Home > Directory of Drawing Lessons > Art Principles & Elements > Art Composition > Pictorial Composition and the Arrangement of Objects

How to Create Beautiful Pictorial Compositions with the Following Lessons for Arranging Elements in Your Drawings

|

|

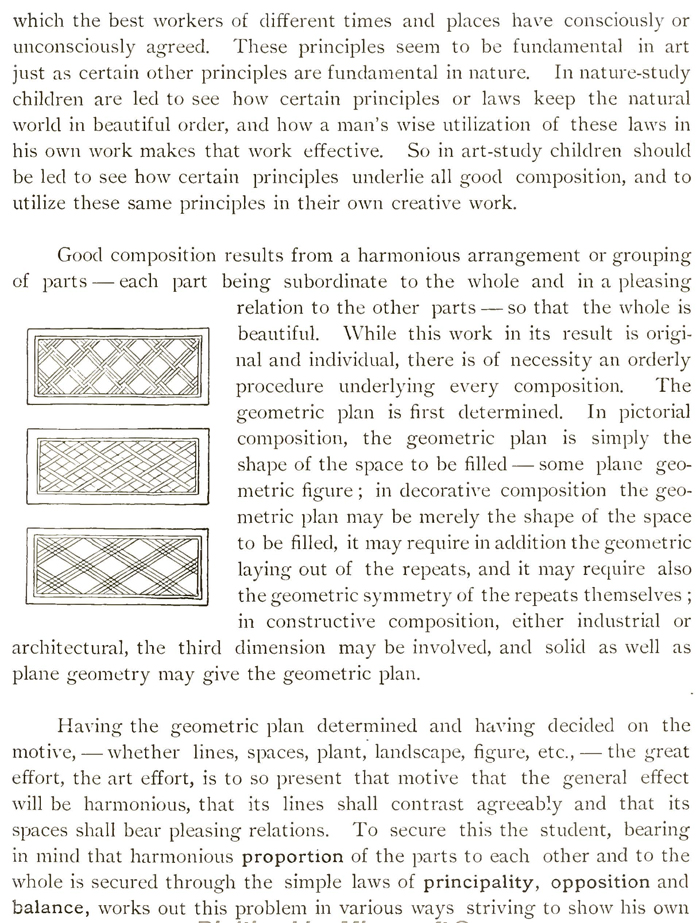

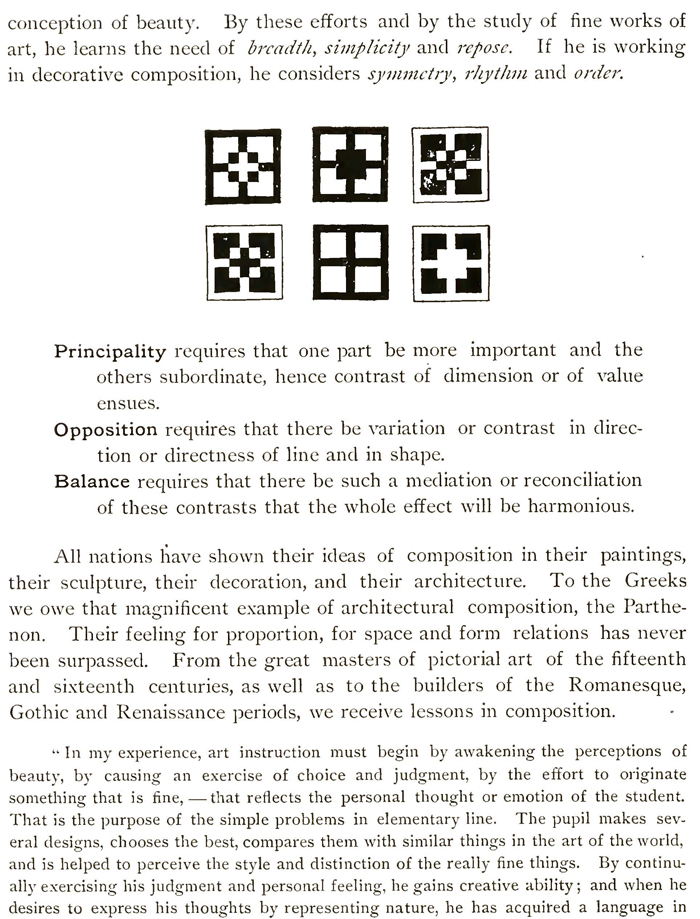

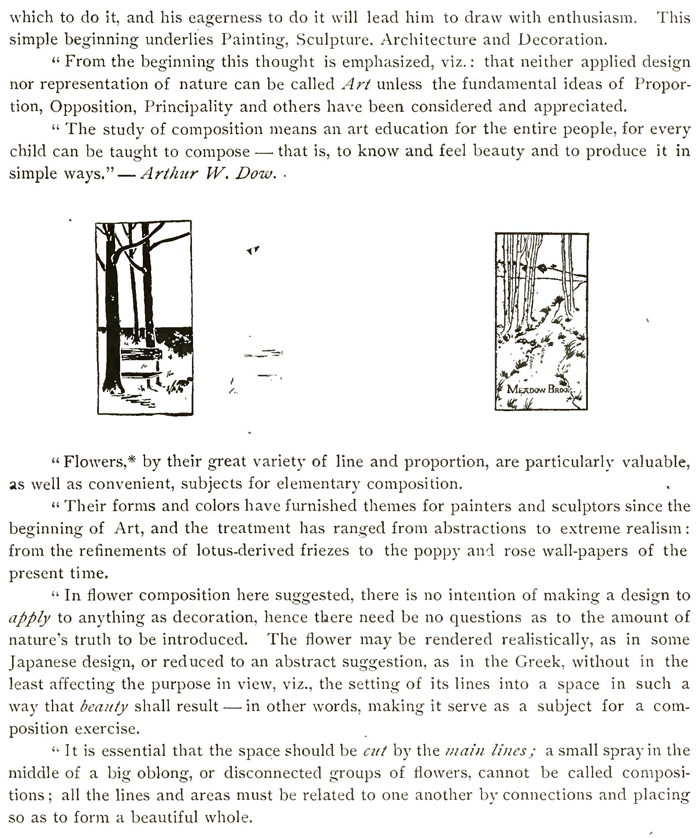

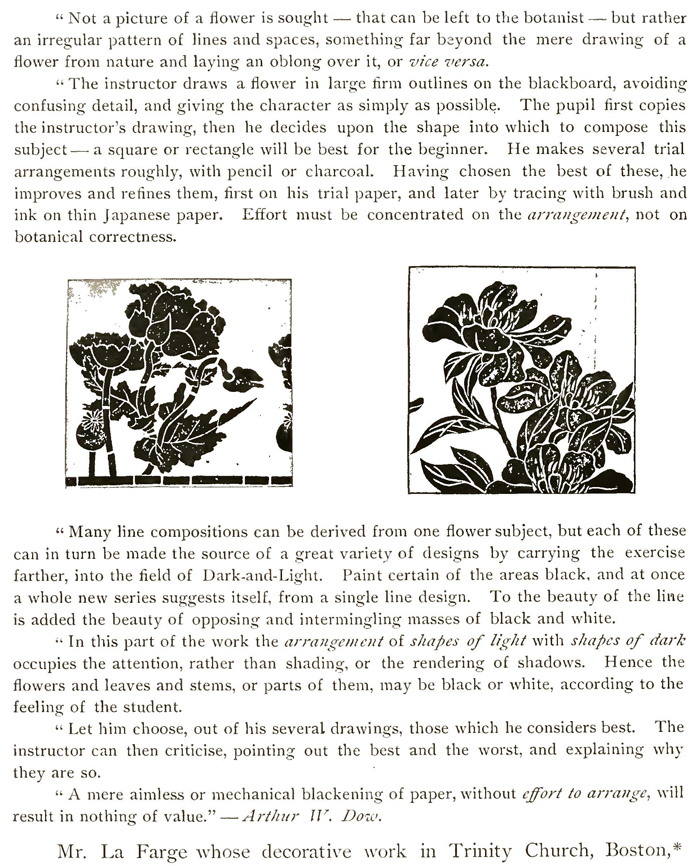

The text above is made up of images, if you need to copy any text, you can find it below. Thank you. Representation or Drawing as Applied in Representing the Appearance of ObjectsRepresentation deals not only with the truth of appearance; it also required the making of a picture by composition as well as by drawing. The art principles of selection and arrangement can be applied in elementary composition by the pupils, not only in the selection and grouping of objects to make a picture, but also in selection and arrangement in landscape. Here space relations and ine direction play important roles. It must be remembered that composition appeals directly to the creative faculty. What a Picture is.A true picture shows not only how an object or a group of objects appears, but it tells also something of the one who has drawn the picture. It tells how the objects looked to him ; it tells not only what he saw, but also what he thought about the objects. For whoever draws a picture indicates, or tries to indicate, in the drawing what parts he cared for most. He also endeavors to show his ideas of beautiful composition. This human element, added to the true presentation of the appearance of objects, makes the real picture. Now a picture may be in outline, in light and dark, in light and shade, or in color. The study and drawing of the appearance of simple models and objects for the mere outline is valuable in order to attain a realization of the true appearance in different positions. Along with this, there should be a study of the best methods of expressing the relative importance of objects, of showing the greatest beauty of contour and of light and shade, and of giving feeling to the work by drawing; also of suggesting color through light and dark by " pencil-painting" or by ink and the brush, or by painting with color. PICTORIAL COMPOSITION.Its Purpose.One of the most important elements in Representation is that of composition. This element enters into all Representation, whether of single objects or a group of objects. Its purpose is to create a subtile arrangement or synthesis of lines, of forms, of colors, which shall present a beautiful whole. The final test of composition must be its effect in producing a beautiful impression as a whole—an impression attained only through that interrelation and subordination of parts which makes oneness—unity. Ruskin defines composition as "the help of everything in the oictui-e by everything else." The first step toward composition is selection, looking toward harmony. The objects selected for a group may be beautiful. in themselves, and yet, if their relation to each other, if their mutual "help" is not considered, if, in other words, they are not "composed," the effect as a whole will not be beautiful. Selection of Objects. It is well to remember that even in its beginnings this work should be pictorial art. For this purpose, select objects which are beautiful in form and pleasing in association. The many pleasant associations that we have with objects which are constant companions form a good basis for direct study. A Group.In making a group, determine first the idea to be expressed, thus leading to the selection of objects having harmonious relations. The idea of the group, then, controls the selection of the objects —here again appears the maxim, as true in art as in education, the whole before the parts. If the idea is to express the beauty of fruit, let the group be wholly of fruit. If the idea is to express the beauty of vegetables —fruits of the earth — let the group he wholly of vegetables. A variety of things having no apparent connection with one another gives no pleasure in a picture, and distracts rather than composes. For instance, a group of delicate fruit with rougher vegetables seem inharmoni. ous. They have not enough in common, either in the purpose which they serve or in their general. appearance. The arrangement is incongruous. Only the most hardy fruit should be grouped with vegetables. The Arrangement of a Group.If a picture of a group is desired, it will not, then, he satisfactory to place the objects at random and draw them. Some thought must be given to the arrangement ; for, if arranged in one way, the group may be very pleasing, while if arranged differently, the group may not be at all pleasing. If such arrangements are considered thoughtfully, it will be found that, in the one case, the simple principles of elementary composition have been regarded, and in the other they have been disregarded. It will be found, moreover, that these principles of composition are so simple and natural that children may be led to discover them. In studying the arrangement of a group, consider,— 1. The place of the principal object. (1) Choose the principal object, and, generally, place it centrally but not exactly in the centre ; (2) do not place the other objects in a straight line with the principal object ; (3) try the effect of placing the objects so that if the centres of their bases were connected an irregular figure would be made ; (4), place them as if they were good friends and belonged together, and (5) so that they will appear at rest. But remember (6) that the objects should not have the same positions, that is, their axes should not be all upright or all horizontal ; they should not be parallel or at right angles to each other; and they should not present exactly the same faces ; and (7) one of the objects should be partially hidden behind another, even if there are no more than two objects in the group. Look now (8) to see if, in the group that you have made, the objects will appear of the same height when drawn. If so, change them, for the effect will not be pleasing. By skilful questioning, the pupils can be led to these points. It will be noticed that unity, repose and variety are emphasized as of particular importance. They are indeed essentials in all good pictorial composition. Both variety and repose should be tributary to unity in any composition. Where unity is lacking, repose is always lacking. Consider also the arrangement with reference to carrying the eye into the picture. Placing one object farther back than another suggests distance into the picture, which is always pleasing, as it brings with it the feeling of freedom and atmosphere. If one of the objects is placed so that its axis or its leading lines tend from you, it will aid in producing the effect of distance. And as a test of the whole, consider the general space relations. This may be shown in a very satisfactory way by enclosing the group, as it were, by observing it through an oblong opening cut in paper, which will make a frame for the group. The hands held first vertically and then horizontally also suggest a frame. PLACING.Placing Objects or Groups.Thought should be given to the placing of the various sprays, objects or groups, so that they may be advantageously seen. It is always better for a pupil to draw from an object or group on some desk other than his own, to get the softening and unifying effect of distance : and frequently it is well that the object or group drawn should be at considerable distance. After the objects or groups arc placed, let each pupil look about the room to find that which he likes the best and which he can see in its best position ; for art seeks for the best. The placing of objects is generally something of a problem. But in the case of an upright cylindric or conic object, which always appears the same, the solution is easy. Boards may be procured long enough to extend across the aisles between the desks. Two such hoards would be required for each alternate aisle, one being needed at the front and one half-way down the aisle. Cleats may be screwed on the ends of the boxes of the desk to serve as supports for these boards when they are needed for the drawing exercise. The other aisles will be left free for the teacher or pupils. At the close of the exercise, the boards can be removed and put away. Other models and objects may be arranged on the desks. Each pupil may pile three or four books far back upon the desk, alternately at the left and right. If there is absolutely no level part of the desk, raise the pile by placing a folded paper under the front, so that there may be a surface about level for the models. On the upper book place a sheet of manila paper, and then arrange the models or objects to make a pleasing group. Be careful that the objects are not too far below the eye. If branches are to be drawn they may be hung in various places, so as to give the best opportunity for study to the greatest number. If they are hung on the blackboard for the pupils in the front seats, a piece of white or neutral-tinted paper should be placed behind them. A pasteboard folded like a table picture-frame or an open book standing on a board across the aisle serves very well as a support for a small branch. A spray of leaves or flowers should be studied from all sides to discover its most pleasing aspect. It is well to have a spray placed in a vase of good form ; if that is not practicable, it is frequently possible to keep the spray in good position by placing the end between the leaves of a closed book which is standing. It is well, also, to have the spray at some little distance from the pupil who is drawing it. It may sometimes be desirable to remove part of the stem or a leaf or two, or perhaps to add another spray in order to get a good effect. The Japanese make the arrangement of leaves and flowers a very serious study. There is an interesting book by Conder on this Japanese art. Composition.COMPOSITION, as the work is used in art, is a general term covering the individual worker's choice and arrangement of forms and colors, lines and spaces, in order to perfectly and beautifully express his idea and carry, out his plan. He is continually collecting material for this use, through his studies of nature and of the art productions of his fellow-workers. Through such studies he fills his mind with conceptions of beautiful forms and colors ; he develops judgment regarding the appropriateness of certain forms, colors, plans and arrangements to certain ideas of use and beauty; and he cultivates his power of idealizing familiar things and their relations to each other. It is when he himself composes a bit of Representation or Decoration or Construction that he begins to make truly creative use of what he has acquired in other lines of his art study. Composition, in a word, stands for individuality in art. Composition as a feature of art instruction stands for the development of individual creative power in the art activities. A study of good composition already existing in the various departments of art shows that there are a few great, underlying principles on which the best workers of different times and places have consciously or unconsciously agreed. These principles seem to be fundamental in art just as certain other principles are fundamental in nature. In nature-study children are led to see how certain principles or laws keep the natural world in beautiful order, and how a man's wise utilization of these laws in his own work makes that work effective. So in art-study children should be led to see how certain principles underlie all good composition, and to utilize these same principles in their own creative work. Good composition results from a harmonious arrangement or grouping of parts — each part being subordinate to the whole and in a pleasing relation to the other parts — so that the whole is beautiful. While this work in its result is original and individual, there is of necessity an orderly procedure underlying every composition. The geometric plan is first determined. In pictorial composition, the geometric plan is simply the shape of the space to be filled — some plane geometric figure ; in decorative composition the geometric plan may be merely the shape of the space to be filled, it may require in addition the geometric laying out of the repeats, and it may require also the geometric symmetry of the repeats themselves ; in constructive composition, either industrial or architectural, the third dimension may be involved, and solid as well as plane geometry may give the geometric plan. Having the geometric plan determined and having decided on the motive, — whether lines, spaces, plant, landscape, figure, etc., — the great effort, the art effort, is to so present that motive that the general effect will be harmonious, that its lines shall contrast agreeably and that its spaces shall bear pleasing relations. To secure this the student, bearing in mind that harmonious proportion of the parts to each other and to the whole is secured through the simple laws of principality, opposition and balance, works out this problem in various ways striving to show his own conception of beauty. By these efforts and by the study of fine works of art, he learns the need of breadth, simplicity and repose. If he is working in decorative composition, he considers symmetty, rhythm and order. Principality requires that one part be more important and the others subordinate, hence contrast of dimension or of value ensues. Opposition requires that there be variation or contrast in direction or directness of line and in shape. Balance requires that there be such a mediation or reconciliation of these contrasts that the whole effect will be harmonious. All nations have shown their ideas of composition in their paintings, their sculpture, their decoration, and their architecture. To the Greeks we owe that magnificent example of architectural composition, the Parthenon. Their feeling for proportion, for space and form relations has never been surpassed. From the great masters of pictorial art of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, as well as to the builders of the Romanesque, Gothic and Renaissance periods, we receive lessons in composition. In my experience, art instruction must begin by awakening the perceptions of beauty, by causing an exercise of choice and judgment, by the effort to originate something that is fine, —that reflects the personal thought or emotion of the student. That is the purpose of the simple problems in elementary line. The pupil makes several designs, chooses the best, compares them with similar things in the art of the world, and is helped to perceive the style and distinction of the really fine things. By continually exercising his judgment and personal feeling, he gains creative ability; and when he desires to express his thoughts by representing nature, he has acquired a language in which to do it, and his eagerness to do it will lead him to draw with enthusiasm. This simple beginning underlies Painting, Sculpture, Architecture and Decoration. " From the beginning this thought is emphasized : that neither applied design nor representation of nature can be called Art unless the fundamental ideas of Proportion, Opposition, Principality and others have been considered and appreciated." " The study of composition means an art education for the entire people, for every child can be taught to compose — that is, to know and feel beauty and to produce it in simple ways."— Arthur W. Dow." "Flowers, by their great variety of line and proportion, are particularly valuable, as well as convenient, subjects for elementary composition." " Their forms and colors have furnished themes for painters and sculptors since the beginning of Art, and the treatment has ranged from abstractions to extreme realism : from the refinements of lotus-derived friezes to the poppy and rose wall-papers of the present time. In flower composition here suggested, there is no intention of making a design to 7,Pft ly to anything as decoration, hence there need be no questions as to the amount of nature's truth to be introduced. The flower may be rendered realistically, as in some Japanese design, or reduced to an abstract suggestion, as in the Greek, without in the least affecting the purpose in view, viz., the setting of its lines into a space in such a way that beauty shall result — in other words, making it serve as a subject for a composition exercise. It is essential that the space should be cut by the main lines; a small spray in the middle of a big oblong, or disconnected groups of flowers, cannot be called compositions ; all the lines and areas must be related to one another by connections and placing so as to form a beautiful whole." " Not a picture of a flower is sought — that can be left to the botanist — but rather an irregular pattern of lines and spaces, something far bayond the mere drawing of a flower from nature and laying an oblong over it, or vice versa." " The instructor draws a flower in large firm outlines on the blackboard, avoiding confusing detail, and giving the character as simply as possible. The pupil first copies the instructor's drawing, then he decides upon the shape into which to compose this subject— a square or rectangle will be best for the beginner. He makes several trial arrangements roughly, with pencil or charcoal. Having chosen the best of these, he improves and refines them, first on his trial paper, and later by tracing with brush and ink on thin Japanese paper. Effort must be concentrated on the arrangement, not on botanical correctness." " Many line compositions can be derived from one flower subject, but each of these can in turn be made the source of a great variety of designs by carrying the exercise farther, into the field of Dark-and-Light. Paint certain of the areas black, and at once a whole new series suggests itself, from a single line design. To the beauty of the line is added the beauty of opposing and intermingling masses of black and white." " In this part of the work the arrangement of shapes of light with shafies of dark occupies the attention, rather than shading, or the rendering of shadows. Hence the flowers and leaves and stems, or parts of them, may be black or white, according to the feeling of the student." " Let him choose, out of his several drawings, those which he considers best. The instructor can then criticise, pointing out the best and the worst, and explaining why they are so." " A mere aimless or mechanical blackening of paper, without effort to arrange, will result in nothing of value."— Arthur 717. Dow. Mr. La Farge whose decorative work in Trinity Church, Boston, whose stained-glass and whose general composition show the finest feeling for proportion and spacing, writes of art in "Letters from Japan." " I have far within me a belief that art is the love of certain balanced proportions and relations which the mind likes to discover and to bring out in what it deals with, be it thought or the actions of men, or the influences of nature, or the material things in which necessity makes it to work. I should then expand this idea until it stretched from the patterns of earliest pottery to the harmony of the lines of Homer. Then I should say that in our plastic arts the relations of lines and spaces are, in my belief, the first and earliest desires. And again I should have to say that, in my unexpressed faith, these needs are as needs of the soul, and echoes of the laws of the universe, seen and unseen, reflections of the universal mathematics, cadences of the ancient music of the spheres." "For I am forced to believe that there are laws for our eyes as well as for our ears, and that when, if ever, these shall have been deciphered, as has been the good fortune with music, then shall we find that all the best artists have carefully preserved their instinctive obedience to these, and have all cared together for this before all." " For the arrangements of line and balances of spaces which meet these underlying needs are indeed the points through which we recognize the answer to our natural love and sensitiveness for order, and through this answer we feel, clearly or obscurely, the difference between what we call great men and what we call the average, whatever the personal charm may be." " This is why we remember so easily the arrangement and composition of such a one whom we call a master — that is why the silhouette' of a Millet against the sky, why his placing of outlines within the rectangle of his picture, makes a different, a final, and decisive result, impressed strongly upon the memory which classifies it, when you compare it with the record of the sante story, say, by Jules Breton. It is not the difference of the fact in nature, it is not that the latter artist is not in love with his subject, that he has not a poetic nature, that he is not simple, that he has not dignity. that he is not exquisite; it is that he has not found in nature of his own instinct the eternal mathematics which accompany facts of sight. For indeed, to use other words, in what does one differ from the other ? The arrangement of the idea or subject may be the same, the costume, the landscape, the time of day, nay, the very person represented. But the Millet, if we take this instance, is framed within a larger line, its spaces are of greater or more subtle ponderation, its building together more architectural. That is to say, all its spaces are more surely related to one another and not only to the story told nor only to the accidental occurrence of the same. The eternal has been brought in to sustain the transient. . . ." "Yes, the mere direction or distance of a line by the variation of some fraction of an inch establishes this enormous superiority — a little more curve or less, a mere black or white or colored space of a certain proportion, a few darks or reds or blues. And

now you will ask, Do you intend to state that decoration —? To which I should say, I do not mean to leave my main path of principles to-day, and when I return we shall have time to discuss objections. Besides, I am not arguing; I am telling you.'" — John La Farge.

|

Privacy Policy ...... Contact Us