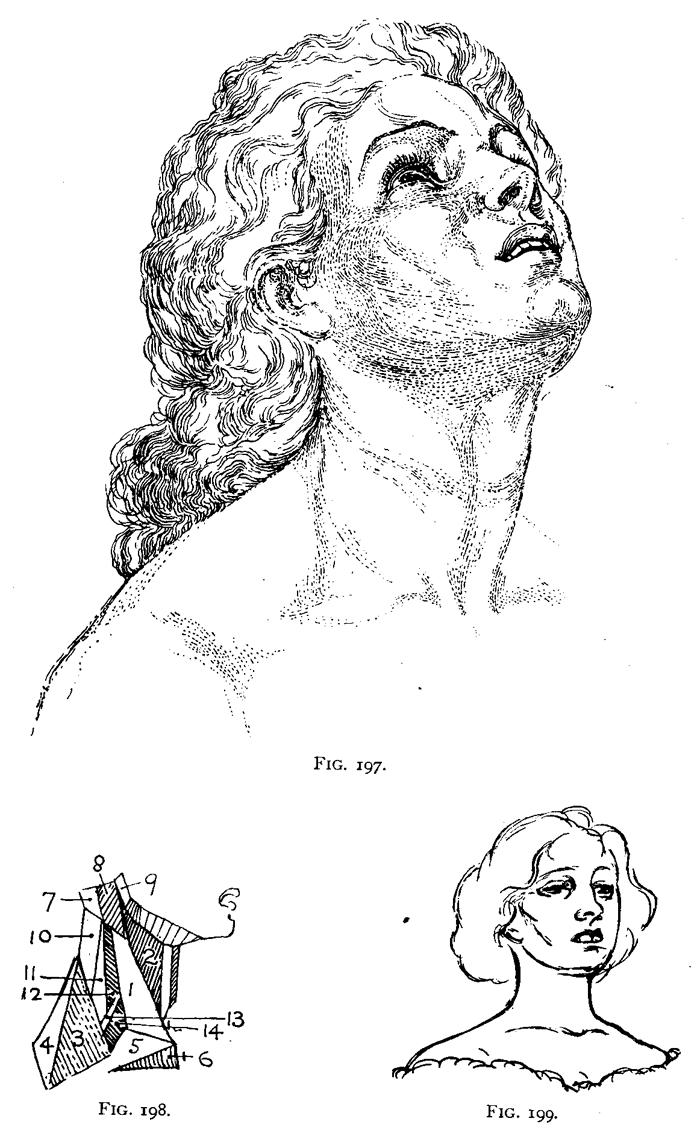

The wrinkle in the side of the neck is of great importance. It should never be omitted. It comes gracefully over from the back, about an inch below the skull, and passes forward over the mastoid mass. (Figs. 191, 194, 195, and 197.)

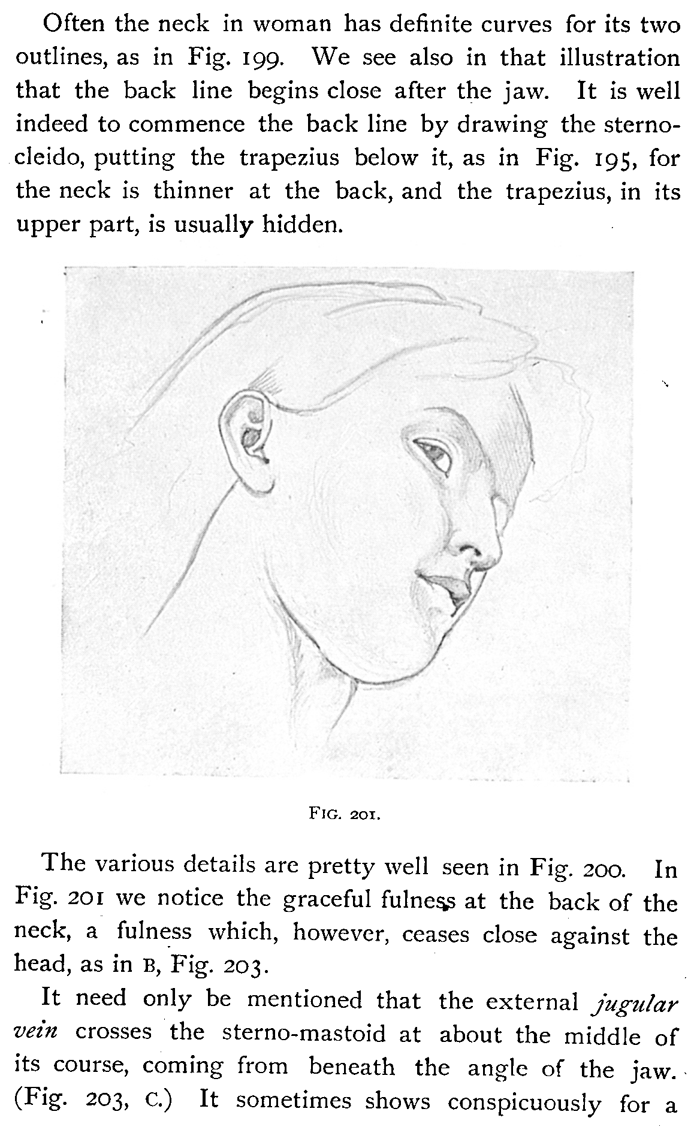

In Fig. 198 the planes of the neck are illustrated, and we will run through them. 1 and 2 are two surfaces of the sterno-mastoid, and the ridge between them is the highest in that part of the neck ; 3 and 4 are two surfaces of the trapezius, the ridge between them twisting round to the back ; 5 and 6 are for the collar-bone ; 7 is part of trapezius and splenius ; 8 is part of sterno-cleido ; 9 is the side of the jaw ; 10 is part of trapezius ; 11 and 12 are for the scaleni ; 13 and 14 for omo-hyoid. Note the channel between 7 and 10, and between 8 and 1. The nearest ridge to the spectator is that between 3 and 4, then comes the ridge between 1 and 2, surfaces 7, 10, 11, and 12 lying lower.

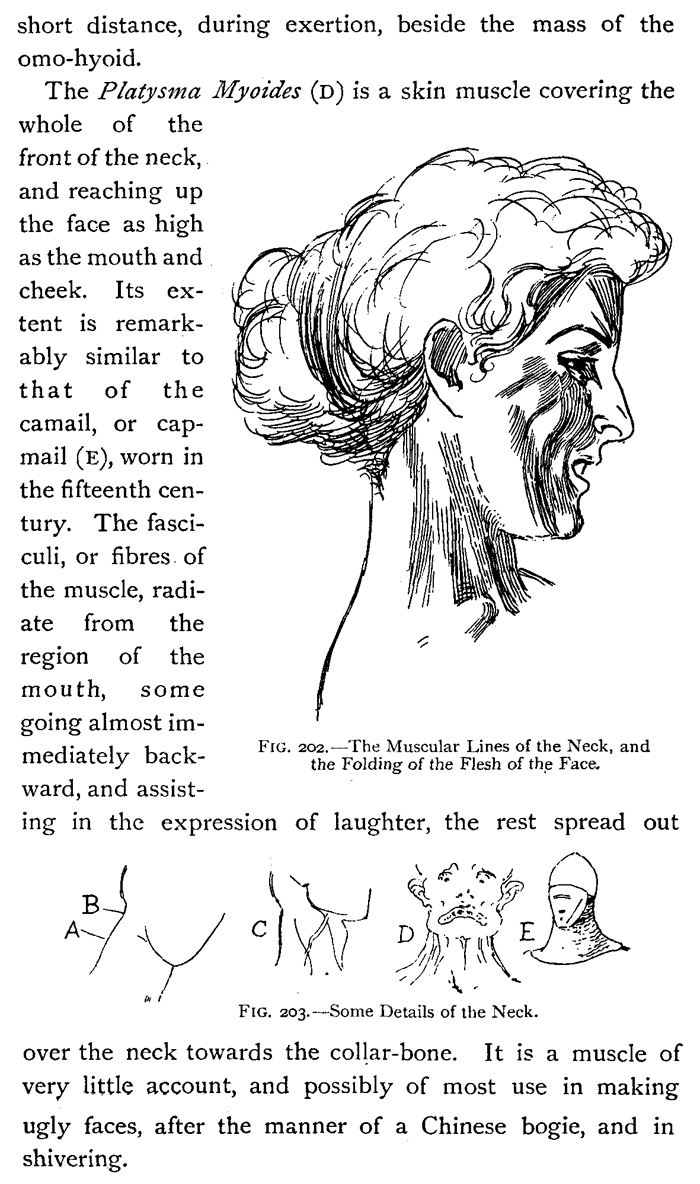

Often the neck in woman has definite curves for its two outlines, as in Fig. 199. We see also in that illustration that the back line begins close after the jaw. It is well indeed to commence the back line by drawing the sternocleido, putting the trapezius below it, as in Fig. 195, for the neck is thinner at the back, and the trapezius, in its upper part, is usually hidden.

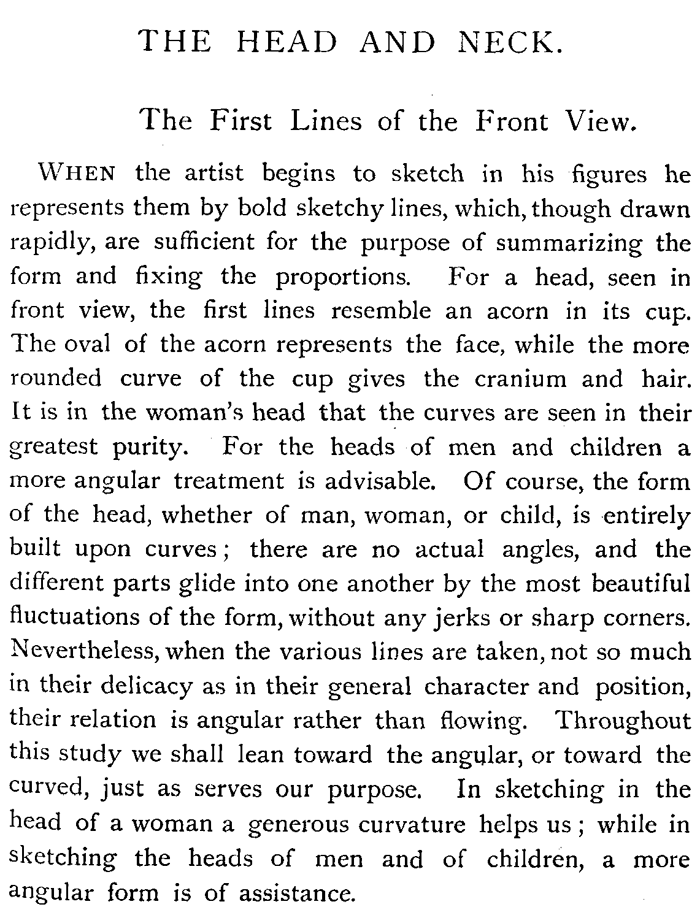

The various details are pretty well seen in Fig. 200. In Fig. 201 we notice the graceful fullness at the back of the neck, a fullness which, however, ceases close against the head, as in B, Fig. 203.

It need only be mentioned that the external jugular vein crosses the sterno-mastoid at about the middle of its course, coming from beneath the angle of the jaw. (Fig. 203, C.) It sometimes shows conspicuously for a short distance, during exertion, beside the mass of the omo-hyoid.

The Platysma Myoides (D) is a skin muscle covering the whole of the front of the neck, and reaching up the face as high as the mouth and cheek. Its extent is remarkably similar to that of the camail, or cap-mail (E), worn in the fifteenth century. The fasciculi, or fibres of the muscle, radiate from the region of the mouth, some going almost immediately backward, and assisting in the expression of laughter, the rest spread out over the neck towards the collar-bone. It is a muscle of very little account, and possibly of most use in making ugly faces, after the manner of a Chinese bogie, and in shivering.

Drawing the Head and Neck : The First Lines of the Front View

When the artist begins to sketch in his figures he represents them by bold sketchy lines, which, though drawn rapidly, are sufficient for the purpose of summarizing the form and fixing the proportions. For a head, seen in front view, the first lines resemble an acorn in its cup. The oval of the acorn represents the face, while the more rounded curve of the cup gives the cranium and hair. It is in the woman's head that the curves are seen in their greatest purity. For the heads of men and children a more angular treatment is advisable. Of course, the form of the head, whether of man, woman, or child, is entirely built upon curves ; there are no actual angles, and the different parts glide into one another by the most beautiful fluctuations of the form, without any jerks or sharp corners. Nevertheless, when the various lines are taken, not so much in their delicacy as in their general character and position, their relation is angular rather than flowing. Throughout this study we shall lean toward the angular, or toward the curved, just as serves our purpose. In sketching in the head of a woman a generous curvature helps us ; while in sketching the heads of men and of children, a more angular form is of assistance.

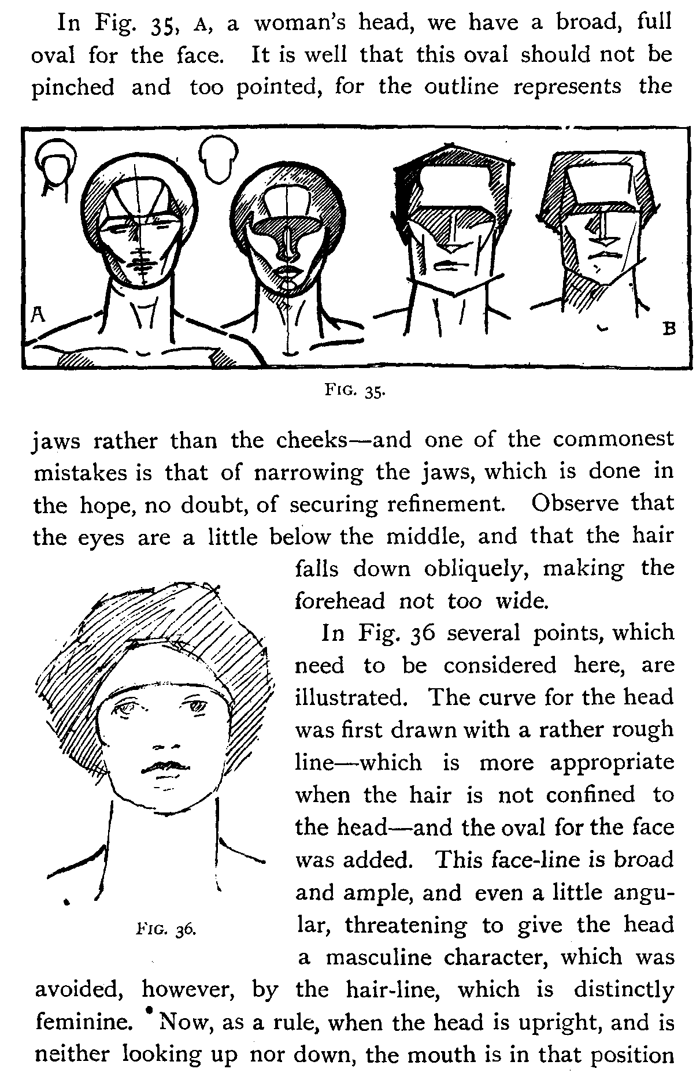

In Fig. 35, A, a woman's head, we have a broad, full oval for the face. It is well that this oval should not be pinched and too pointed, for the outline represents the jaws rather than the cheeks—and one of the commonest mistakes is that of narrowing the jaws, which is done in the hope, no doubt, of securing refinement. Observe that the eyes are a little below the middle, and that the hair falls down obliquely, making the forehead not too wide.

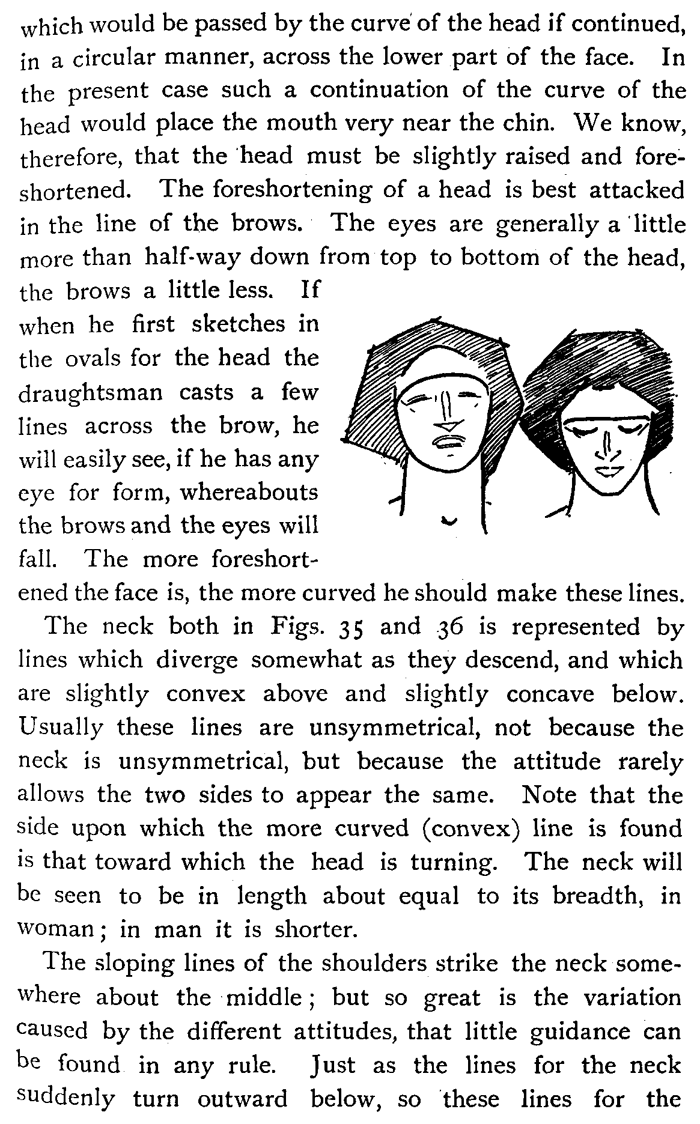

In Fig. 36 several points, which need to be considered here, are illustrated. The curve for the head was first drawn with a rather rough line—which is more appropriate when the hair is not confined to the head—and the oval for the face was added. This face-line is broad

and ample, and even a little angular, threatening to give the head a masculine character, which was avoided, however, by the hair-line, which is distinctly feminine. Now, as a rule, when the head is upright, and is neither looking up nor down, the mouth is in that position which would be passed by the curve of the head if continued, in a circular manner, across the lower part of the face. In the present case such a continuation of the curve of the head would place the mouth very near the chin. We know, therefore, that the head must be slightly raised and foreshortened. The foreshortening of a head is best attacked in the line of the brows. The eyes are generally a little more than half-way down from top to bottom of the head, the brows a little less. If

when he first sketches in the ovals for the head the draughtsman casts a few lines across the brow, he will easily see, if he has any eye for form, whereabouts the brows and the eyes will fall. The more foreshortened the face is, the more curved he should make these lines.

The neck both in Figs. 35 and 36 is represented by lines which diverge somewhat as they descend, and which are slightly convex above and slightly concave below. Usually these lines are unsymmetrical, not because the neck is unsymmetrical, but because the attitude rarely allows the two sides to appear the same. Note that the side upon which the more curved (convex) line is found is that toward which the head is turning. The neck will be seen to be in length about equal to its breadth, in woman ; in man it is shorter.

The sloping lines of the shoulders strike the neck somewhere about the middle ; but so great is the variation caused by the different attitudes, that little guidance can be found in any rule. Just as the lines for the neck suddenly turn outward below, so these lines for the shoulders as suddenly turn upward as they meet the neck. (Fig. 36.)

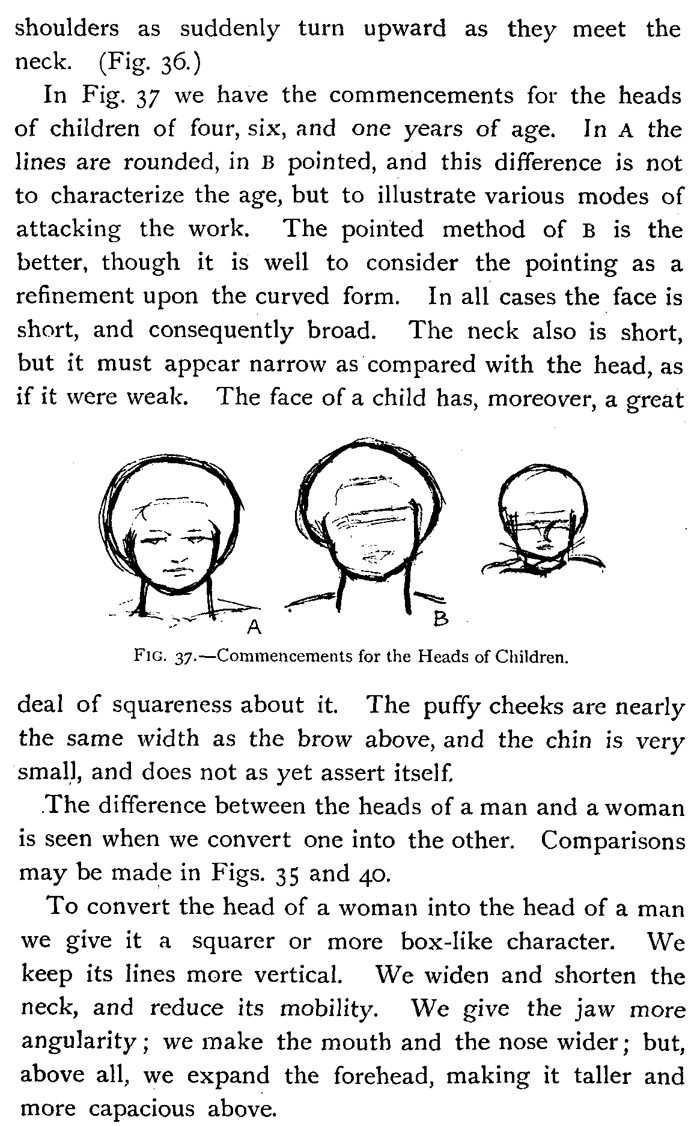

In Fig. 37 we have the commencements for the heads of children of four, six, and one years of age. In A the lines are rounded, in B pointed, and this difference is not to characterize the age, but to illustrate various modes of attacking the work. The pointed method of B is the better, though it is well to consider the pointing as a refinement upon the curved form. In all cases the face is short, and consequently broad. The neck also is short, but it must appear narrow as compared with the head, as if it were weak. The face of a child has, moreover, a great deal of squareness about it. The puffy cheeks are nearly the same width as the brow above, and the chin is very small, and does not as yet assert itself.

The difference between the heads of a man and a woman is seen when we convert one into the other. Comparisons may be made in Figs. 35 and 40.

To convert the head of a woman into the head of a man we give it a squarer or more box-like character. We keep its lines more vertical. We widen and shorten the neck, and reduce its mobility. We give the jaw more angularity ; we make the mouth and the nose wider; but, above all, we expand the forehead, making it taller and more capacious above.

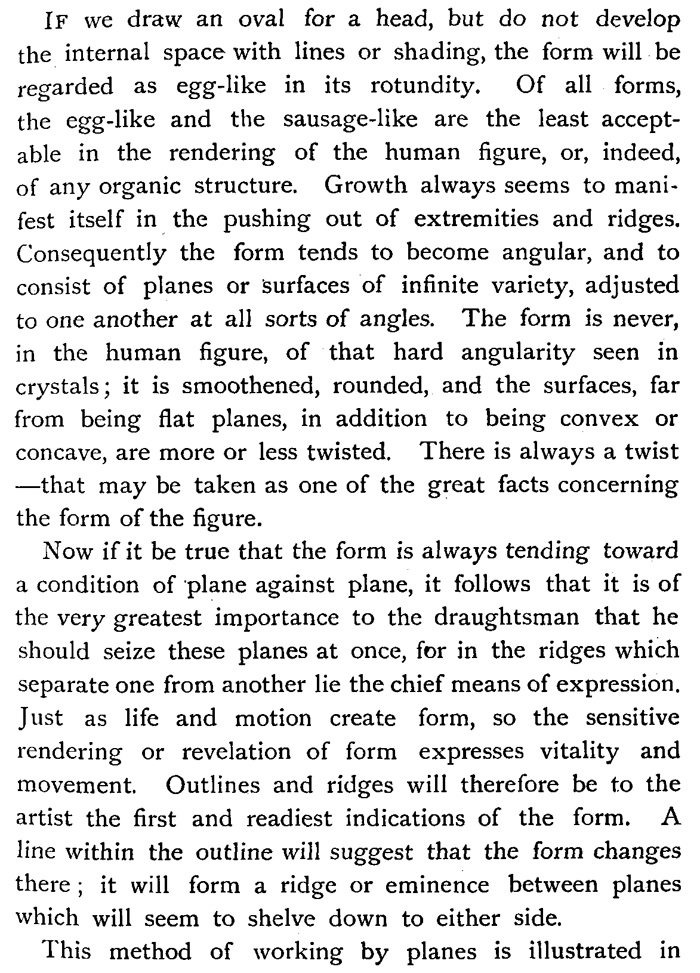

If we draw an oval for a head, but do not develop the internal space with lines or shading, the form will be regarded as egg-like in its rotundity. Of all forms, the egg-like and the sausage-like are the least acceptable in the rendering of the human figure, or, indeed, of any organic structure. Growth always seems to manifest itself in the pushing out of extremities and ridges. Consequently the form tends to become angular, and to consist of planes or surfaces of infinite variety, adjusted to one another at all sorts of angles. The form is never, in the human figure, of that hard angularity seen in crystals ; it is smoothened, rounded, and the surfaces, far from being flat planes, in addition to being convex or concave, are more or less twisted. There is always a twist —that may be taken as one of the great facts concerning the form of the figure.

Now if it be true that the form is always tending toward a condition of plane against plane, it follows that it is of the very greatest importance to the draughtsman that he should seize these planes at once, for in the ridges which separate one from another lie the chief means of expression. Just as life and motion create form, so the sensitive rendering or revelation of form expresses vitality and movement. Outlines and ridges will therefore be to the artist the first and readiest indications of the form. A line within the outline will suggest that the form changes there ; it will form a ridge or eminence between planes which will seem to shelve down to either side.

This method of working by planes is illustrated in

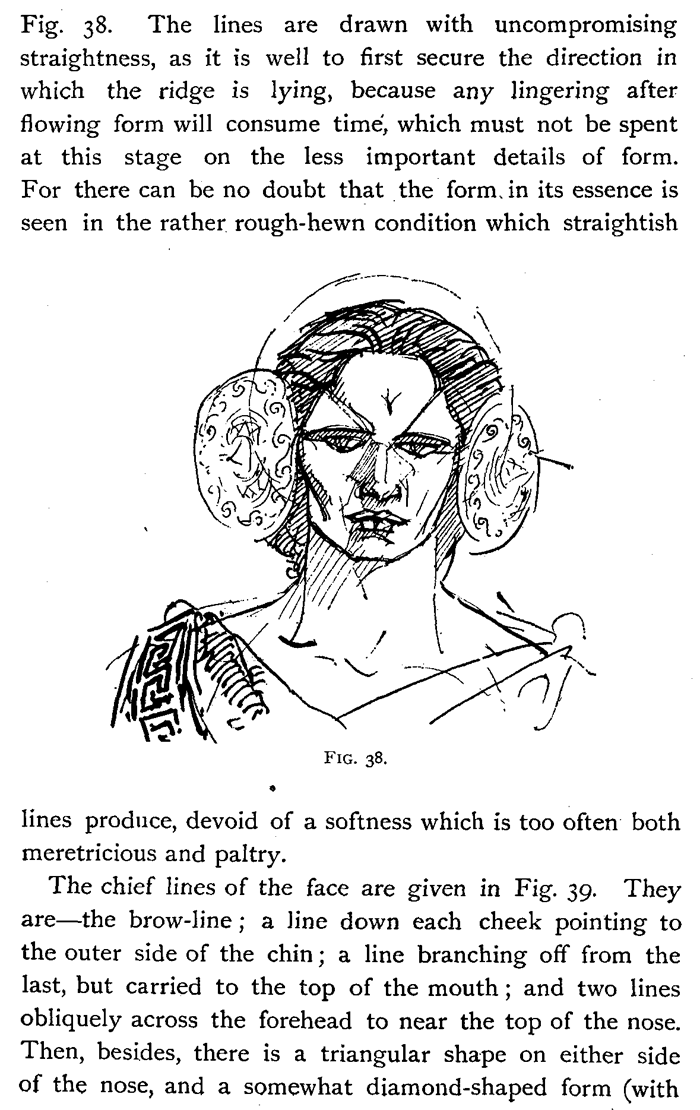

Fig. 38. The lines are drawn with uncompromising straightness, as it is well to first secure the direction in which the ridge is lying, because any lingering after flowing form will consume time, which must not be spent at this stage on the less important details of form. For there can be no doubt that the form, in its essence is seen in the rather rough-hewn condition which straightish

lines produce, devoid of a softness which is too often both meretricious and paltry.

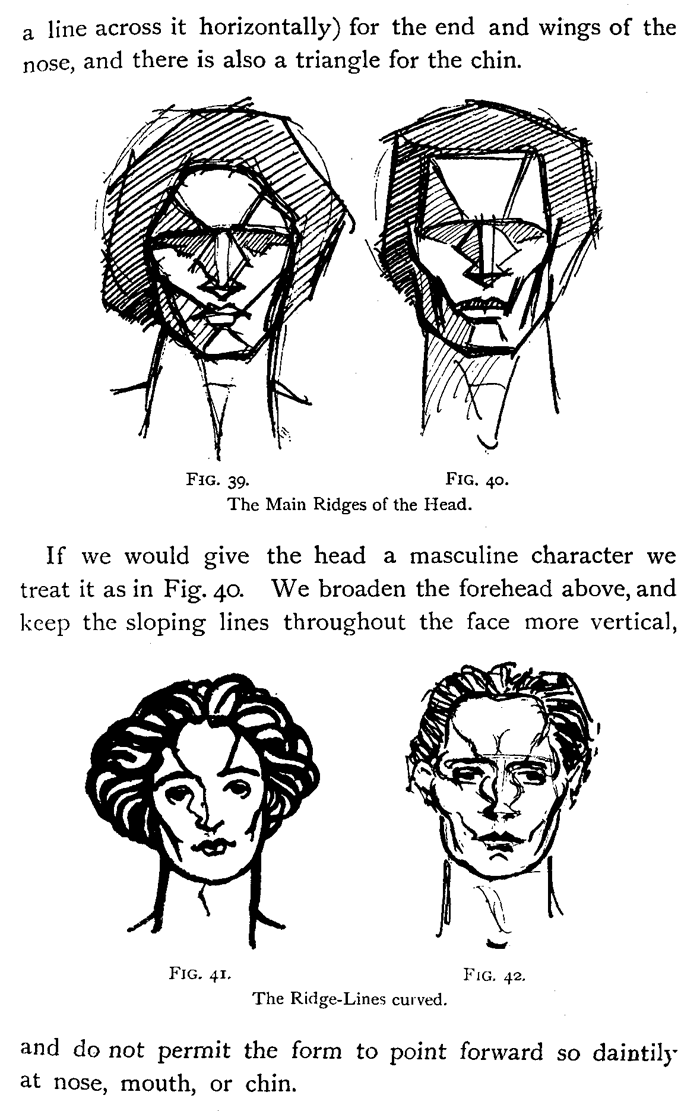

The chief lines of the face are given in Fig. 39. They are—the brow-line ; a line down each cheek pointing to the outer side of the chin ; a line branching off from the last, but carried to the top of the mouth ; and two lines obliquely across the forehead to near the top of the nose. Then, besides, there is a triangular shape on either side of the nose, and a somewhat diamond-shaped form (with

a line across it horizontally) for the end and wings of the nose, and there is also a triangle for the chin.

If we would give the head a masculine character we treat it as in Fig. 40. We broaden the forehead above, and keep the sloping lines throughout the face more vertical, and do not permit the form to point forward so daintily at nose, mouth, or chin.

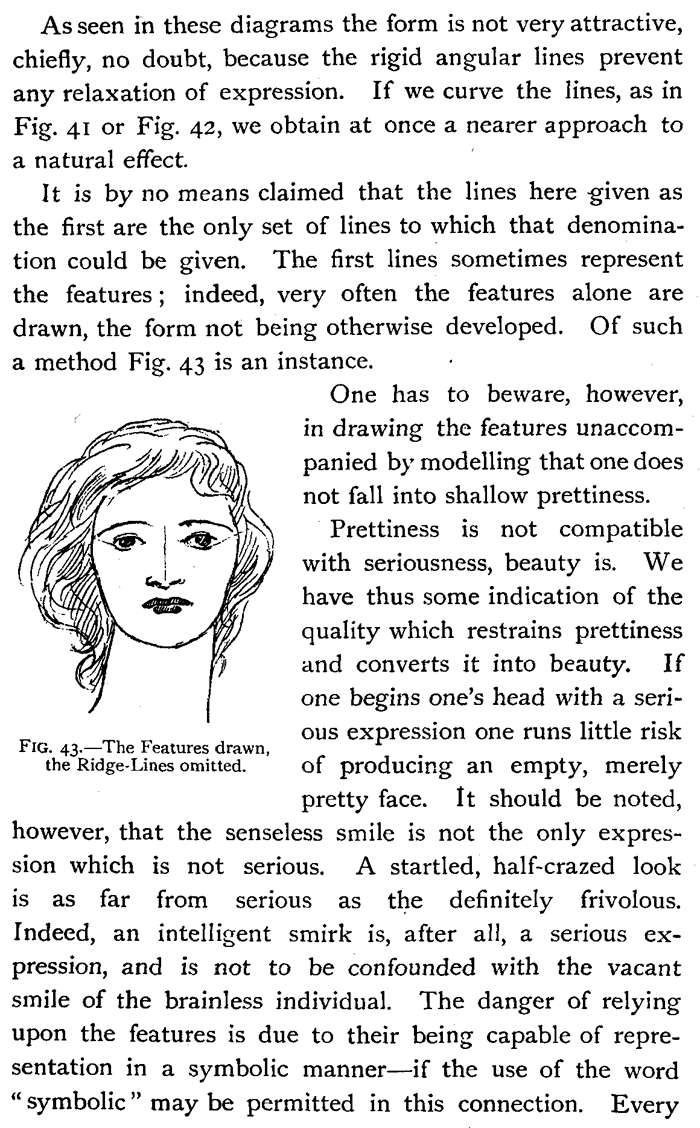

As seen in these diagrams the form is not very attractive, chiefly, no doubt, because the rigid angular lines prevent any relaxation of expression. If we curve the lines, as in Fig. 41 or Fig. 42, we obtain at once a nearer approach to a natural effect.

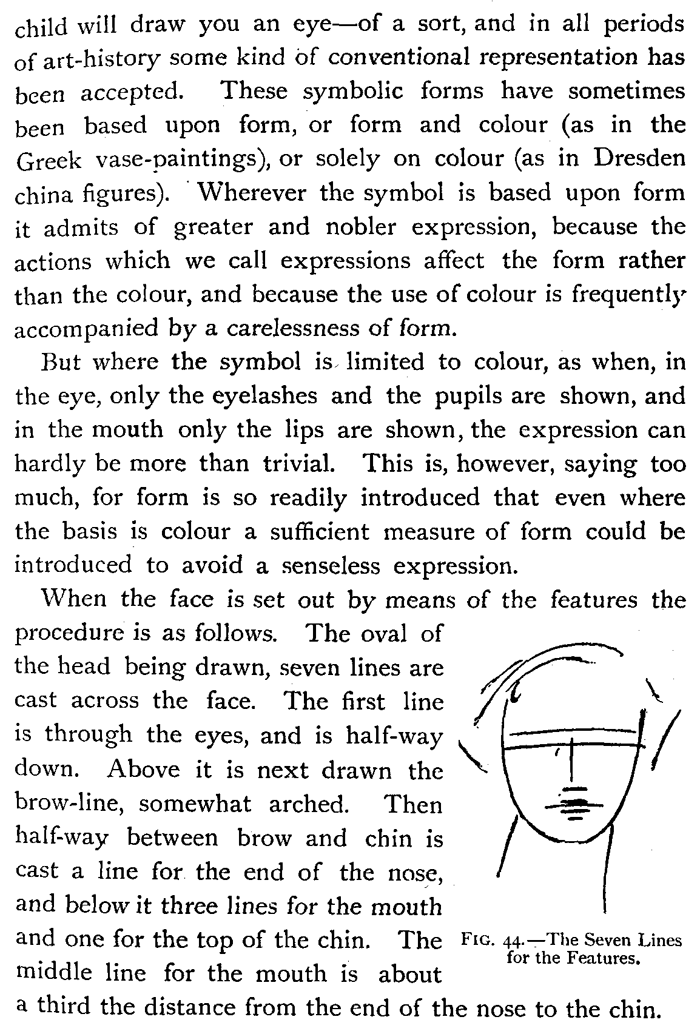

It is by no means claimed that the lines here given as the first are the only set of lines to which that denomination could be given. The first lines sometimes represent the features ; indeed, very often the features alone are drawn, the form not being otherwise developed. Of such a method Fig. 43 is an instance.

One has to beware, however, in drawing the features unaccompanied by modeling that one does not fall into shallow prettiness. Prettiness is not compatible with seriousness, beauty is. We have thus some indication of the quality which restrains prettiness

and converts it into beauty. If one begins one's head with a serious expression one runs little risk of producing an empty, merely pretty face. It should be noted, however, that the senseless smile is not the only expression which is not serious. A startled, half-crazed look is as far from serious as the definitely frivolous. Indeed, an intelligent smirk is, after all, a serious expression, and is not to be confounded with the vacant smile of the brainless individual. The danger of relying upon the features is due to their being capable of representation in a symbolic manner—if the use of the word "symbolic" may be permitted in this connection. Every child will draw you an eye—of a sort, and in all periods of art-history some kind of conventional representation has been accepted. These symbolic forms have sometimes been based upon form, or form and color (as in the Greek vase-paintings), or solely on color (as in Dresden china figures). Wherever the symbol is based upon form it admits of greater and nobler expression, because the actions which we call expressions affect the form rather than the color, and because the use of color is frequently accompanied by a carelessness of form.

But where the symbol is limited to color, as when, in the eye, only the eyelashes and the pupils are shown, and in the mouth only the lips are shown, the expression can hardly be more than trivial. This is, however, saying too much, for form is so readily introduced that even where the basis is color a sufficient measure of form could be introduced to avoid a senseless expression.

When the face is set out by means of the features the procedure is as follows. The oval of the head being drawn, seven lines are cast across the face. The first line is through the eyes, and is half-way down. Above it is next drawn the brow-line, somewhat arched. Then half-way between brow and chin is cast a line for the end of the nose, and below it three lines for the mouth and one for the top of the chin. The FIG. 44.—The Seven Lines middle line for the mouth is about a third the distance from the end of the nose to the chin.

Drawing The Head in Full View as well as Further Consideration of the General Form.

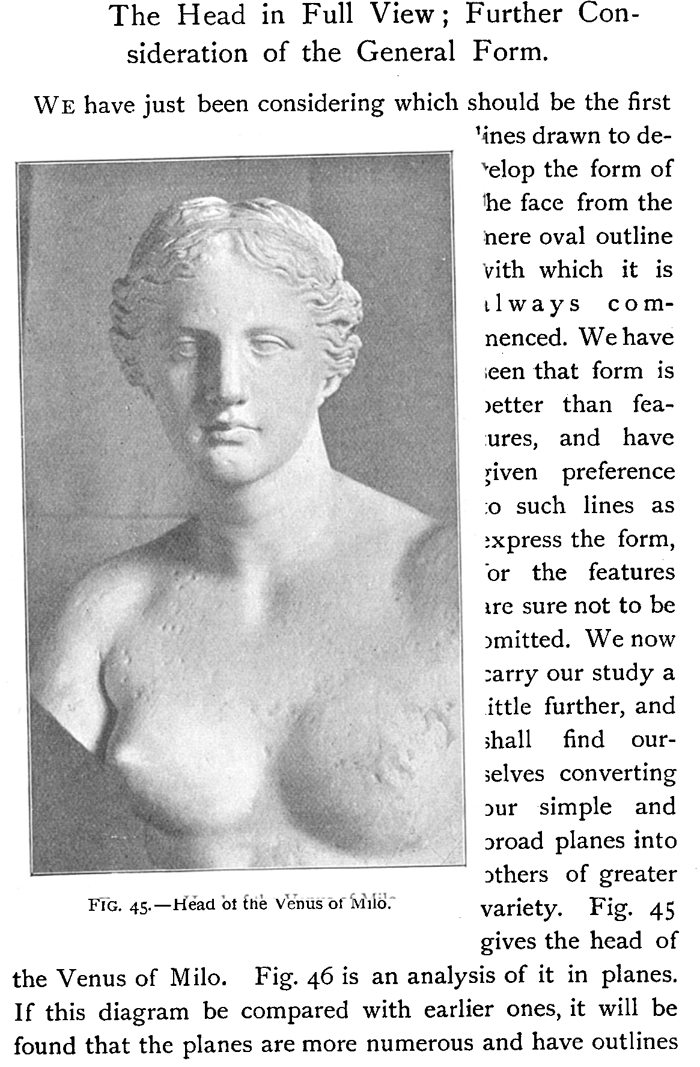

We have just been considering which should be the first lines drawn to develop the form of the face from the mere oval outline. We have seen that form is better than features, and have driven preference to such lines as express the form, or the features

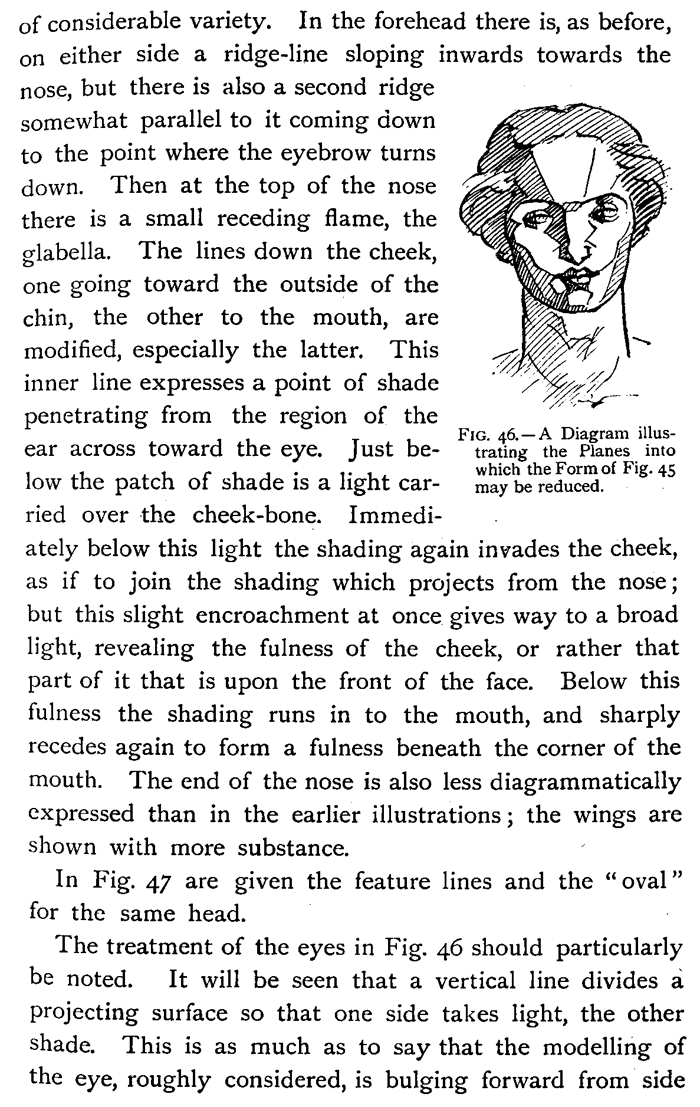

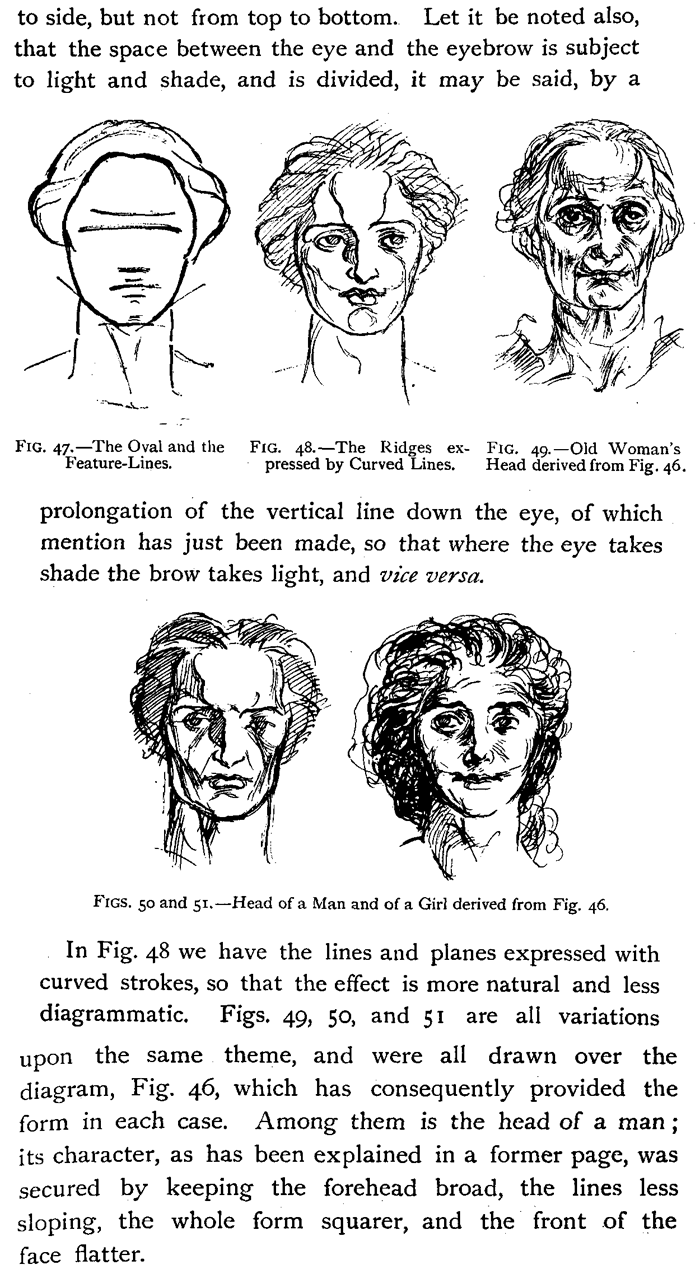

are sure not to be omitted. We now carry our study a little further, and shall find ourselves converting cur simple and broad planes into others of greater variety. If this diagram be compared with earlier ones, it will be found that the planes are more numerous and have outlines of considerable variety. In the forehead there is, as before, on either side a ridge-line sloping inwards towards the nose, but there is also a second ridge somewhat parallel to it coming down to the point where the eyebrow turns down. Then at the top of the nose there is a small receding flame, the glabella. The lines down the cheek, one going toward the outside of the chin, the other to the mouth, are modified, especially the latter. This ear across toward the eye. Just be- trating the Planes into which the Form of Fig. 45 low the patch of shade is a light car- may be reduced. dried over the cheek-bone. Immediately below this light the shading again invades the cheek, as if to join the shading which projects from the nose ; but this slight encroachment at once gives way to a broad light, revealing the fullness of the cheek, or rather that part of it that is upon the front of the face. Below this fullness the shading runs in to the mouth, and sharply recedes again to form a fullness beneath the corner of the mouth. The end of the nose is also less diagrammatically expressed than in the earlier illustrations ; the wings are shown with more substance.

In Fig. 47 are given the feature lines and the " oval " for the same head. The treatment of the eyes in Fig. 46 should particularly be noted. It will be seen that a vertical line divides a projecting surface so that one side takes light, the other shade. This is as much as to say that the modeling of the eye, roughly considered, is bulging forward from side inner line expresses a point of shade penetrating from the region of the to side, but not from top to bottom. Let it be noted also, that the space between the eye and the eyebrow is subject to light and shade, and is divided, it may be said, by a prolongation of the vertical line down the eye, of which mention has just been made, so that where the eye takes shade the brow takes light, and vice versa.

In Fig. 48 we have the lines and planes expressed with curved strokes, so that the effect is more natural and less diagrammatic. Figs. 49, 5o, and 51 are all variations upon the same theme, and were all drawn over the diagram, Fig. 46, which has consequently provided the form in each case. Among them is the head of a man ; its character, as has been explained in a former page, was secured by keeping the forehead broad, the lines less sloping, the whole form squarer, and the front of the face flatter.

The Head in Profile.

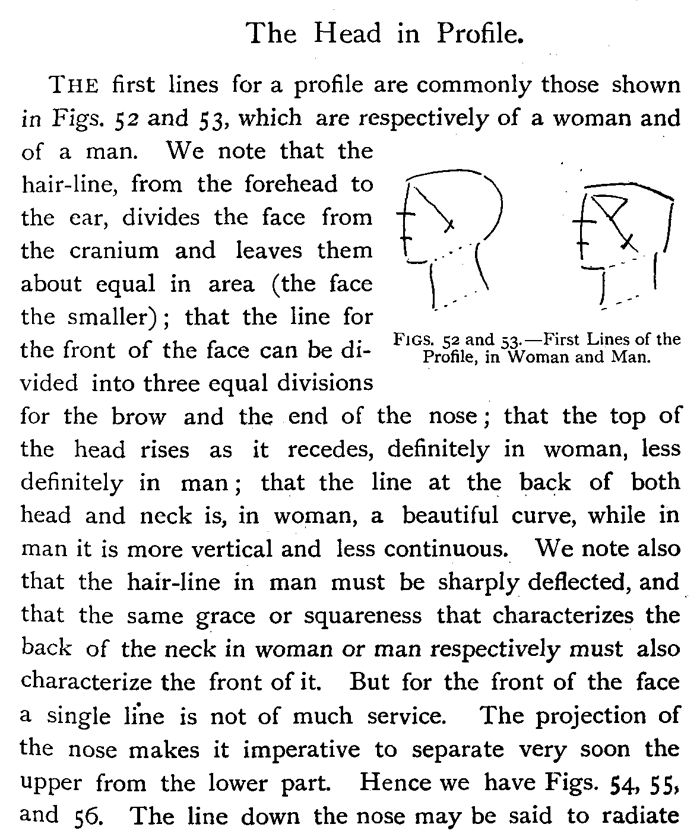

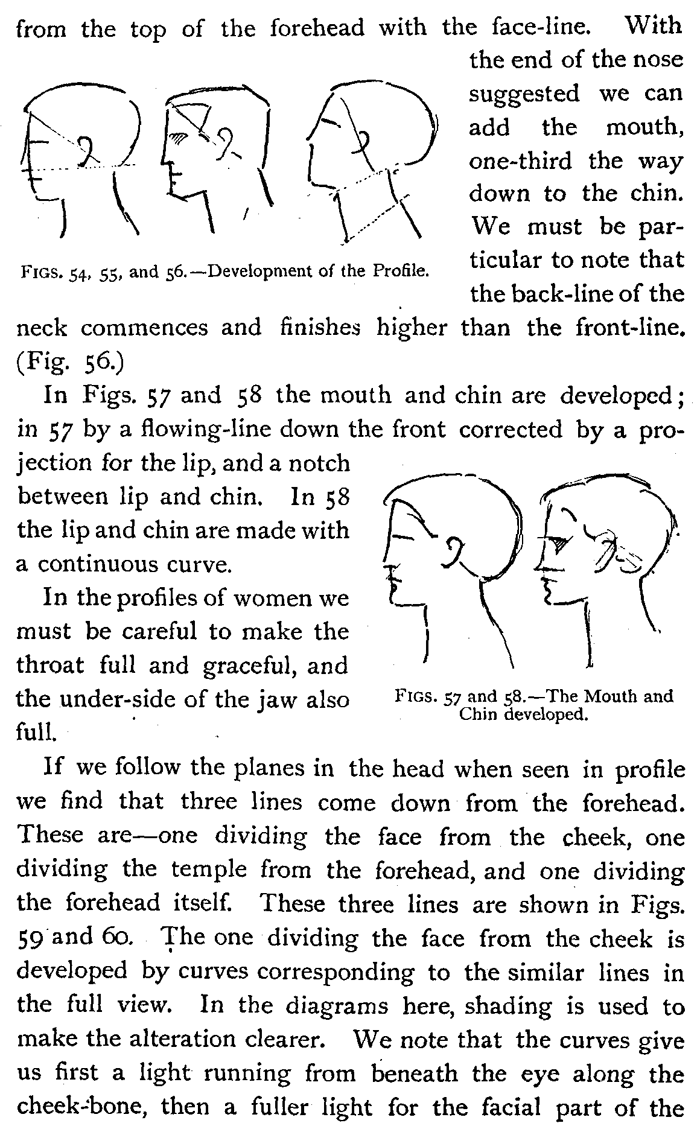

The first lines for a profile are commonly those shown in Figs. 52 and 53, which are respectively of a woman and of a man. We note that the hair-line, from the forehead to the ear, divides the face from the cranium and leaves them about equal in area (the face \ the smaller) ; that the line for FIGS. 52 and 53.—First Lines of the the front of the face can be divided into three equal divisions for the brow and the end of the nose ; that the top of the head rises as it recedes, definitely in woman, less definitely in man ; that the line at the back of both head and neck is, in woman, a beautiful curve, while in man it is more vertical and less continuous. We note also that the hair-line in man must be sharply deflected, and that the same grace or squareness that characterizes the back of the neck in woman or man respectively must also characterize the front of it. But for the front of the face a single line is not of much service. The projection of the nose makes it imperative to separate very soon the upper from the lower part. Hence we have Figs. 54, 55, and 56. The line down the nose may be said to radiate

forehead with the face-line. With the end of the nose suggested we can add the mouth, one-third the way down to the chin. We must be particular to note that the back-line of the neck commences and finishes higher than the front-line. (Fig. 56.)

In Figs. 57 and 58 the mouth and chin are developed ; in 57 by a flowing-line down the front corrected by a projection for the lip, and a notch between lip and chin. In 58 the lip and chin are made with a continuous curve.

In the profiles of women we must be careful to make the throat full and graceful, and the under-side of the jaw also full.

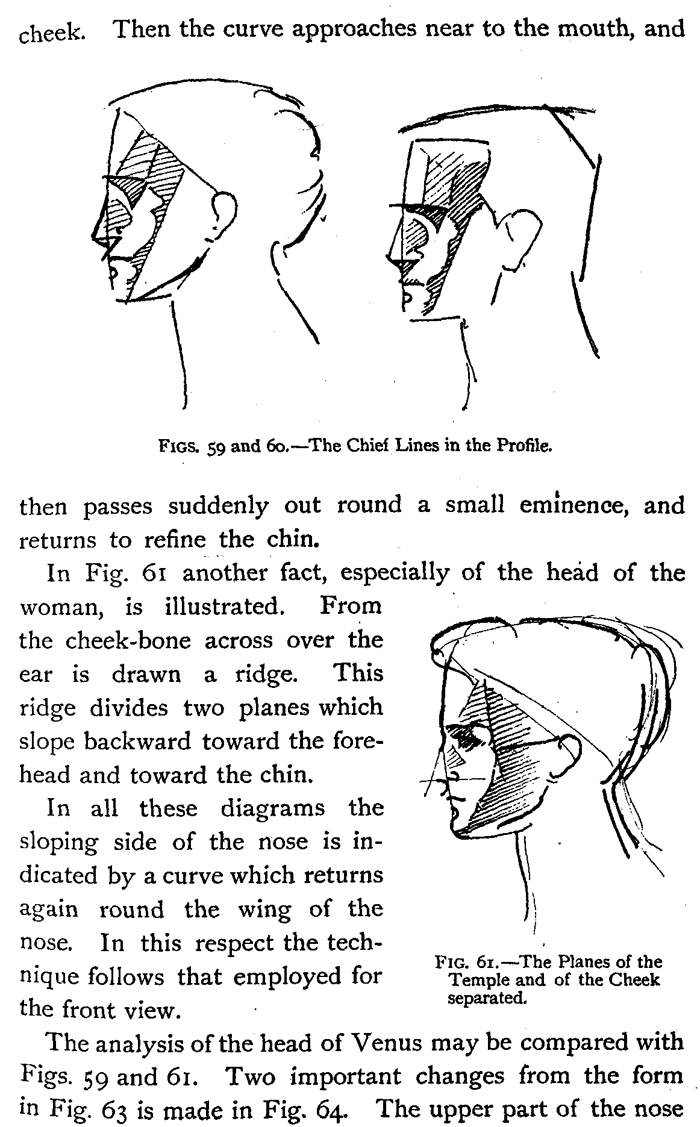

If we follow the planes in the head when seen in profile we find that three lines come down from the forehead. These are—one dividing the face from the cheek, one dividing the temple from the forehead, and one dividing the forehead itself. These three lines are shown in Figs. 59 and 6o. The one dividing the face from the cheek is developed by curves corresponding to the similar lines in the full view. In the diagrams here, shading is used to make the alteration clearer. We note that the curves give us first a light running from beneath the eye along the cheek-bone, then a fuller light for the facial part of the cheek. Then the curve approaches near to the mouth, and then passes suddenly out round a small eminence, and returns to refine the chin.

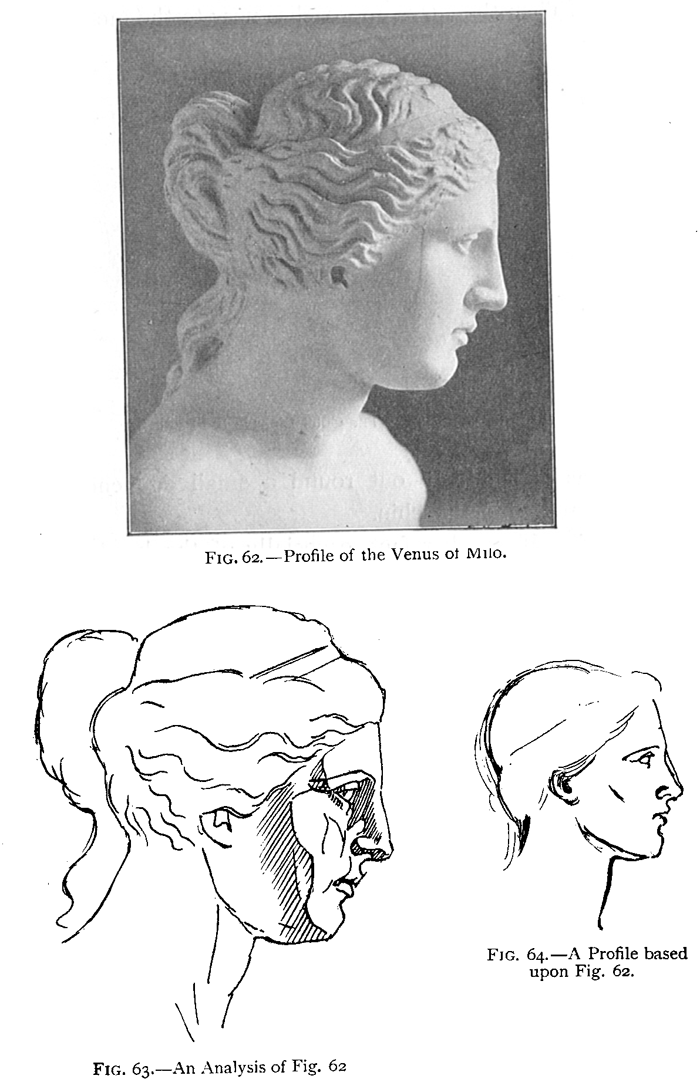

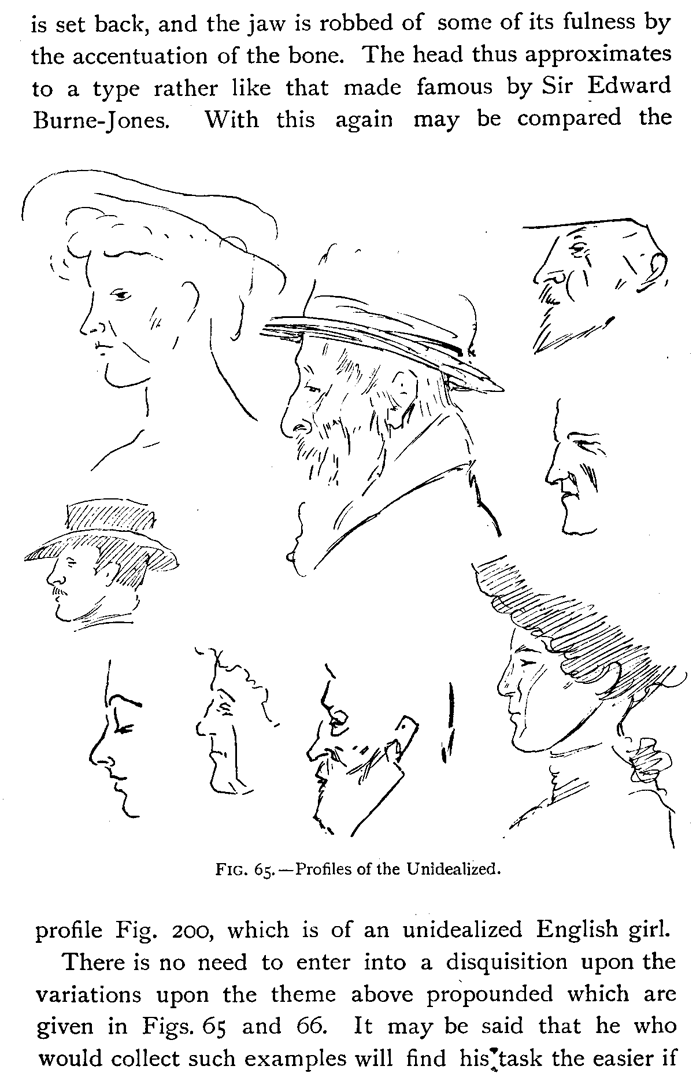

In Fig. 61 another fact, especially of the head of the woman, is illustrated. From the cheek-bone across over the ear is drawn a ridge. This ridge divides two planes which slope backward toward the forehead and toward the chin. In all these diagrams the sloping side of the nose is indicated by a curve which returns again round the wing of the nose. In this respect the technique follows that employed for the front view. The analysis of the head of Venus may be compared with Figs. 59 and 61. Two important changes from the form in Fig. 63 is made in Fig. 64. The upper part of the nose is set back, and the jaw is robbed of some of its fullness by the accentuation of the bone. The head thus approximates to a type rather like that made famous by Sir Edward Burne-Jones. With this again may be compared the profile Fig. 200, which is of an un-idealized English girl.

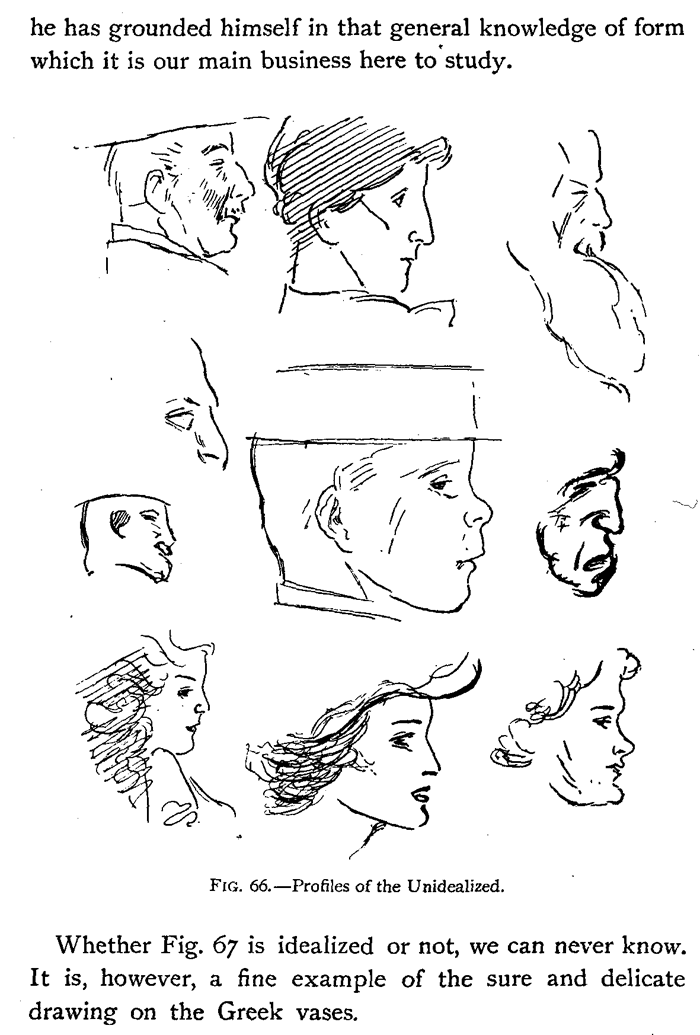

There is no need to enter into a disquisition upon the variations upon the theme above propounded which are given in Figs. 65 and 66. It may be said that he who would collect such examples will find his:task the easier if

he has grounded himself in that general knowledge of form which it is our main business here to study.

Whether Fig. 67 is idealized or not, we can never know. It is, however, a fine example of the sure and delicate drawing on the Greek vases.

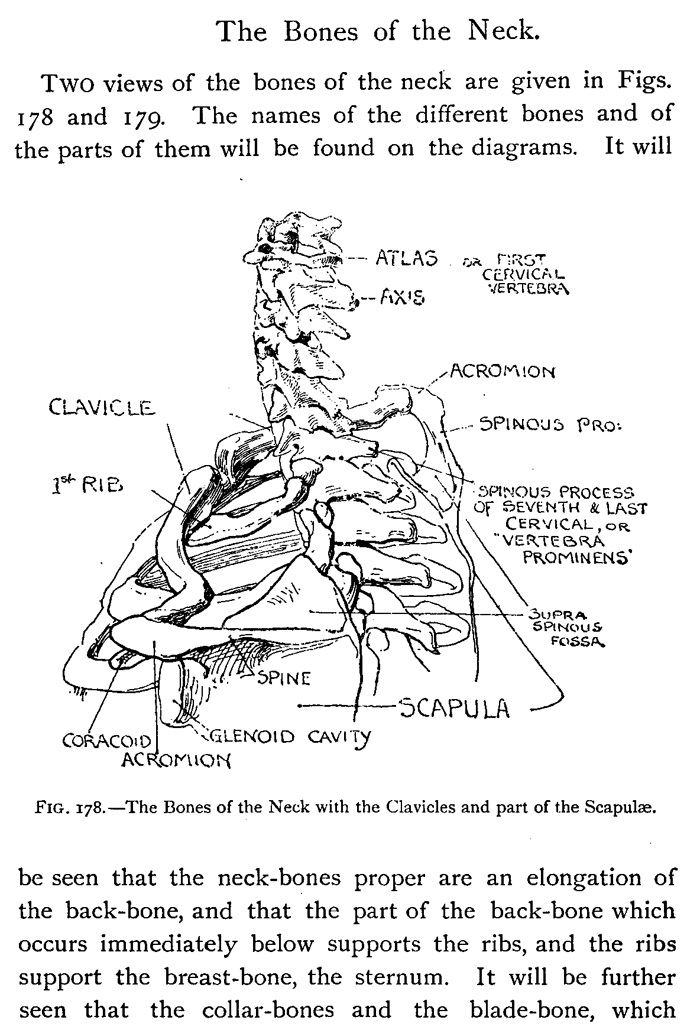

The Bones of the Neck.

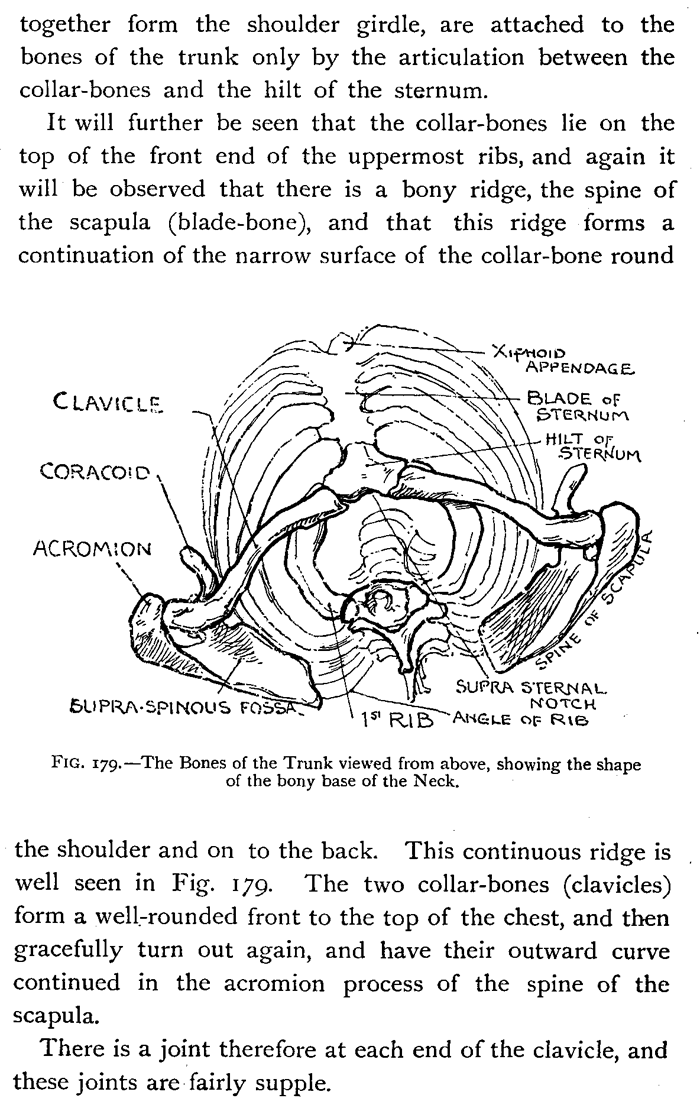

Two views of the bones of the neck are given in Figs. 178 and 179. The names of the different bones and of the parts of them will be found on the diagrams. It will be seen that the neck-bones proper are an elongation of the back-bone, and that the part of the back-bone which occurs immediately below supports the ribs, and the ribs support the breast-bone, the sternum. It will be further seen that the collar-bones and the blade-bone, which together form the shoulder girdle, are attached to the bones of the trunk only by the articulation between the collar-bones and the hilt of the sternum.

It will further be seen that the collar-bones lie on the top of the front end of the uppermost ribs, and again it will be observed that there is a bony ridge, the spine of the scapula (blade-bone), and that this ridge forms a continuation of the narrow surface of the collar-bone round the shoulder and on to the back. This continuous ridge is well seen in Fig. 179. The two collar-bones (clavicles) form a well-rounded front to the top of the chest, and then gracefully turn out again, and have their outward curve continued in the acromion process of the spine of the scapula.

There is a joint therefore at each end of the clavicle, and these joints are fairly supple. At the moment, we are considering the bones in relation to the neck, and notice therefore that this continuous ridge made by the clavicles, the acromion, and the spine of the scapula forms the outer base of the neck, while the uppermost pair of ribs forms the inner base. Both of these are of the very greatest importance.

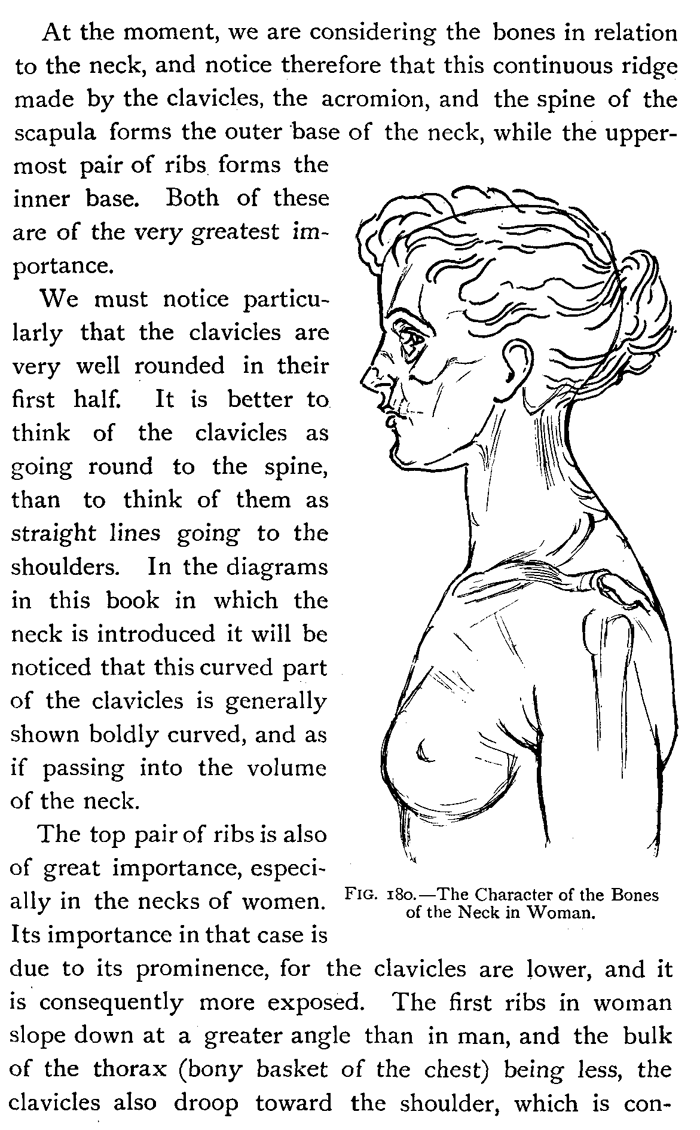

We must notice particularly that the clavicles are very well rounded in their first half. It is better to think of the clavicles as going round to the spine, than to think of them as straight lines going to the shoulders. In the diagrams in this book in which the neck is introduced it will be noticed that this curved part of the clavicles is generally shown boldly curved, and as if passing into the volume of the neck.

The top pair of ribs is also of great importance, especially in the necks of women. Its importance in that case is due to its prominence, for the clavicles are lower, and it is consequently more exposed. The first ribs in woman slope down at a greater angle than in man, and the bulk of the thorax (bony basket of the chest) being less, the clavicles also droop toward the shoulder, which is consequently rather lower. All this gives prominence to the upper part of the top ribs, which therefore gain in importance. Indeed, it is no exaggeration to call the top pair of ribs the inner base in the neck of a woman, for its influence on the form is unmistakable. It is they that help to support the necklaces. Let, us notice that these ribs form with the inner or convex part of the clavicles a fairly continuous surface, as if, indeed, the clavicles did not pass to the shoulders at all.

We must now notice that the inner and outer bases are not in the same plane. The inner (the top ribs) slope downward, the outer (the clavicles and the spines of the scapulae) slope backwards and downwards.

We must notice finally that the obliquity we have observed in the lower part of the neck in woman is extended also to the upper part. The back of a woman's skull slopes up somewhat, whereas that of a man is squarer. The result is that the neck of woman is lengthened both behind and before.

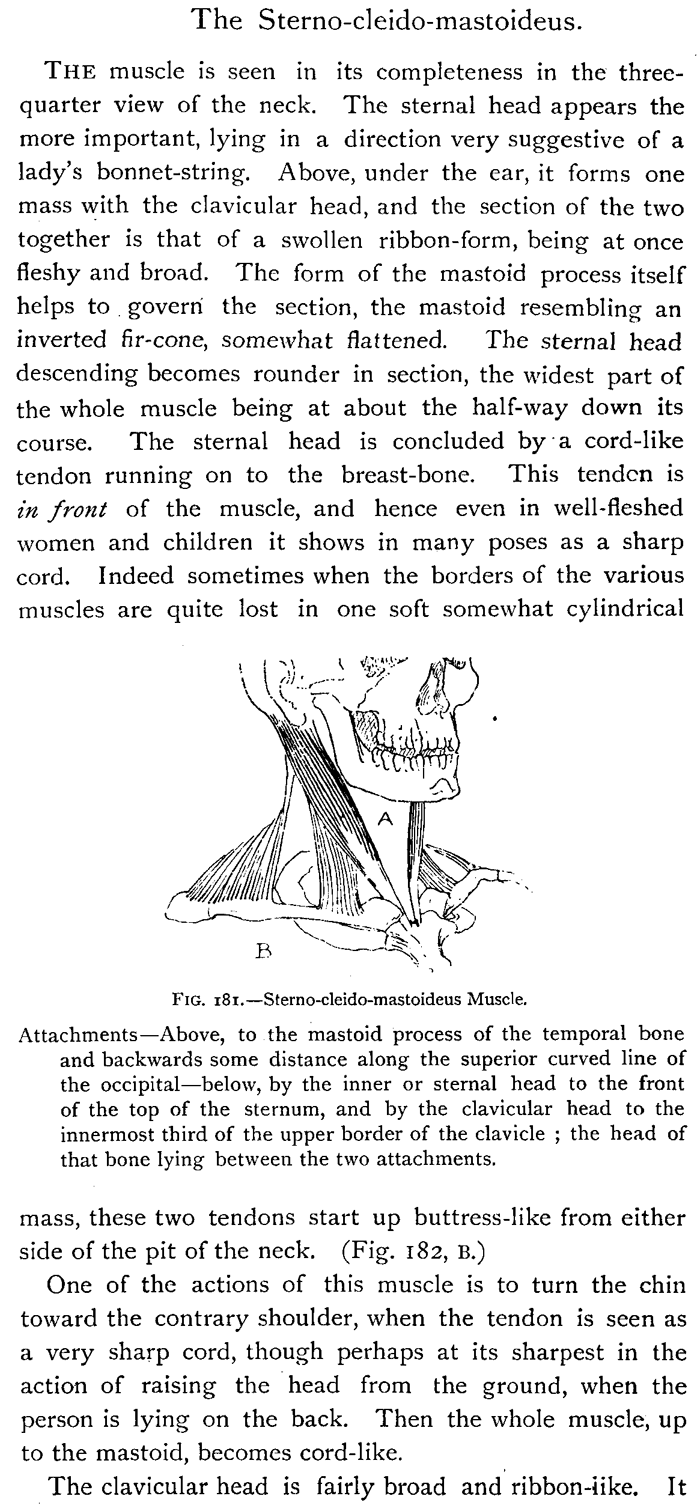

The Sterno-cleido-mastoideus.

The muscle is seen in its completeness in the three-quarter view of the neck. The sternal head appears the more important, lying in a direction very suggestive of a lady's bonnet-string. Above, under the ear, it forms one mass with the clavicular head, and the section of the two together is that of a swollen ribbon-form, being at once fleshy and broad. The form of the mastoid process itself helps to govern the section, the mastoid resembling an inverted fir-cone, somewhat flattened. The sternal head descending becomes rounder in section, the widest part of the whole muscle being at about the half-way down its course. The sternal head is concluded by a cord-like tendon running on to the breast-bone. This tendon is in front of the muscle, and hence even in well-fleshed women and children it shows in many poses as a sharp cord. Indeed sometimes when the borders of the various muscles are quite lost in one soft somewhat cylindrical Attachments—Above, to the mastoid process of the temporal bone and backwards some distance along the superior curved line of the occipital—below, by the inner or sternal head to the front of the top of the sternum, and by the clavicular head to the innermost third of the upper border of the clavicle ; the head of that bone lying between the two attachments.

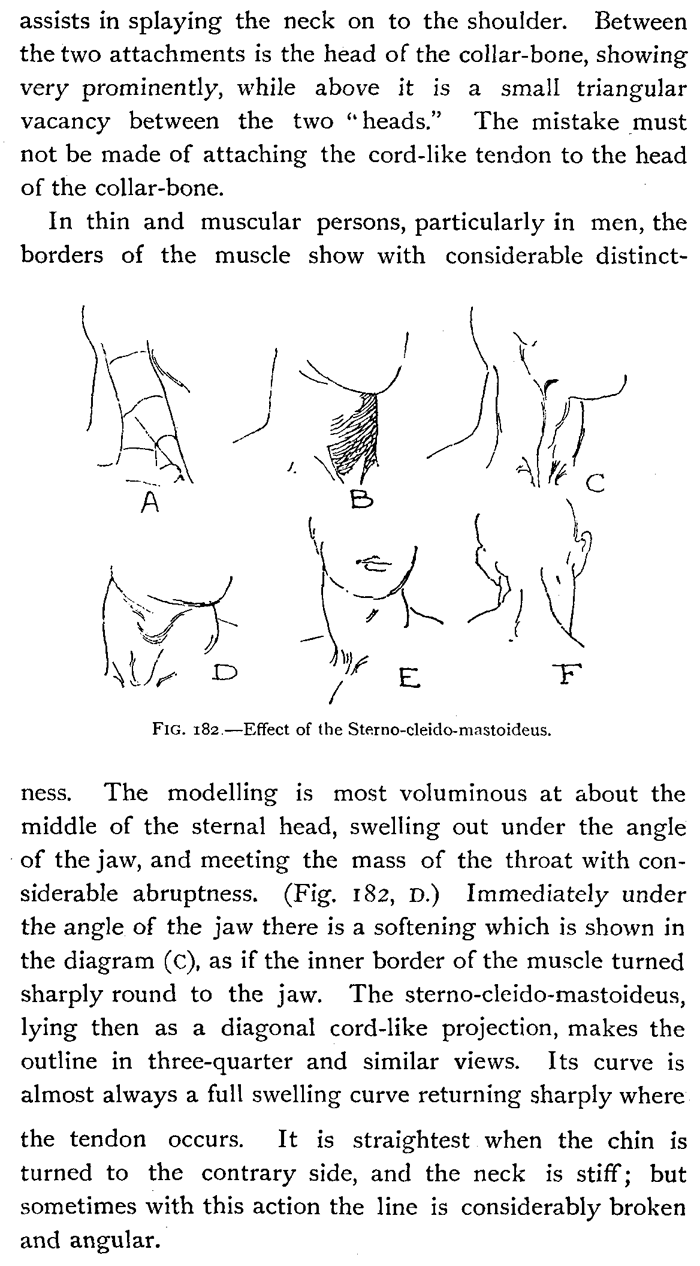

One of the actions of this muscle is to turn the chin toward the contrary shoulder, when the tendon is seen as a very sharp cord, though perhaps at its sharpest in the action of raising the head from the ground, when the person is lying on the back. Then the whole muscle, up to the mastoid, becomes cord-like.

The clavicular head is fairly broad and ribbon-like. It assists in splaying the neck on to the shoulder. Between the two attachments is the head of the collar-bone, showing very prominently, while above it is a small triangular vacancy between the two " heads." The mistake must not be made of attaching the cord-like tendon to the head of the collar-bone.

In thin and muscular persons, particularly in men, the borders of the muscle show with considerable distinctness. The modeling is most voluminous at about the middle of the sternal head, swelling out under the angle of the jaw, and meeting the mass of the throat with considerable abruptness. (Fig. 182, D.) Immediately under the angle of the jaw there is a softening which is shown in the diagram (C), as if the inner border of the muscle turned sharply round to the jaw. The sterno-cleido-mastoideus, lying then as a diagonal cord-like projection, makes the outline in three-quarter and similar views. Its curve is almost always a full swelling curve returning sharply where the tendon occurs. It is straightest when the chin is turned to the contrary side, and the neck is stiff; but sometimes with this action the line is considerably broken and angular.

The Head and Neck of a Child.

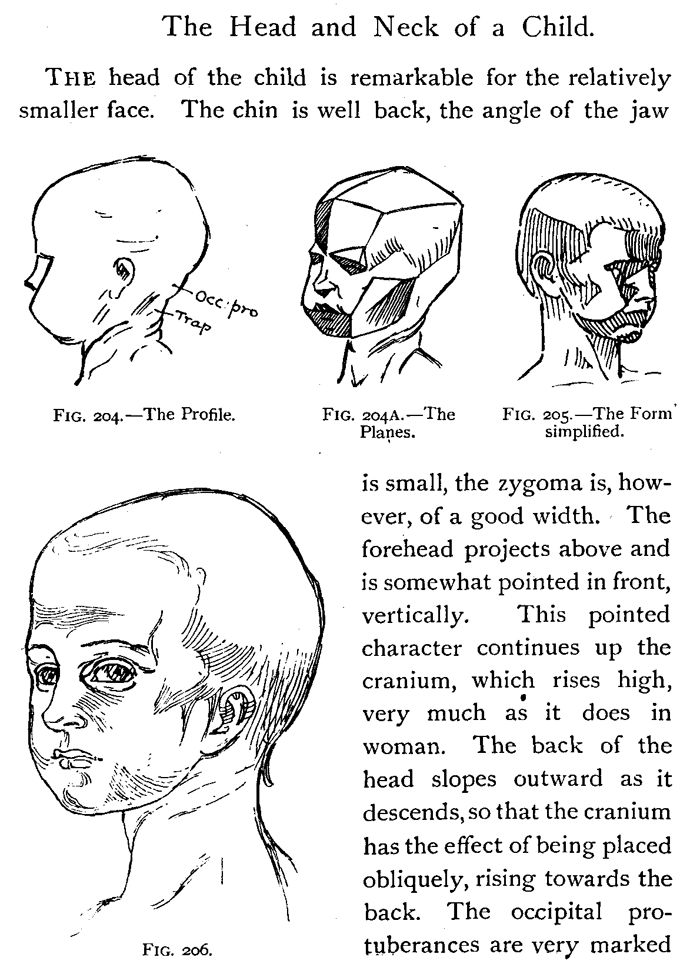

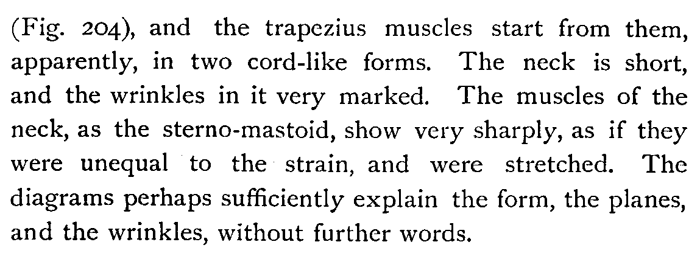

The head of the child is remarkable for the relatively smaller face. The chin is well back, the angle of the jaw is small, the zygoma is, however, of a good width. The forehead projects above and is somewhat pointed in front, vertically. This pointed character continues up the cranium, which rises high, very much as it does in woman. The back of the head slopes outward as it descends, so that the cranium has the effect of being placed obliquely, rising towards the back. The occipital protuberances are very marked (Fig. 204), and the trapezius muscles start from them, apparently, in two cord-like forms. The neck is short, and the wrinkles in it very marked. The muscles of the neck, as the sterno-mastoid, show very sharply, as if they were unequal to the strain, and were stretched. The diagrams perhaps sufficiently explain the form, the planes, and the wrinkles, without further words.