Home > Directory Home > Drawing Lessons > How to Draw Caricatures & Cartoon Faces > Special Pen and Ink Techniques

PEN AND INK DRAWING TECHNIQUES FOR ARTISTS WHO DRAW CARTOONS, CARICATURES, AND COMICS

|

GO BACK TO THE HOME PAGE FOR CARICATURE DRAWING TUTORIALS

[The above words are pictures of text, below is the actual text if you need to copy a paragraph or two]

PEN AND INK TECHNIQUES

WHILE beginners attach an undue importance to technique, it is probably true that the average art school devotes too little attention to this vital subject.

It would seem to admit of no argument that a workman should become acquainted with his tools. A carpenter must know how to hold a nail in one hand and a hammer in the other before he attempts to use nails to join separate pieces of wood. Arguing thus, why should an artist fail to learn, first of all, how to hold the tools he works with in relation to the surface on which he works, and how to propel these tools in order to achieve any desired result?

Broadly speaking, technique may be divided into two classes : painting (or working in solid tones) and drawing with the point (or working in line).

As a rule it is customary for the beginner to work in tones, or masses, because they are approximately nearer to what he sees than a line effect would be.

The mediums generally used for working in solid tones are oil color, water color, pastel, and charcoal. The mediums best adopted for line drawing are pen. and-ink, pencil, crayon, and charcoal.

While the caricaturist usually works with the point. (thus producing line effects) it is wise to have a preparatory technical training in the use of masses of solid grays, blacks, and whites.

It should be remembered that sets of lines are used merely as arbitrary representations of tones, and that each line, thus used, is but a unit of a tone.

The direction in which lines (as units of tone) should be drawn is often a very puzzling problem to the tyro. A little thought will soon prove that to let the lines run in the longest possible direction is the quickest and most practical way to attain a desired effect. For instance, in attempting to represent a telegraph pole in one flat tone of gray, it would require a great number of strokes and much effort to represent this gray by horizontal lines; perpendicular lines, however, would enable the draughtsman to command this subject with a few long strokes. A trained workman always gets results with the fewest motions; this applies to art as well as to any other craft. Unnecessary work is particularly objection.

able in a cartoon, because a joke should never be told in a labored way.To gain a practical knowledge of the possibilities of line, it is perhaps wiser to practice, at first, with an ordinary writing pen. A stub pen, of course, should not be used.

It is not a bad idea to use black draughtsman's ink at the outset, because it works so differently from writing ink. Many beginners complain that the average drawing ink is too thick—that it does not flow with enough readiness. This is a mistaken notion; the drawing ink should always be used as it comes from the bottle, and never diluted with water. Thorough acquaintance with this medium will prove the necessity of having it rather denser in volume than is customary with writing fluids. Many black drawing inks are pure carbon, held in suspension, and the last quarter of the bottle often carries considerable sediment. This fault may be readily overcome by adding a few drops of liquid ammonia.

Higgins' American drawing inks (waterproof and non-waterproof) are universally used and liked by pen draughtsmen. The black inks manufactured for artists' use by the Carter Ink Co., F. Weber & Co., Bourgeoise Freres, and Winsor & Newton are also in favor. Each of these makes has its individual peculiarities; some flow rather freely and lie very flat, while others flow slowly and pile up somewhat in the heavy masses.

Which brand shall be used exclusively depends entirely upon the personal taste of the artist, and an intelligent choice can only be made after repeated experiment. After reasonable acquaintance with the properties of drawing ink, used on a writing pen, practice on a draughting may be undertaken.

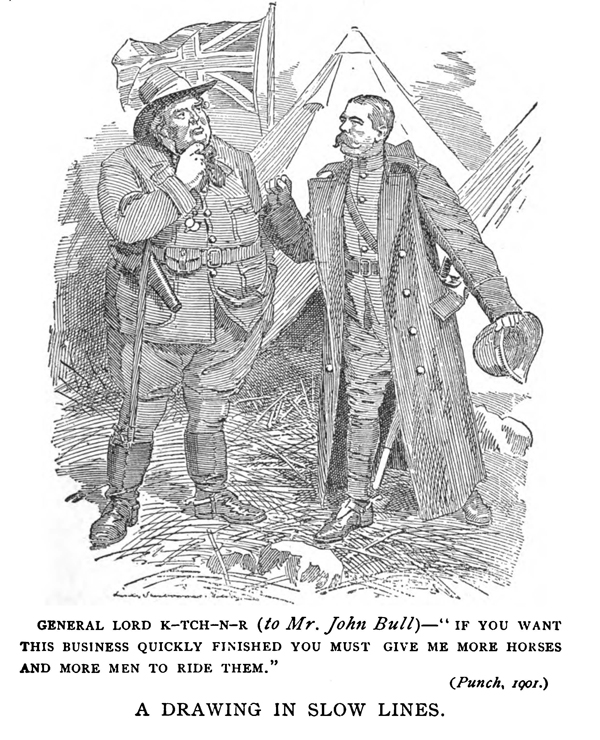

A DRAWING IN SLOW LINES.

Draughting pens vary even more than draughting inks, and here, again, individual taste must play a large part in the final selection of a permanent tool. A Gillott's 290 pen makes a very fine hair stroke, and by sufficient pressure on a properly loaded point can also be made to yield a fat, rich black line. For this reason, this tool has a great vogue with all classes of pen- draughtsmen. Its elasticity is probably as great as that of any drawing pen in common use. Gillott's Nos. 303 and 170 are less elastic and better adapted to the hand of an artist whose inclination is to bear heavily on the surface upon which he is working. Perry's 6or pens are made in England. They are rather difficult to obtain in this country, but are worth searching for; artists who have become acquainted with their merits usually accord them an honored place among their working utensils. Blanzy-Poure crowquills are very finely wrought pens, mounted on a cylindrical base of like material, and attached to thin wooden handles. They find high favor with those who prefer to work on a minute scale. Many newspaper artists, cartoonists particularly, like Ester-brook's 048 Lady Falcon Pens. These (being made to write with) are quite stiff and unyielding in comparison with draughting pens, but, when properly handled, give a coarse, clear line particularly adapted for reproduction by the photo-engraving process and for clear printing on coarse newspaper stock.

Next in importance to correct drawing, and proper rendition of tone, is the quality of line in a pen-drawing. A drawing may be produced by a series of long or short lines, slowly drawn; or by a series of long lines, rapidly drawn; or by combining slow and rapid lines.

Lines drawn slowly may be made to conform to any given contour without lifting the point which produces them from the paper. Outlines drawn with a rapid stroke, however, necessitate lifting the point from the paper at every sharp angle. The different quality of these two sorts of lines should be carefully studied in the reproduced (or, if possible, original) work of good pen artists.

DRAWING SHOWING HOOKED AND ZIGZAG LINES.

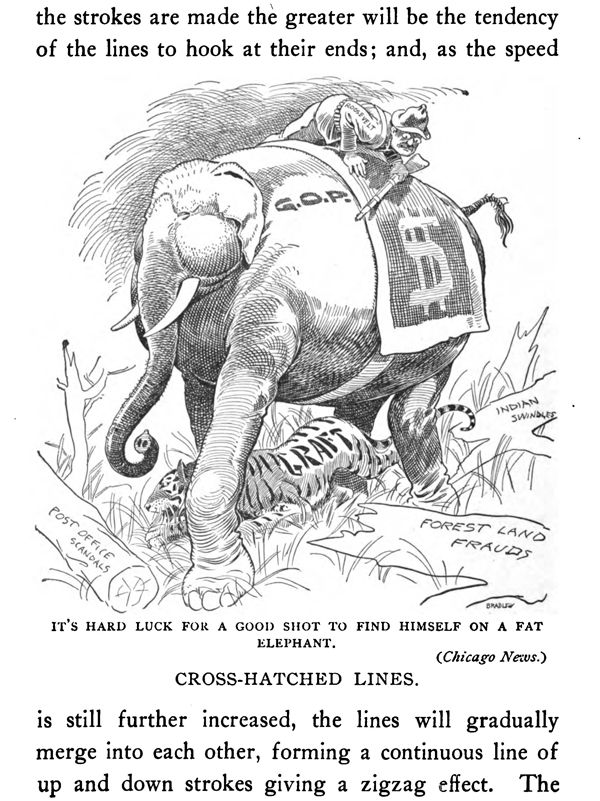

In laying a tone of gray, composed of rapidly drawn lines, it will be found that the more quickly the strokes are made the greater will be the tendency of the lines to hook at their ends; and, as the speed is still further increased, the lines will gradually merge into each other, forming a continuous line of up and down strokes giving a zigzag effect.

The diagram herewith shows rapid lines merging into hooked lines, and thence into a zigzag effect.

Of course, slow lines never have hooked ends, neither do they run into a zigzag effect.

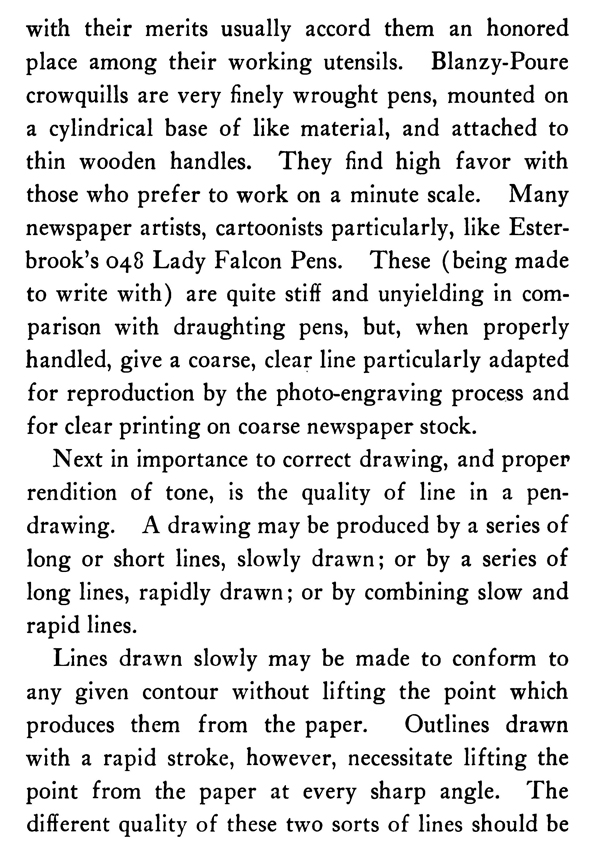

CROSS-HATCHED LINES.

Cross-hatched lines are sets of lines running at right angles over other sets of the same width and at the same distance apart. Cross-hatched effects have, in the past, been used to excess by many well-known cartoonists; but the modern tendency is in the direction of simpler treatment, cross-hatching being relegated as it should be to backgrounds or such parts of the picture as must be disentangled from their surrounding parts by a different technical treatment. Three objects, side by side, of three vivid, distinct colors might—when reduced to grays—appear of the same color. In such a case cross-hatching would be of obvious value, for, by its means, two grays of exactly similar tone might be made to show different color quality.

Cross-hatched lines are also useful to represent differences in texture. Iron, wood, cloth, and various other textures would have a tendency to look entirely alike, when reduced to lines, if the draughtsman had at his command but one set of strokes. Double or twin strokes are often used in masses, to gain variety of color or texture; in fact, a special pen has been invented for this purpose, although its use cannot be strongly advised, because lines drawn with it have a rather mechanical effect. Pen-draughtsmen often use stippling, or pen dots, to give variety of technical effect, or to finish an entire picture in detail. Cartoonists, as a rule, merely use stippling as an occasional effect in some special case.

STIPLLING TECHNIQUE

Somewhat the same effect as stippling can be obtained by the use of lithographic or grease crayon on a grained surface, if the crayon strokes are not put on in lines but as a mass.

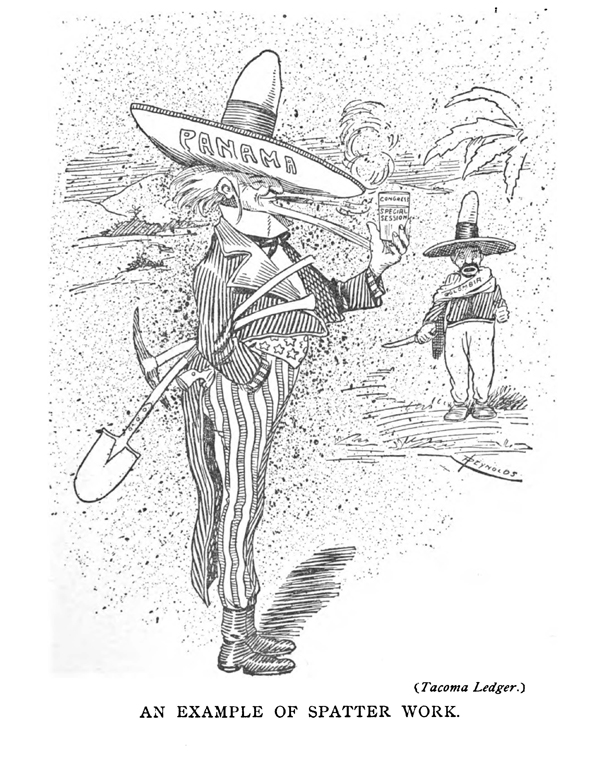

SPATTERING TECHNIQUE

Somewhat allied to the stipple effects is spatter-work. A spatter tone may be applied to any part of a picture by cutting a stencil of the desired shape of the tone; preferably from rather stiff cardboard. This cardboard stencil may be pinned, or held by weights, in its proper place on the drawing, and the spatter applied by a tooth-brush dipped in ink, which can be spattered on the drawing by dragging a penknife blade sharply over the hairs of the brush.

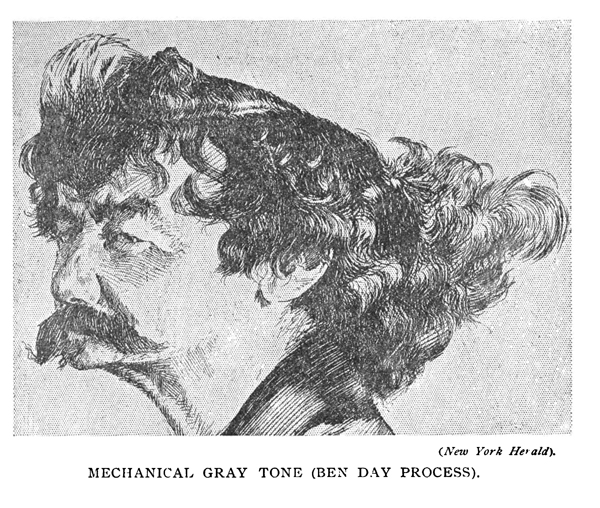

Stipple, spatter, and various other gray effects, including ruled-line grays, may be introduced in a drawing by means of a mechanical device invented by Mr. Benjamin Day. This is commonly called the Ben Day Machine, and most large newspapers and engraving plants have at least one of them for the use of their artists. These machines are leased, not sold, and are quite expensive.

Ross's stipple papers (or scratch boards) will yield effects very similar to the Ben Day machine and cost comparatively little. These surfaces all have a base of cardboard heavily coated with chalk and are ,of three sorts : embossed, printed, and embossed and printed. The embossed sorts are made in stippled or grained patterns and when drawn on with grease crayon give beautiful effects. Owing to the heavy coating of chalk, high lights can be readily scraped into the grays with a sharp penknife. The printed Ross papers come in tones of gray, composed of lines, crossed lines, etc. On the plain printed surfaces penand-ink, br'ush blacks, and scraped-away white effects are possible, but grease crayon cannot be used, as this surface has no tooth, or grain, for the crayon to catch. The embossed printed Ross papers will give all the effects of the plain printed papers and in addition may be used as a surface fcr grease crayon. Scratch effects have not, thus far, been very extensively used by American comic artists, but in Europe they are held in high favor.

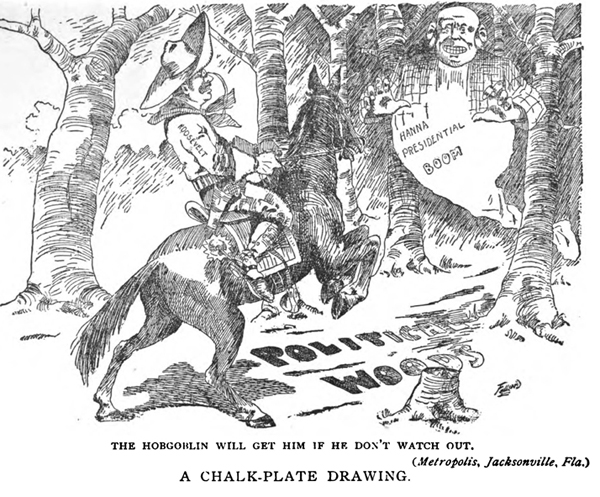

It should be explained that grease crayon comes in three qualities: hard, medium, and soft. For caricaturists' use it is preferable to black chalk (conte crayon) because it will not rub from any surface to which it is attached. After leaving an artist's hands, drawings are often subject to rough handling, and fugitive mediums like chalk are therefore undesirable. In some of the smaller cities daily papers find it impracticable, or too expensive, to use the photoengraving process for reproducing cartoons or other drawings made with the pen. What are called chalk plates are, therefore, resorted to, and while this process does not yield the brilliant clear results of a zinc etching (or line engraving, as it is usually called), it produces sufficiently good work to satisfy the demands of the less important daily papers.

MECHANICAL GRAY TONE (BEN DAY PROCESS)

A chalk plate is a thin piece of sheet steel, with a blackened surface, on which has been deposited a coating of chalk about one -thirty-second of an inch thick. The picture is first lightly indicated upon the surface of this chalk by a tool, with a hooked point made especially for chalk-plate work. The finished drawing is made by using precisely the same technique as for a pen-drawing, and by scraping the lines through the chalk to the black surface of the steel plate. In order to see the design the artist must, as he proceeds, continually blow away the chalk dust caused by cutting through the coating. Flat tones of black may be obtained by the use of a penknife. After a drawing has been carried out in this manner, a printing plate can be made from it by pouring type metal into the die composed of the chalk and steel. The resulting plate must then be mounted on a piece of wood to make it type-high; it is then ready for the printer. The artist seldom carries the process beyond scraping the design on the chalk plate, the stereotyping is therefore not a necessary thing for him to learn. Chalk plates, and tools for working on them, may be obtained from Carl Schraubstadter, St. Louis, Mo. They are quite inexpensive, and if it is the intention of the student to work on a newspaper outside of the large cities, he should familiarize himself with them.

Many surfaces are used by cartoonists to draw upon, Bristol-board probably being the most in favor. In buying Bristol-board, care should be taken to select a board composed entirely of paper stock. Bristol-boards are on the market which are heavily coated with chalk. With the exception or the Ross papers, these chalk-coated surfaces are not desirable to draw on with the pen, as the pen point digs up the surface and the ink flows in an irregular manner, entirely refusing to obey the draughtsman.

Steinbach and smooth Strathmore papers are excellent surfaces for pen-drawings, having rather more tooth, or grain, than Bristol-board. These two kinds of paper are particularly useful when the introduction of grease effects is desired, Bristol.board being so slippery that it is impossible to work on it with crayon of any sort.

Though cartoons are seldom made in water or oil color, a knowledge of how to handle the brush is desirable to the aspiring cartoonist, because, in these days of color printing, pen-drawing proofs must frequently be finished in water colors as guides for the engraver of the color plates.

In order to lay a perfectly even tone of water color, the drawing to be colored should be attached to a drawing board, and tipped at a rather decided angle. The brush should be loaded as heavily as possible with color, in which there is plenty of water. The spaces to be colored should be covered from the top downward, allowing gravity to pull the color toward the worker and to smooth out irregularities automatically. The painted surface should not be touched while wet. A water-color tablet is a practical utensil on which to mix color. At its side should be placed a good-sized bowl filled with clear water, and an absorbent rag upon which to dry the brush.

Red or black sable brushes, round or flat, are usually considered the best for water color. A medium-sized brush is the best for general work, and is usually all that will be found necessary to color cartoons or comic pictures.

Privacy Policy .... Contact Us