Home > Drawing Directory Home> Drawing in Charcoal > Sketching in Black and White with Pencils & Charcoal

DRAWING AND SKETCHING in Black and White : How to Draw with Charcoal or Graphite Pencils

|

GO BACK TO THE HOME PAGE FOR TUTORIALS FOR BEGINNING ARTISTS

[The above words are pictures of text, below is the actual text if you need to copy a paragraph or two]

ON SKETCHING IN BLACK AND WHITE.

Working in Pencil is far the easiest, and at the same time the most inadequate way of representing nature. It can only be used well for the merest notes. Directly anything finished is attempted where sky is introduced, the effect is poor compared with any other material for producing monochrome drawings. Some years ago J. D. Harding brought pencil work to as great a perfection as possible. It became a fashion, and like a fashion it has gone by. He made full use of all the different qualities of hardness in plumbago, and even invented different forms of lead in the pencil to produce thick or thin or medium lines at pleasure.

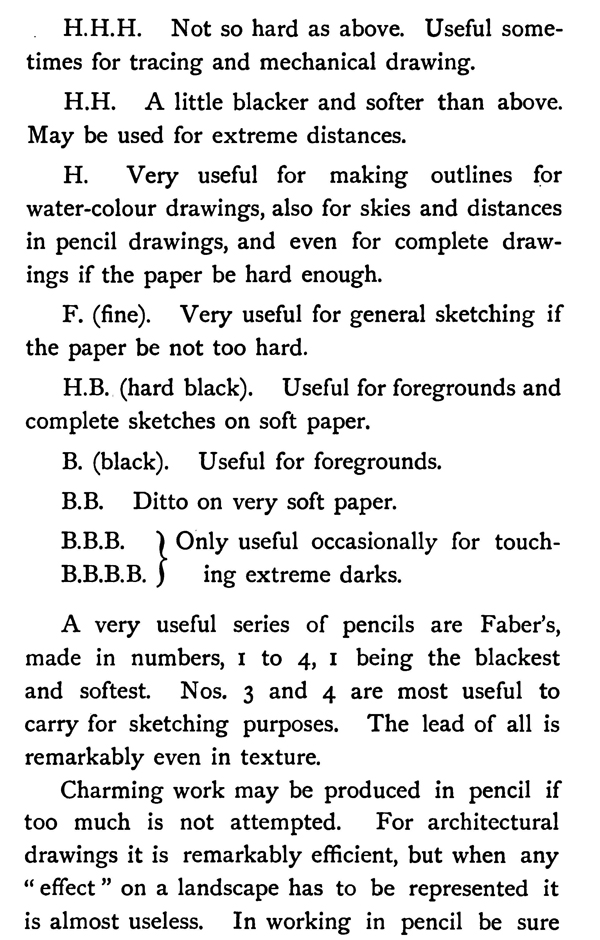

The different qualities usually manufactured are :—

H.H.H.H. (the hardest and purest made). Only useful for mechanical drawing of the finest description.

H.H.H. Not so hard as above. Useful sometimes for tracing and mechanical drawing.

H.H. A little blacker and softer than above. May be used for extreme distances.

H. Very useful for making outlines for water-colour drawings, also for skies and distances in pencil drawings, and even forcomplete drawings if the paper be hard enough.

F. (fine). Very useful for general sketching if the paper be not too hard.

H.B. (hard black). Useful for foregrounds and complete sketches on soft paper.

B. (black). Useful for foregrounds. B.B. Ditto on very soft paper.

B.B.B.) useful occasionally for touch-

B.B.B.B. ing extreme darks.

A very useful series of pencils are Faber's, made in numbers, x to 4, 1 being the blackest and softest. Nos. 3 and 4 are most useful to carry for sketching purposes. The lead of all is remarkably even in texture.

Charming work may be produced in pencil if too much is not attempted. For architectural drawings it is remarkably efficient, but when any " effect " on a landscape has to be represented it is almost useless. In working in pencil be sure and keep the lines firm and sharp. Directly rubbing or a stump is employed all the beauty of the pencil-work vanishes.

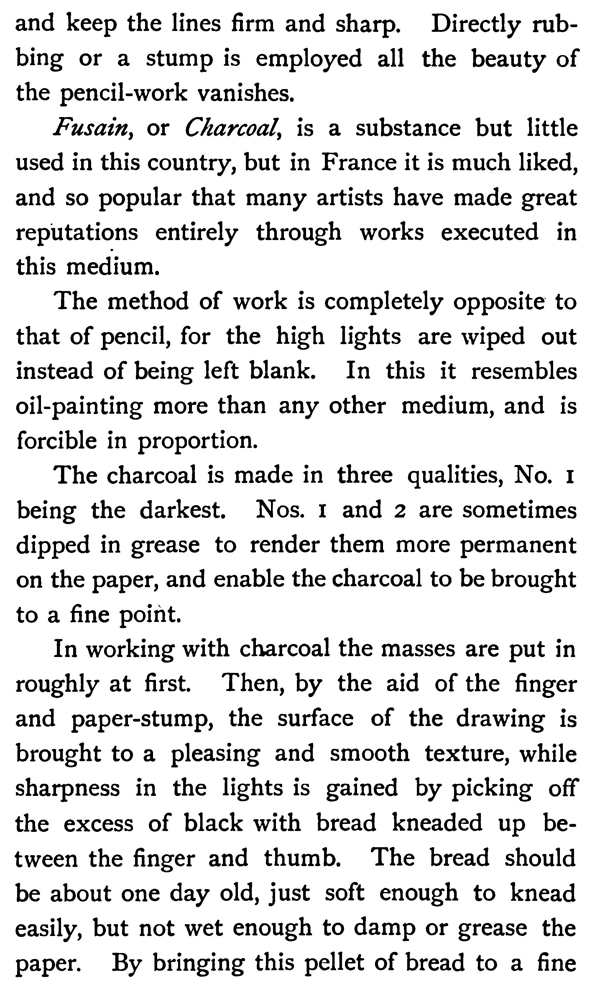

Fusain, or Charcoal, is a substance but little used in this country, but in France it is much liked, and so popular that many artists have made great reputations entirely through works executed in this medium.

The method of work is completely opposite to that of pencil, for the high lights are wiped out instead of being left blank. In this it resembles oil-painting more than any other medium, and is forcible in proportion.

The charcoal is made in three qualities, No. being the darkest. Nos. i and 2 are sometimes dipped in grease to render them more permanent on the paper, and enable the charcoal to be brought to a fine point.

In working with charcoal the masses are put in roughly at first. Then, by the aid of the finger and paper-stump, the surface of the drawing is brought to a pleasing and smooth texture, while sharpness in the lights is gained by picking off the excess of black with bread kneaded up between the finger and thumb. The bread should be about one day old, just soft enough to knead easily, but not wet enough to damp or grease the paper. By bringing this pellet of bread to a fine point the smallest lights can be picked out with the greatest precision and delicacy.

It is best to begin by rubbing charcoal with the finger over the whole of the paper, sufficiently dark to form the sky. Trees, houses, etc., should then be rubbed in, roughly as regards form, but carefully as regards their relative depth of tone to the sky. A white cow in the foreground should be left whiter than the sky, while the dark trees behind should be made as dark as is possible.

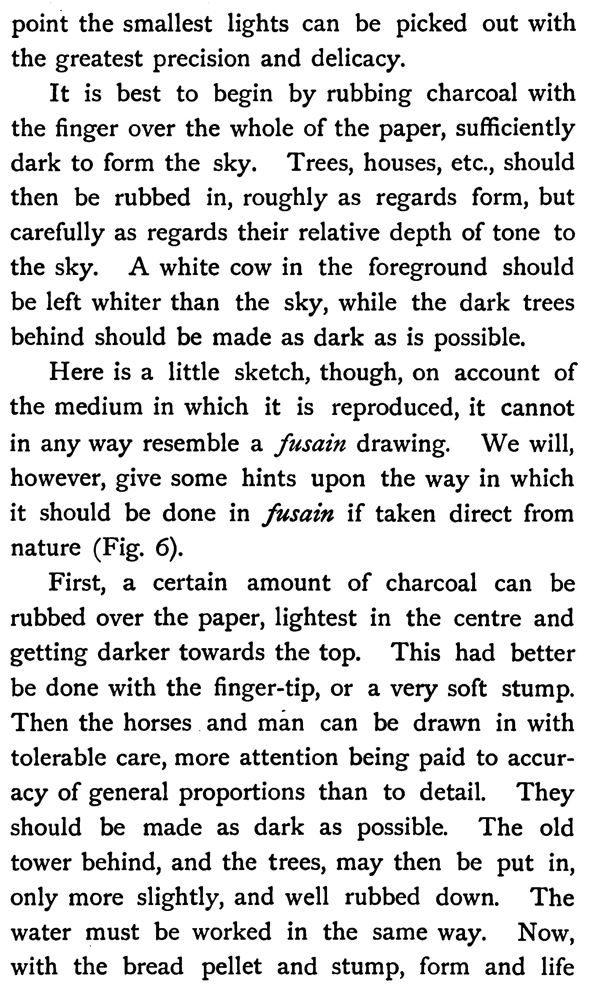

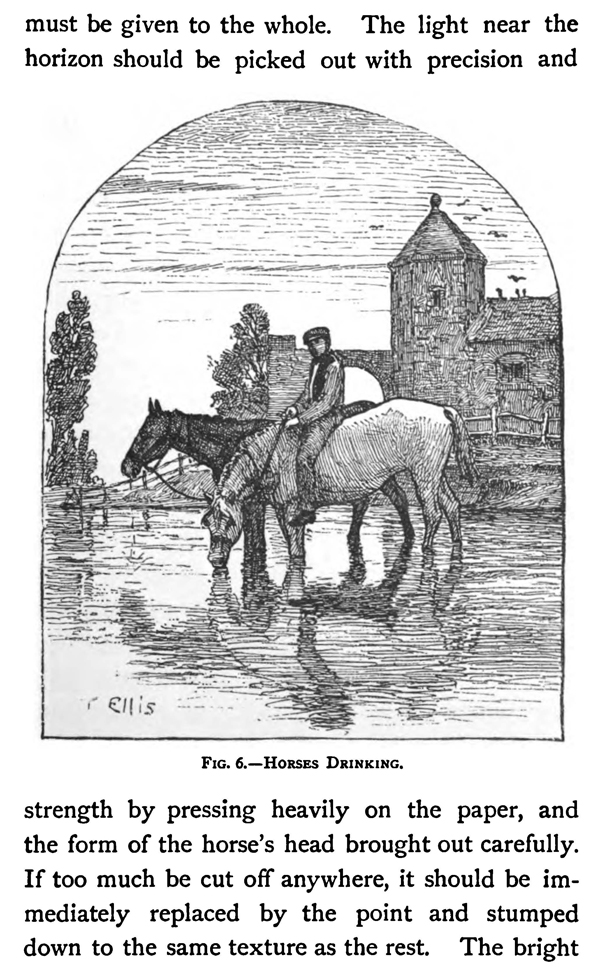

Here is a little sketch, though, on account of the medium in which it is reproduced, it cannot in any way resemble a fusain drawing. We will, however, give some hints upon the way in which it should be done in fusain if taken direct from nature (Fig. 6).

First, a certain amount of charcoal can be rubbed over the paper, lightest in the centre and getting darker towards the top. This had better be done with the finger-tip, or a very soft stump. Then the horses and man can be drawn in with tolerable care, more attention being paid to accuracy of general proportions than to detail. They should be made as dark as possible. The old tower behind, and the trees, may then be put in, only more slightly, and well rubbed down. The water must be worked in the same way.

Now, with the bread pellet and stump, form and life must be given to the whole. The light near the horizon should be picked out

with precision and strength by pressing heavily on the paper, and the form of the horse's head brought out carefully. If too much be cut off anywhere, it should be immediately replaced by the point and stumped down to the same texture as the rest. The bright cloud across the middle of the sky should also be picked out, great care being taken not to make it overlap the old tower or trees. The outline of the tower should be made exact by picking off those parts that in the first drawing have strayed too far, and filling up with stump and point to the true outline. It will be found difficult at first, on account of all this dabbing of the bread pellet, not to make the sky round the trees and tower look spotty ; but by the aid of lightly touching with the pellet those parts that are too dark, and lightly touching with the stump those places that are too pale, perfect evenness of gradation may be obtained. The point, stump, finger, and pellet are used continually ; the point to strengthen, the stump and finger to soften and give texture, and the pellet to lighten—till the whole picture is brought into shape. The final darks in the foreground should only be put in quite at the end, with Nos. i or 2, and the stump used slightly to give texture. The best stumps are made of paper, of all sizes and qualities of hardness, and are so cheap that, if a little worn or loose, they may be thrown away without compunction.

When finished, the drawing must be fixed at once, as the slightest touch will spoil it. An ordinary scent-vapouriser can be used to distribute a liquid called " fz:ratif" evenly over the surface, and the drawing is rendered permanent. "Fixatif" may be bought at any artist's colourman selling French materials, or may easily be made by dissolving one part hard white spirit varnish to seven parts alcohol.

It is very good practice to try and make an even tint on a piece of paper within a space fixed by hard lines. It matters little what form this space takes, a circle, oval, square, or trapezium, but it should have distinct edges, and the tint should be brought up to them sharply. When, by the means above alluded to of darkening the lights and lightening the darker spots, a perfectly even tint seems to have been obtained when seen at the ordinary working distance on a table (about twelve inches) from the eye ; then hold up your paper at least two feet off. To your surprise you will discover many unevennesses of a larger kind that you had been blind to before. These again correct, still keeping your paper far off, till perfect evenness is obtained. This exercise completed a few times will give great power to your hand and eye. It seems wonderful that such a beautiful and facile mode of representation should find so few exponents in England. The only drawback to it is that the sketch or drawing must be fixed out of doors on the spot, or very carefully protected even from wind, and this involves a certain amount of trouble. For studying relative values fusain is perhaps the best medium extant, and is even preferable to chalk, which will be next considered.

Drawing in black or red chalk is much more common here than fusain, and is delightful for studying the figure, but for sketching from nature it is not to be compared with charcoal. Chalk is now but rarely used, except in the same manner as pencil. It can be rubbed, stumped, and picked out in a similar manner to fusain, but is much more difficult to work in, and cannot be recommended for use in sketching from nature.

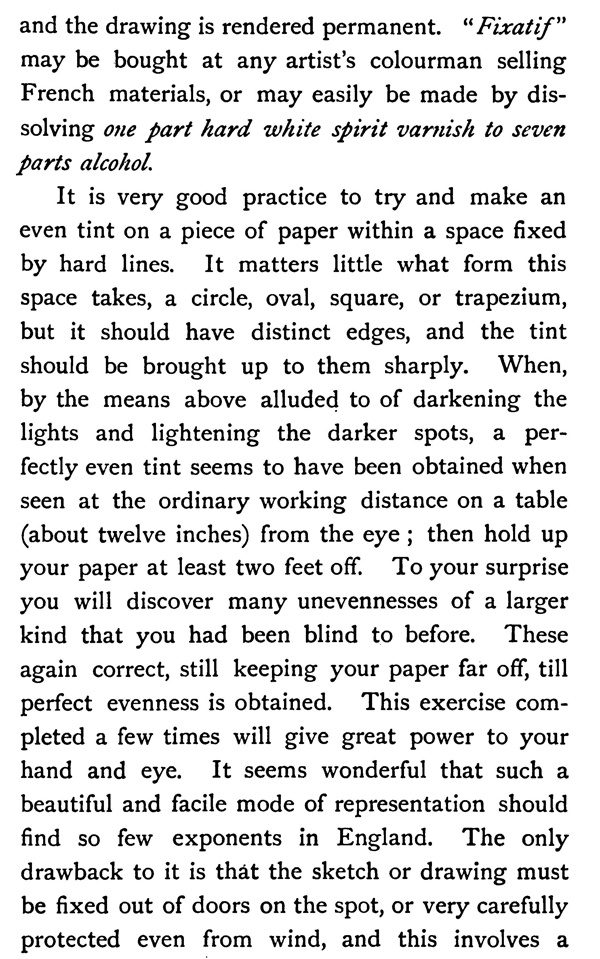

Etching from nature is the last of the black and white media that will be here 17: touched upon. It is very important, as not only beautiful effects may be obtained, but they may be reproduced in great numbers by printing.

The materials requisite are—

A copper plate. (Always obtain the best quality only.)

A dabber of silk or kid.

A ball of etching-ground.

Coarse and fine etching needles.

A mirror is essential for etching buildings or any places where it is desired they should print the right way, i.e. that they should be drawn the reverse of nature on the copper-plate. It will be found convenient to have a shallow box made, into the bottom of which the copper-plate can slide. The hand should rest upon a stiff flat ruler that is kept off the copper by the sides of the box. The mirror can be most easily fastened in the lid of the box, and pivoted vertically, so that by rotating it, and also opening the lid by the hinges, any desired spot may be reflected at one side and rather behind the artist. He should of course sit with his back nearly turned towards his subject. This has its inconveniences, for when an artist etches from nature spectators generally come up behind him, so as not to inconvenience him, as they believe, whereas they really and most effectually cut off his view. For trees, etc., the mirror is unnecessary.

Preparing Plate.—The plate is held between the jaws of a hand-vice, and if of small size is most easily heated by being held over a gas or petroleum stove. The ball of etching-ground must be dabbed occasionally on the top till its substance begins to come off freely, then it must be rubbed rapidly over, and the plate should be taken off before the ground commences to smoke. The whole surface should then be strongly pounded with the silk dabber till it becomes of one uniform brown shiny tint. Before it has time to cool it has to be passed backwards and forwards over a smoking flame, either of a petroleum lamp or wax taper, very carefully, so that the black deposit from the smoke forms evenly and sufficiently quickly to prevent the flame from burning the film. The blackened plate is then ready for use.

It will sometimes be found convenient, if the subject has to be reversed, to sketch it carefully in pencil, and then reverse it on to the plate with tracing paper that has been rubbed over with some white chalk. The outlines should be then drawn in carefully by the point with a firm hand, those of the sky just hard enough to make sure that it is in actual contact with the copper. This can easily be felt. There is a slight but pleasant resistance to the movement of the hand. The point must not be allowed to slide on the surface of the copper, or most probably the " ground " will not be completely cut through, and an interrupted and shaky line will result. For the foreground objects the point should be dug into the copper as deeply as is compatible with retaining the power of making the lines free and bold, for this is the great advantage etching possesses over line engravings. Never lose sight of this quality of freedom, but do not let your drawing be loose and careless, for a single careless stroke in etching stands out in a staring way that is not known in a pencil, pen-and-ink, or fusain drawing. Even there it is bad enough, but it is not perpetuated by endless copies as in an etching. Always bear in mind that you are not working for a single copy but for a thousand, and try and put into it a thousand times more art and care than into your single pen-and-ink drawing.

In etching from nature it is almost impossible to obtain an elaborate effect. A finished sketch should be aimed at, and each stroke of the point should be made to represent as much as possible.

When every intended line of the work is complete, and after the back of the copper-plate has been protected by Brunswick black or some varnish, the plate may be put into the acid bath. The bath may be of varying strengths, and a convenient one is obtained by taking equal parts of commercial nitric acid (sp. gr. •32) and ordinary water. A little old liquid left from previous bitings should be added, or a few scraps of copper, to take off the first edge of its strength, as otherwise it will commence by biting too quickly. When all the lines have been bitten deeply enough for the extreme distance, the plate must be taken out, dried with blotting-paper, and the distance carefully painted over with " stopping-out " varnish ; and when thoroughly dry it should be returned to the bath, that the lines intended to be stronger may be bitten more. By successively stopping-out and biting a great deal of gradation may be given to the lines. The exact amount necessary can only be found out by experience ; but some idea of the depth of the lines can be obtained by feeling with the point, and if the acid is of the strength mentioned above, two minutes for the extreme distance and half an hour for the added bitings of the foreground lines, may be allowed. The temperature of the air is here taken to be about 6o°, but if higher this exposure will be too long, and if lower it will not be long enough. A very little difference of temperature makes a great deal of difference in the biting. The plate may be cleaned with benzine, petroleum, or turpentine.

Many artists prefer etching with very weak acid when the plate is in the bath. The foreground should then be commenced first, and the extreme distance last, so that by the time the distance is finished the foreground should be sufficiently bitten to be dark enough to come well forward. It is only by the various thickness of the lines that the effect of distance or nearness is given. The difference of thickness in the lines between the distance and foreground should be very great, much more than is necessary in a pencil sketch, for the printing nearly always levels the strength of effect. A skilful printer, however, is able to make a great deal out of a plate, by leaving or taking the ink film from its surface at his own discretion ; yet in that case it is the printer and not the etcher who is the artist.

The " biting" with acid had better be done indoors, and the " stopping-out " should be done as much as possible on the ground, and in presence of nature ; for the etcher is then better able to see what parts will require to be least bitten, and he is also sure to add good work to his plate every time he takes it to the ground.

It is impossible to give other than the most meagre outline of the process of etching in this place. Lalanne's beautiful little book, translated into English (which can be obtained through any artists' colourman), will be found to do full justice to this exquisite art.

Privacy Policy ..... Contact Us