Home > Directory Home > Drawing Lessons > How to Draw Caricatures & Cartoon Faces > Learn How to Draw Cartoons, Caricatures, Comics and Other Artwork by Observing Nature

LEARN HOW TO DRAW CARTOONS, COMICS, AND CARICATURES BY OBSERVING YOUR SURROUNDINGS AND SKETCHING IN A SKETCHBOOK

|

GO BACK TO THE HOME PAGE FOR CARICATURE DRAWING TUTORIALS

[The above words are pictures of text, below is the actual text if you need to copy a paragraph or two]

NATURE DRAWING

ALL real knowledge of drawing the human figure must be based on preliminary study done directly from the living model. No amount of copying anatomical plates, or even the work of masters, can ever take the place of working face to face with nature. When one looks at a drawing on a flat surface he merely sees one side of an object and the stereoscopic effect is entirely lost. To really know an object and to make it convincing to others an artist must have a thorough realization of its roundness; he must know what is on the side that is turned away from the eyes, even though it does not appear in his picture.

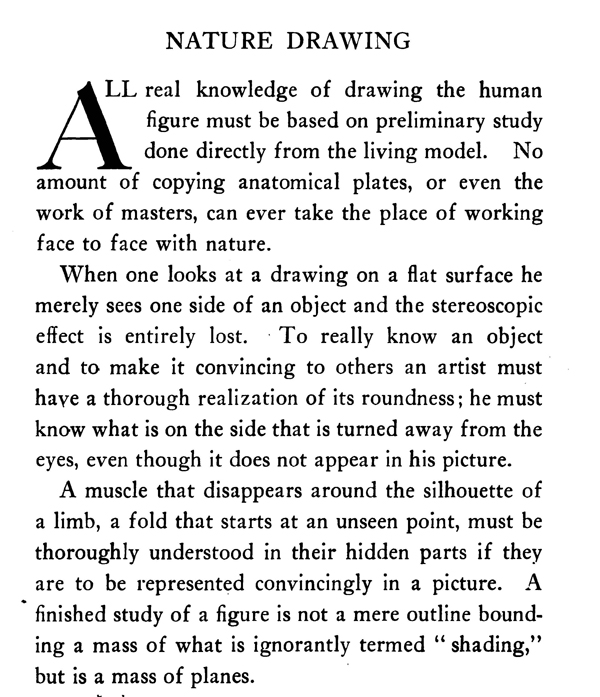

A muscle that disappears around the silhouette of a limb, a fold that starts at an unseen point, must be thoroughly understood in their hidden parts if they are to be represented convincingly in a picture. A finished study of a figure is not a mere outline bounding a mass of what is ignorantly termed " shading," but is a mass of planes.

Planes are the surfaces of different shapes and dimensions which form the contour of any given object.

A DRAWING SHOWING PLANES WITH UNUSUAL CLEARNESS.

A cut diamond, for instance, is a mass of triangular planes, while a packing case presents square or rectangular planes. Probably the most effective way to realize the planes of which any object is composed is to model that object in clay or modeling wax. A student whose knowledge of form has been gained by modeling will never make the mistake of thinking of planes as " shading " when he works on a flat surface. He will strive for planes in his draughtsmanship quite as much as he does with his clay or wax. He will realize that the silhouette a figure presents to the eye is not its only boundary; that the figure shows an infinite number of silhouettes according to the point of view from which it is observed. He will also realize that the shape and size of many of the planes inside the silhouette are quite as important as the silhouette itself. Drawing upon a flat surface presents an important problem with which the modeler need not concern himself. The draughtsman must reckon with color; for, even though an object is reduced to black and white, the differences of color must be taken into account. A man in a black suit, with white linen, brown hair, and the usual wonderful variety of flesh tones, would show no differences of color if reproduced in a clay or wax statue.

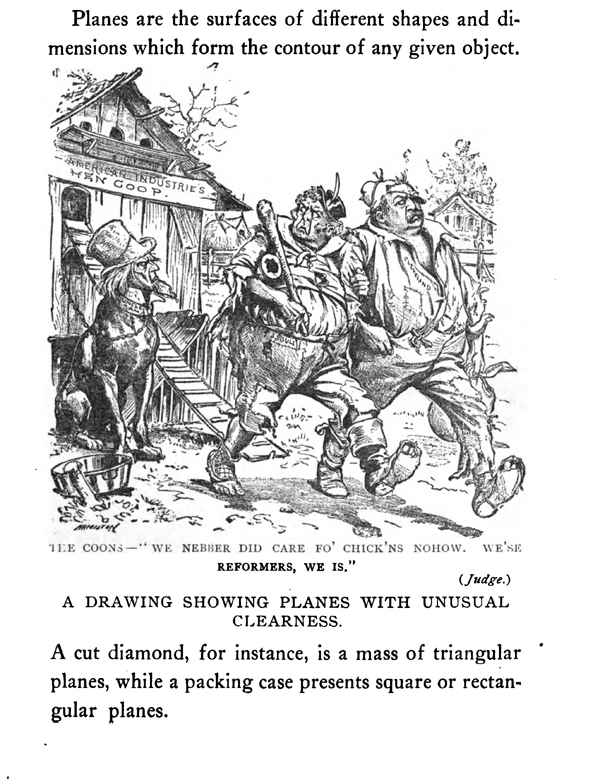

These differences are termed color values, and must always be considered in a drawing showing light and

COLOR VALUES ARE SHOWN IN THE VARIOUS GARMENTS, ETC.

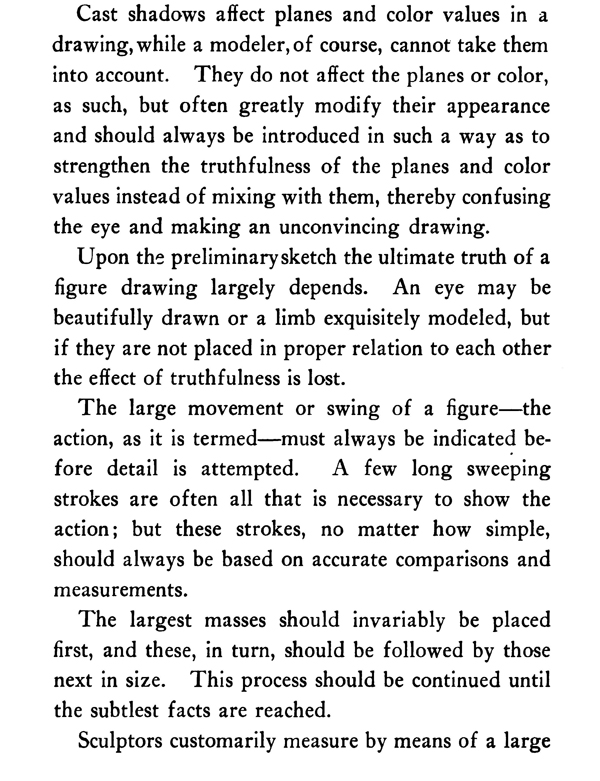

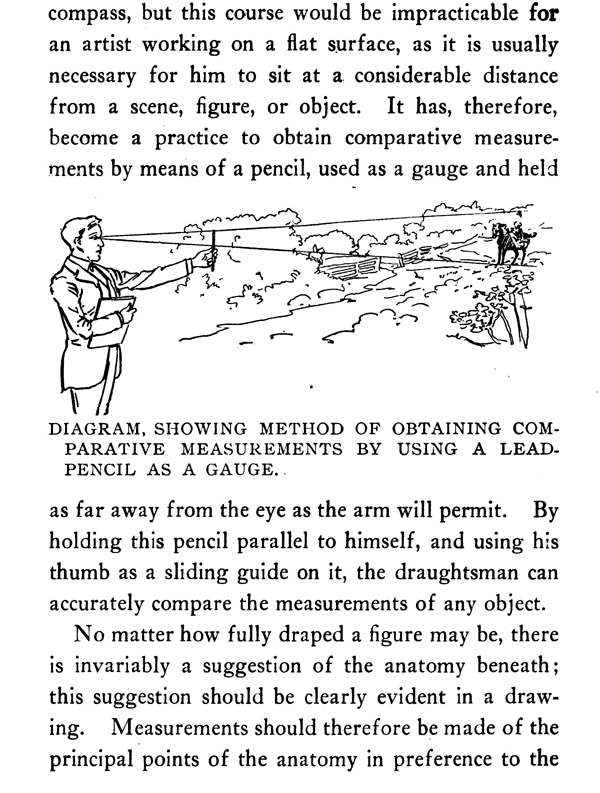

shade. A black coat, for example, must not only be treated in such a way as to clearly bring out its planes, but must show distinctly that it is black.Cast shadows affect planes and color values in a drawing, while a modeler, of course, cannot take them into account. They do not affect the planes or color, as such, but often greatly modify their appearance and should always be introduced in such a way as to strengthen the truthfulness of the planes and color values instead of mixing with them, thereby confusing the eye and making an unconvincing drawing.

Upon the preliminary sketch the ultimate truth of a figure drawing largely depends. An eye may be beautifully drawn or a limb exquisitely modeled, but if they are not placed in proper relation to each other the effect of truthfulness is lost. The large movement or swing of a figure—the action, as it is termed—must always be indicated before detail is attempted. A few long sweeping strokes are often all that is necessary to show the action; but these strokes, no matter how simple, should always be based on accurate comparisons and measurements.

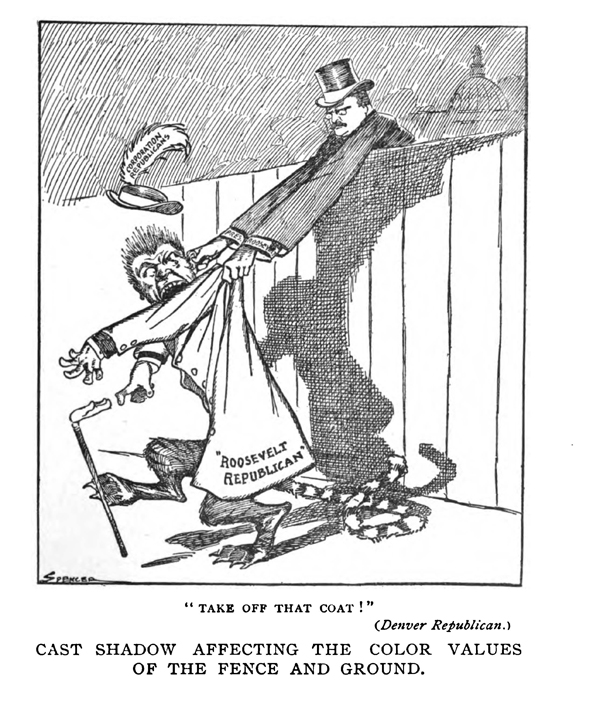

DIAGRAM, SHOWING METHOD OF OBTAINING COMPARATIVE MEASUREMENTS BY USING A LEAD-PENCIL AS A GAUGE.

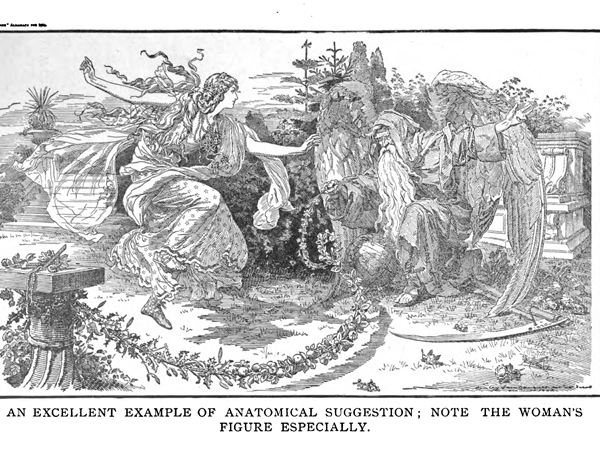

The largest masses should invariably be placed first, and these, in turn, should be followed by those next in size. This process should be continued until the subtlest facts are reached. Sculptors customarily measure by means of a large compass, but this course would be impracticable for an artist working on a flat surface, as it is usually necessary for him to sit at a considerable distance from a scene, figure, or object. It has, therefore, become a practice to obtain comparative measurements by means of a pencil, used as a gauge and held as far away from the eye as the arm will permit. By holding this pencil parallel to himself, and using his thumb as a sliding guide on it, the draughtsman can accurately compare the measurements of any object. No matter how fully draped a figure may be, there is invariably a suggestion of the anatomy beneath; this suggestion should be clearly evident in a drawing. Measurements should therefore be made of the principal points of the anatomy in preference to the principal points of the drapery; for, while the drapery continuously changes as the model rests, or breathes even, the anatomical measurements are always the same.

CAST SHADOW AFFECTING THE COLOR VALUES OF THE FENCE AND GROUND.

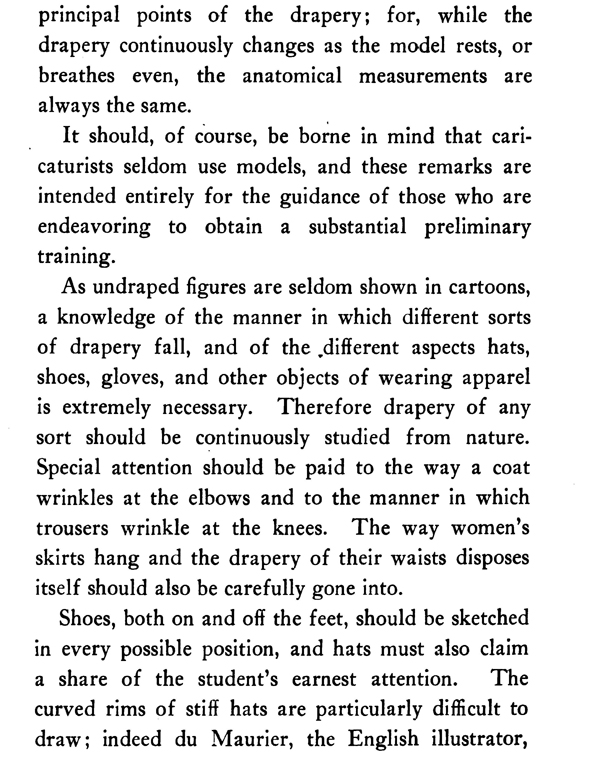

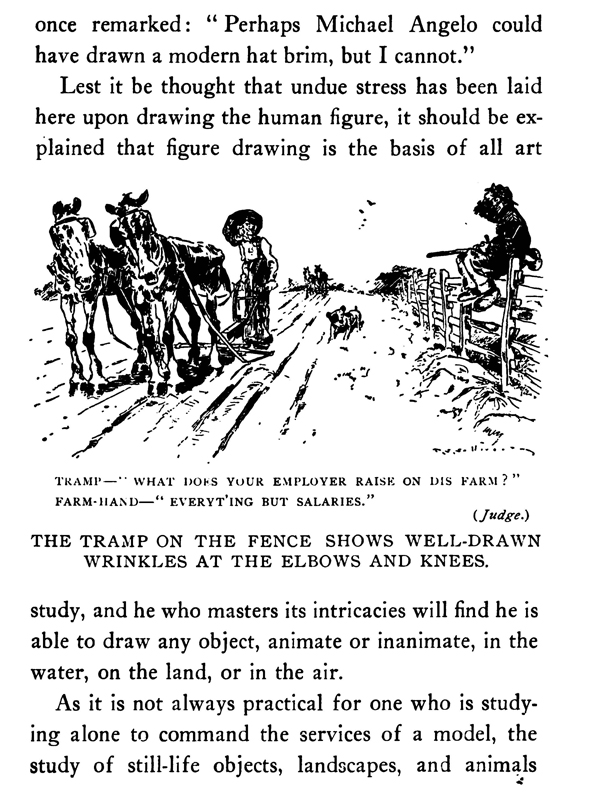

It should, of course, be borne in mind that caricaturists seldom use models, and these remarks are intended entirely for the guidance of those who are endeavoring to obtain a substantial preliminary training. As undraped figures are seldom shown in cartoons, a knowledge of the manner in which different sorts of drapery fall, and of the different aspects hats, shoes, gloves, and other objects of wearing apparel is extremely necessary. Therefore drapery of any sort should be continuously studied from nature. Special attention should be paid to the way a coat wrinkles at the elbows and to the manner in which trousers wrinkle at the knees. The way women's skirts hang and the drapery of their waists disposes itself should also be carefully gone into.

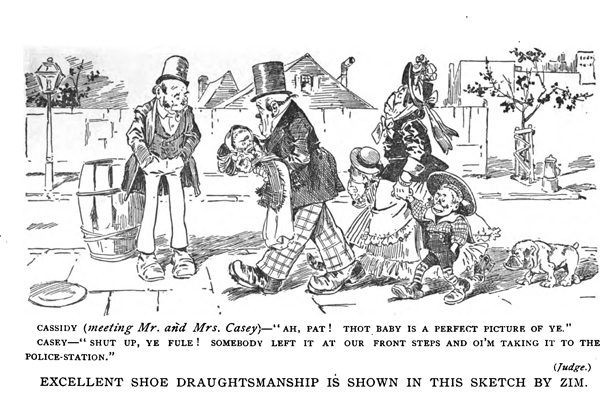

Shoes, both on and off the feet, should be sketched in every possible position, and hats must also claim a share of the student's earnest attention. The curved rims of stiff hats are particularly difficult to draw; indeed du Maurier, the English illustrator, once remarked: " Perhaps Michael Angelo could have drawn a modern hat brim, but I cannot." Lest it be thought that undue stress has been laid here upon drawing the human figure, it should be explained that figure drawing is the basis of all art study, and he who masters its intricacies will find he is able to draw any object, animate or inanimate, in the water, on the land, or in the air.

As it is not always practical for one who is studying alone to command the services of a model, the study of still-life objects, landscapes, and animals can be recommended, not only as a pleasing variation, but as a necessary part of a cartoonist's equipment.

Familiarity with the native shrubs, trees and plants, with many kinds of animals (both wild and domestic), with architecture, and with thousands of objects of everyday use, is essential. All of these things should therefore be drawn from nature repeatedly, and in as many different aspects as possible.

Those who live in the vicinity of large parks, in which there is a zoological collection, have at hand a mine of invaluable information which should be worked to the full limit.

To study .and retain in the memory the shapes of all the objects in use in an ordinary household is in itself a tremendous task and one which should be undertaken with a full appreciation of its difficulty and necessity. Flowers are not -often used by cartoonists, but a knowledge of the principal ones will not be found amiss at times. Even with all that is suggested above carefully memorized and at his fingers' ends, the cartoonist will find himself continually confronted with new problems—new objects to draw.

It is customary with workers in black and white to have a complete, alphabetically arranged file at hand containing photographs and clippings of everything they will probably be called upon to draw. Not the least important parts of these files are those devoted to the portraits of well-known personages who are to take' their parts in the pictorial comedies the artist is continually devising.

It will be found that, as any face is constantly drawn from various points of view, the features impress themselves so indelibly upon the artist's memory that further reference to pictures of that particular personage is no longer necessary; it will even be discovered that the face can be drawn in positions in which the artist has never seen it, and it is here that his previously gained knowledge of modeling and his feeling for planes will make themselves strongly felt. As a sort of library of suggestions of facial characteristics, the cartoonist should keep a notebook in his pocket and should jot down in it accurate outline memorandums of foreheads, noses, mouths, beards, and other parts of the heads he meets in his daily travel.

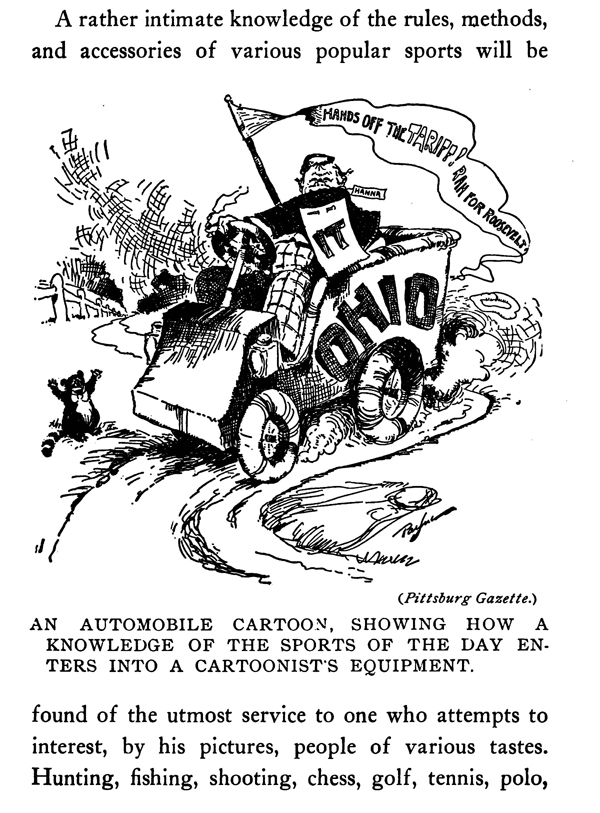

After a few months of such work he will find himself in possession of an immense amount of useful raw material. A rather intimate knowledge of the rules, methods, and accessories of various popular sports will be found of the utmost service to one who attempts to interest, by his pictures, people of various tastes. Hunting, fishing, shooting, chess, golf, tennis, polo, —all the pastimes of the public, rich or poor,—play at some time a part in the cartoonist's work. Of course the sport of the hour is the one which is most frequently called into play by the picture-makers, and as automobiling occupies the principal position among the sports of to-day, a thorough knowledge of the shapes and action of the most common types of automobiles should be obtained. A recent magazine writer has truly said that " the joke-maker and comic draughtsman have discovered in automobilism a veritable Eldorado." Having now indicated, as briefly and clearly as possible in the space at command, the elements of drawing from nature, a subject of the utmost importance to caricaturists will be considered—drawing from memory.

Privacy Policy .... Contact Us