Home > Directory of Drawing Lesson > Drawing People > Introduction to Figure Drawing

Introduction to Figure Drawing : Drawing People Lessons for Beginners |

|

The text above is made up of images, so, if you need to copy any of the text for a school assignment, please copy some of the text below.

DRAWING THE HUMAN FIGURE - AN INTRODUCTION TO DRAWING PEOPLE

Students usually pass through the antique before being promoted to the life class. It is held that by working from casts they have time to gain facility in method, and also some knowledge of human proportions, both' very needful, before attacking the living figure.

That this latter study requires all the equipment the student can command need not be questioned, but though young students may not be able to use their materials skillfully, and may not have a keen sense of proportion, they are familiar with the living figure, for they are human themselves, and acquainted in a practical way with their own structure.

On the other hand all art teachers must be aware of the disadvantages of using the antique as a sole means of training. The student cannot see the classical figures as the sculptor created them in marble or bronze, cannot see them as part of an architectural whole, and viewed thus, torn from their past, in the antique classroom, the !dull plaster does not stir his artistic consciousness. He `does not perceive the .subtle variations from the living form, by which the sculptor sought to express his idea of a god-like person. The fine proportions and flow of line escape him, and above all the statues stand so quietly that he finds himself quietening in his attack ; he involuntarily slows down and loses that touch of fever which counts for so much in the study of drawing.

In ordinary school life educationists postpone an abstract study like grammar until the child mind has developed sufficiently to take interest in the train of thought. So it is with art students, who, after working from the living model, willingly turn to the antique, and study it with more profit and more enthusiasm for its noble qualities than would have been possible to them coming to it without preparation. The problems of the human figure they now see presented in typical form, and they recognize a canon of proportion which they can more readily grasp, after having observed the great variations in a series of living models.

Coming now to the study of the living figure, the student should understand that a great deal more than mere copying is implied, for it embodies many aspects of art study, spacing, composition, structure, and especially proportion.

There are certain difficulties which will surely meet the beginner, and these it may be well to discuss. First the anthropomorphic attitude of mind on the part of the student already referred to must be combated by the teacher. The former is likely to be obsessed by the figure before him to the extent that the necessity for imitation seems all important. The drawing, he thinks, must be made as like the figure as possible. In other words the student's power of selection is dormant. There are so many things to be attended to that the drawing is apt to be a mere assembling of members, trunk, limbs, etc., to say nothing of details such as fingers and toe-nails.

The teacher, therefore, has to point out the aims of drawing from the figure. These are not necessarily to recreate a material person by the accumulation of parts, and especially not to emphasize the nakedness of the figure, as beginners are prone to do. The figure is selected as a special subject of study because the nude form presents problems of line and structure more 'directly and trenchantly than any other material which can be set before him.

What should the teacher emphasize as the first step in studying the living figure ? The answer may be given in a word—movement! The living figure is posing in a state of suspended animation, and a sense of movement there must be in any position of the figure. Either the movement has preceded the pose, or the latter is about to pass into action.

Beginners are often oblivious of this sense of arrested movement. Their figures are lumpy and stiff, and they rarely or never give as much action as the figure displays. If, say, the torso leans, they diminish the amount of inclination so that the figure seems to be sitting upright, or nearly so. Especially is this seen in the pose of the head, which often inclines in order to balance an obliquity of the torso or limbs. The novice rarely sees this. To him all heads are upright at attention. It may be said here that what the student suffers from in every branch of ;drawing is not, as he supposes, an unskilled hand, but an untrained eye. The teacher's efforts are constantly directed to the development of the visual faculty, the power of analyzing, judging inclinations, measuring proportions, finding the lines which indicate the structure, in all of which the eye needs to be trained. Cleverness, a kind of juggling, which produces effects akin to the lightning sketches at an entertainment, may be deemed essential by an indiscriminating public, but such ideas must be gently laughed out of a school of art, if they ever find utterance there.

It is to the eye then that the main course of direction and criticism should be directed. Even plumbing and measuring should be used only as a secondary aid, to corroborate criticism, for if these mechanical aids are employed too freely, the eye suffers and loses self-reliance.

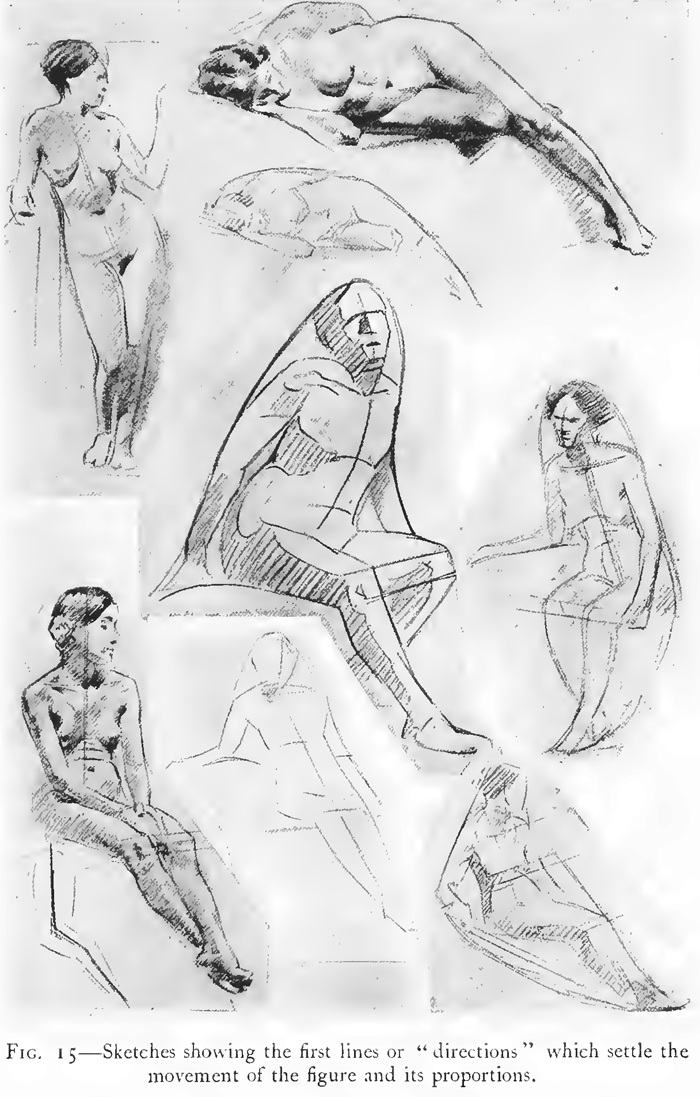

Coming to the question of movement we realize at once that it is represented through direction. All figures, torsos or limbs have a general direction, and these inclinations can be suggested by lines. A seated figure can be represented in direction by three lines. (FIG. 15.) Students unwilling to commence a study with such simple preparation generally show in their work a lack of vitality and movement ; they begin by seizing on the forms, and consequently the general idea escapes them. The mischief occurs at the commencement of the drawing. No amount of delicate detail, if it be drawn piecemeal, will compensate for the lack of intelligent construction. The whole figure should be surveyed at the outset. Too often the eye wanders round .the contours, with the result that the drawing lacks proportion and movement.

FIG. 16—Sketches showing the first lines or " directions" which settle the movement of the figure and its proportions.

FIG. 16—A drawing made with charcoal on Michallet. The appearance of weight and solidity is due as much to the quality of the line as to the shading.

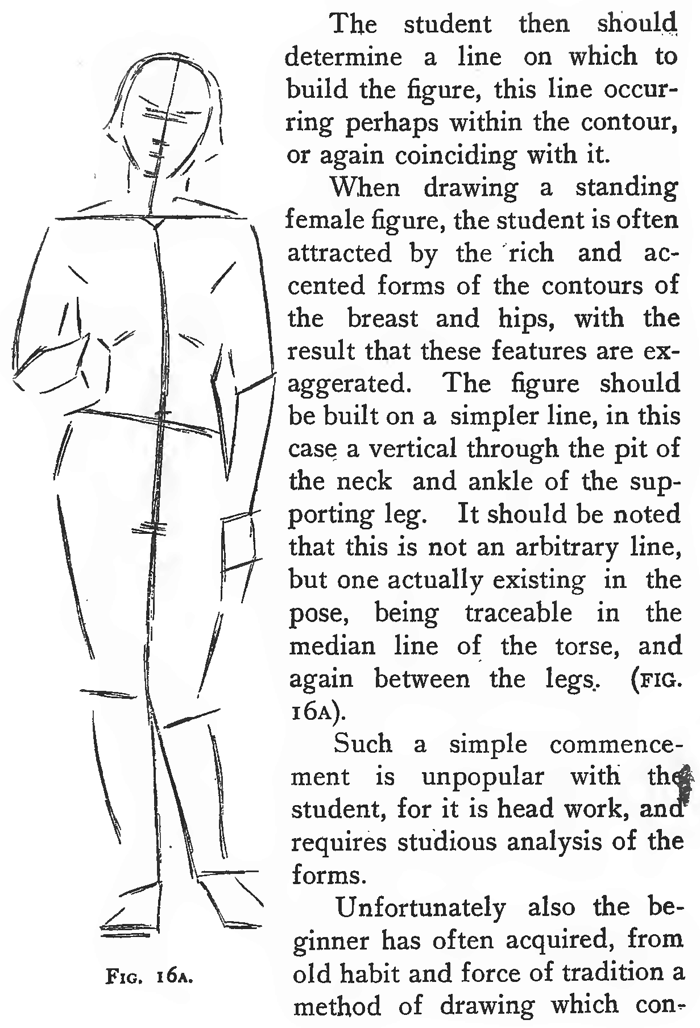

The student then should determine a line on which to build the figure, this line occurring perhaps within the contour, or again coinciding with it.

When drawing a standing female figure, the student is often attracted by the -rich and accented forms of the contours of the breast and hips, with the result that these features are exaggerated. The figure should be built on a simpler line, in this case a vertical through the pit of the neck and ankle of the supporting leg. It should be noted that this is not an arbitrary line, but one actually existing in the pose, being traceable in the median line of the torso, and again between the legs.

Such a simple commencement is unpopular with the student, for it is head work, an requires studious analysis of the forms.

Unfortunately also the beginner has often acquired, from old habit and force of tradition a method of drawing which consists generally in beginning at the top and descending piecemeal till the feet are reached, that is if there is room for them. Such a vicious method is common even among students possessing great facility. The case may be compared with that of a language student who has never heard French spoken, and is surprised when his tutor tells him he has a wretched accent, though he is entirely unconscious of having acquired it. Ingres used to say "Don't draw one by one and in succession, the head, then the torso, then the arms, and so forth. If you did you would be bound to fail in reproducing the harmony of the whole effect. Rather set yourself to fix the relative proportions existing between the several parts, and to gain the mastery over the life and motion, and in giving expression to this action, don't be afraid of exaggeration. What you have to fear is luke warmness."

The teacher has another difficulty to face. He should not impose his own way of seeing on his pupils, and thus deprive them of their individuality, nor seek to bias their own self-expression. A student's feeling for form may perchance be somewhat stark, indeed may verge on ugliness, to the point of exaggerating or caricaturing the form, but the wise teacher will be shy of admonishing-such a student, of advising him to look for smoothness,. grace or beauty, because character, individuality and strength may be the chief note in that pupil's future work. There is room in the world of art for all manner of individual expression. The touchstone is whether it is sincere. Imitation, posing, conscious seeking after a style on the part of students cannot be too loudly condemned.

But where the student's work is wanting because of his lack of method or of knowledge of materials, the teacher is on firm ground. The student must be taught everything, even how to hold a pencil or brush. In matters of method and of the use of the implements of his craft, he should put himself entirely in the hands of his teacher, who cannot guide his students unless they trust him.

That introduces the question whether the teacher should work at the model before or with his students, or confine himself entirely to the office of adviser and critic. The exponents of the new modes of teaching, as practiced in junior schools, incline to the latter view. They say that directly a teacher demonstrates before his scholars, he is biasing their vision, is preventing their seeing the object for themselves, and is obtruding his own vision of things to the detriment of their personal expression. This is very true provided that the teacher's inhibition does not extend to method, which, as pointed out above, must be taught; but there is another aspect of the relations between teacher and pupils, an aspect which is of special importance in dealing with art students who are spending all their hours at the same study. They are apt to be discouraged after long toiling, and consequently may be tempted to look upon their teacher as he visits them on his rounds, merely as critic, carper and fault-finder. This is a real danger, and it is in the power of the teacher to overcome it. If he is wise he will regard himself not as one aloof, in another sphere,

that of the professional artist who occasionally condescends to criticize the efforts of the novice, but in the much closer relationship of an elder brother, who is willing to work at the same tasks as his pupils. It is certainly dangerous always to paint and draw before the students, but to work with them occasionally is to exhibit a spirit of comradeship which at once stimulates the class to its best efforts.

Again a student sometimes confesses inability to proceed with an exercise, and if the teacher is convinced that the case is genuine, and works on the drawing, showing in what ways the pupil's vision has fallen short, and giving a demonstration of how far a drawing may be carried, much good may result.

From this it follows that the student should not flag or sulk at the continuance of his task while the teacher is willing to interest himself in it. R. A. M. Stevenson, in his life of Velasquez, has some interesting comments on the methods of the great teacher Carolus Duran, which should be read by all students, weak-kneed or otherwise.

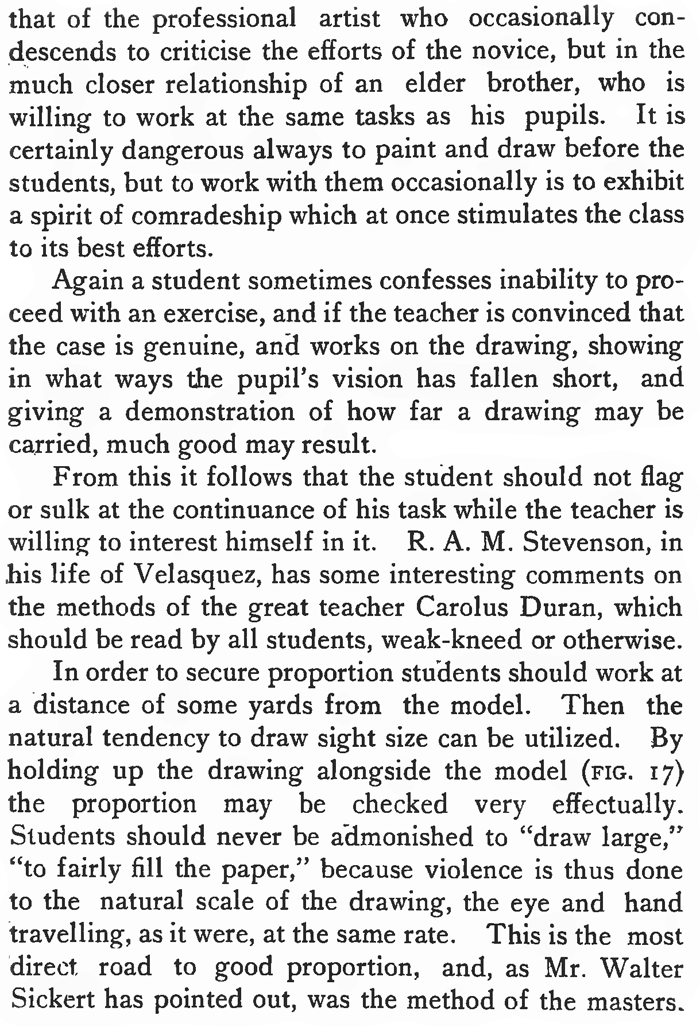

In order to secure proportion students should work at a distance of some yards from the model. Then the natural tendency to draw sight size can be utilized. By holding up the drawing alongside the model (FIG. I 7) the proportion may be checked very effectually. Students should never be admonished to "draw large," "to fairly fill the paper," because violence is thus done to the natural scale of the drawing, the eye and hand traveling, as it were, at the same rate. This is the most direct road to good proportion, and, as Mr. Walter Sickert has pointed out, was the method of the masters.

If the drawing is too small in scale to allow of adequate treatment, the student should go nearer the model or use a finer point.

The drawing should be frequently viewed at arm's length. Students often hold the drawing too close, say that the lower half of the paper is practically out of sight, with a consequent detriment to the proportions.

A few words may be said on the vexed question of backgrounds. Some teachers, in their zeal for complete expression, insist that their students shall indicate the tone of the background, with any accessories that may be present. This it must be contended, is a mistaken view, for backgrounds imply tone study, but drawing from the figure is not merely an exercise in tone; structure, flow of line, composition, etc., demand their share of attention. The student is not concerned with the photographic aspect of the figure, nor is he studying tone as such; other exercises can be devised for that side of art study. To make tone studies of the figure with its background is to degrade it from its high purpose; but this does not imply that it should be drawn as existing by itself—isolated in space, for by the use of expressive line the tone of background can be suggested. The degree of emphasis of the edge treatment will show whether the background is darker or lighter than the general tone of the figure. This aspect is considered in detail in the remarks on Edge Study.