Home > Directory of Drawing Lessons > How to Improve Your Drawings > Drawing Lights and Shadows > The Wrong Way of Drawing Shadows

How to NOT Draw & Shadows Shadows and Lights with the Following Drawing, Lighting & Shading Lesson

|

|

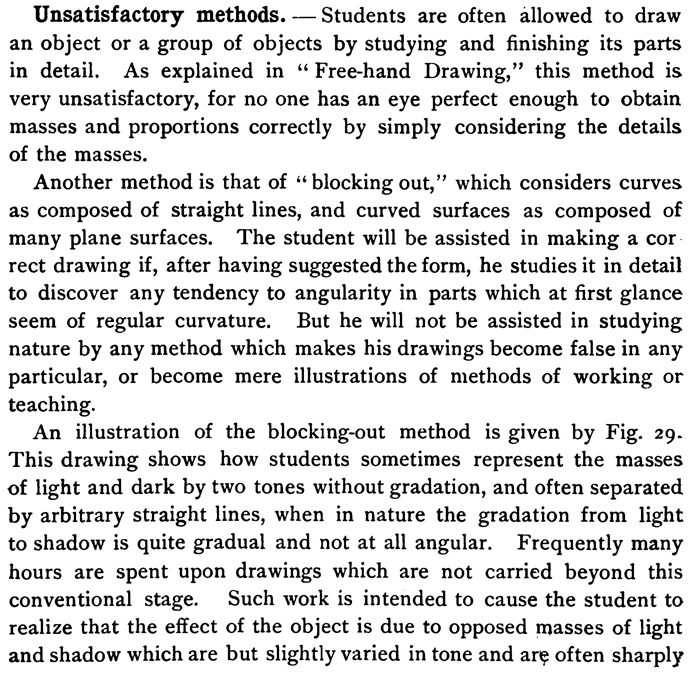

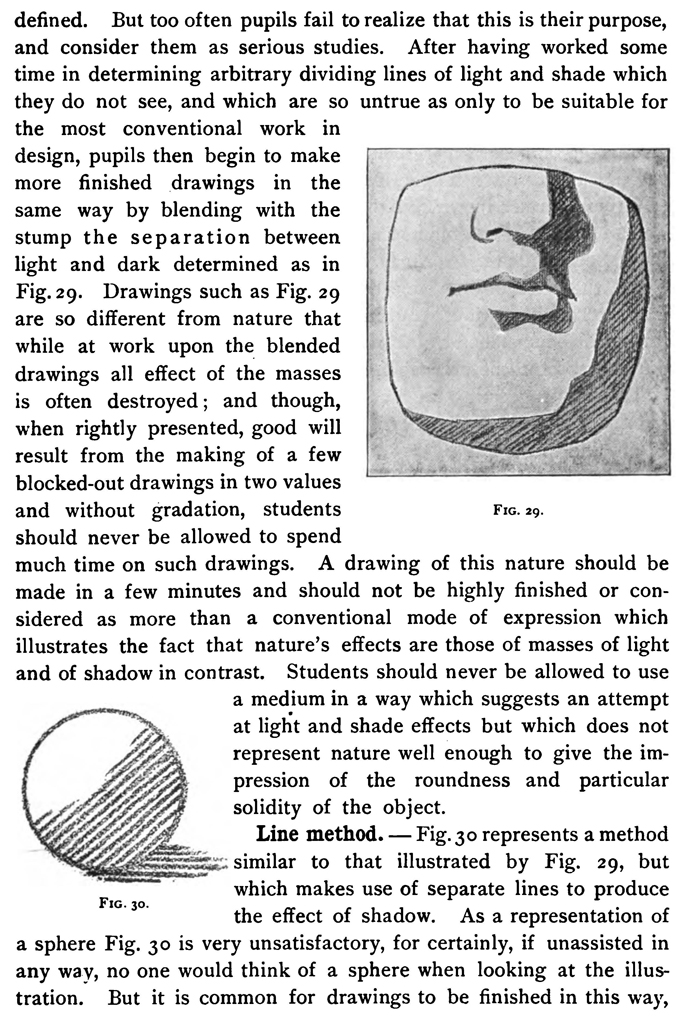

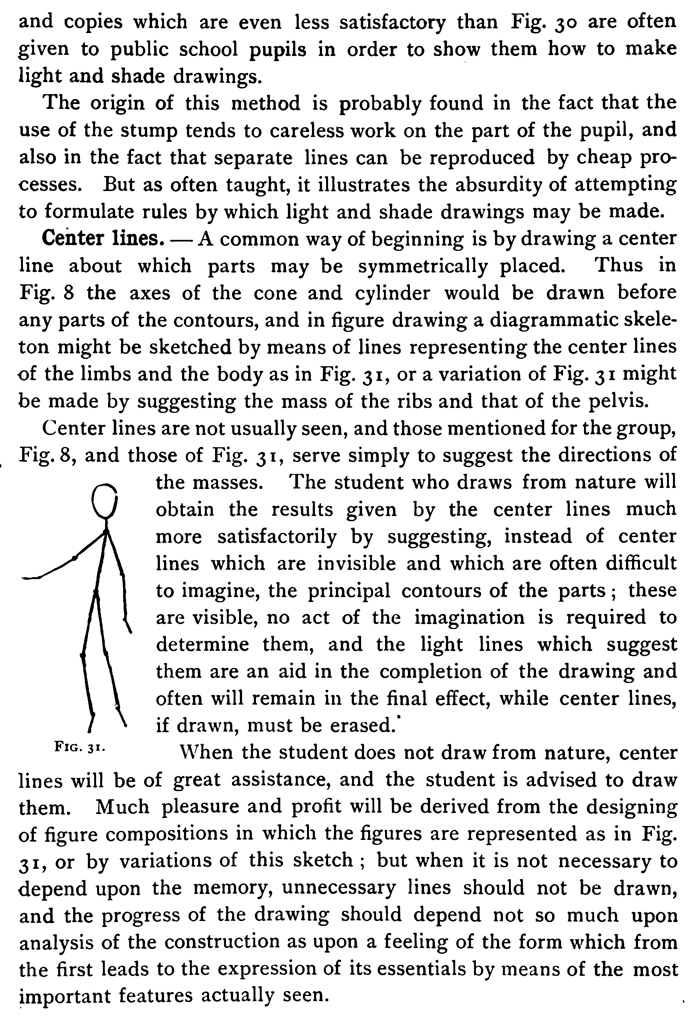

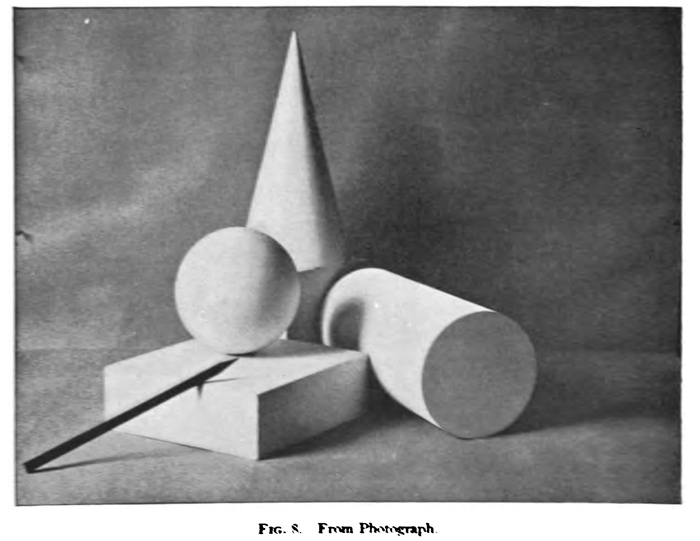

Unsatisfactory methods.Students are often allowed to draw an object or a group of objects by studying and finishing its parts in detail. As explained in " Free-hand Drawing," this method is very unsatisfactory, for no one has an eye perfect enough to obtain masses and proportions correctly by simply considering the details of the masses. Another method is that of " blocking out," which considers curves as composed of straight lines, and curved surfaces as composed of many plane surfaces. The student will be assisted in making a cor rect drawing if, after having suggested the form, he studies it in detail to discover any tendency to angularity in parts which at first glance seem of regular curvature. But he will not be assisted in studying nature by any method which makes his drawings become false in any particular, or become mere illustrations of methods of working or teaching. An illustration of the blocking-out method is given by Fig. 29. This drawing shows how students sometimes represent the masses of light and dark by two tones without gradation, and often separated by arbitrary straight lines, when in nature the gradation from light to shadow is quite gradual and not at all angular. Frequently many hours are spent upon drawings which are not carried beyond this conventional stage. Such work is intended to cause the student to realize that the effect of the object is due to opposed masses of light and shadow which are but slightly varied in tone and arc often sharply defined. But too often pupils fail to realize that this is their purpose, and consider them as serious studies. After having worked some time in determining arbitrary dividing lines of light and shade which they do not see, and which are so untrue as only to be suitable for the most conventional work in design, pupils then begin to make more finished drawings in the same way by blending with the stump the separation between light and dark determined as in Fig. 29. Drawings such as Fig. 29 are so different from nature that while at work upon the blended drawings all effect of the masses often destroyed ; and though, when rightly presented, good will result from the making of a few blocked-out drawings in two values and without gradation, students should never be allowed to spend much time on such drawings. A drawing of this nature should be made in a few minutes and should not be highly finished or considered as more than a conventional mode of expression which illustrates the fact that nature's effects are those of masses of light and of shadow in contrast. Students should never be allowed to use a medium in a way which suggests an attempt at light and shade effects but which does not represent nature well enough to give the impression of the roundness and particular solidity of the object. Line method.Fig. 30 represents a method similar to that illustrated by Fig. 29, but which makes use of separate lines to produce the effect of shadow. As a representation of a sphere Fig. 30 is very unsatisfactory, for certainly, if unassisted in any way, no one would think of a sphere when looking at the illustration. But it is common for drawings to be finished in this way, and copies which are even less satisfactory than Fig. 30 are often given to public school pupils in order to show them how to make light and shade drawings. The origin of this method is probably found in the fact that the use of the stump tends to careless work on the part of the pupil, and also in the fact that separate lines can be reproduced by cheap processes. But as often taught, it illustrates the absurdity of attempting to formulate rules by which light and shade drawings may be made. Center lines.A common way of beginning is by drawing a center line about which parts may be symmetrically placed. Thus in Fig. 8 the axes of the cone and cylinder would be drawn before any parts of the contours, and in figure drawing a diagrammatic skeleton might be sketched by means of lines representing the center lines of the limbs and the body as in Fig. 31, or a variation of Fig. 31 might be made by suggesting the mass of the ribs and that of the pelvis. Center lines are not usually seen, and those mentioned for the group, Fig. 8, and those of Fig. 31, serve simply to suggest the directions of the masses. The student who draws from nature will obtain the results given by the center lines much more satisfactorily by suggesting, instead of center lines which are invisible and which are often difficult to imagine, the principal contours of the parts ; these are visible, no act of the imagination is required to determine them, and the light lines which suggest them are an aid in the completion of the drawing and often will remain in the final effect, while center lines, if drawn, must be erased. When the student does not draw from nature, center lines will be of great assistance, and the student is advised to draw them. Much pleasure and profit will be derived from the designing of figure compositions in which the figures are represented as in Fig. 31, or by variations of this sketch ; but when it is not necessary to depend upon the memory, unnecessary lines should not be drawn, and the progress of the drawing should depend not so much upon analysis of the construction as upon a feeling of the form which from the first leads to the expression of its essentials by means of the most important features actually seen. Authority for all methods.It is possible to find noted authorities for almost any view of any question, and in art the words or work of men who are or have been prominent are used in support of methods opposed to those of this book. The study of values, for instance, has been neglected in many of the schools of this country and Europe, and is given little attention even now in some quite noted ones. In some schools pupils are allowed to finish one part of a drawing before other parts are even suggested. Thus in a figure we find them painting the first day the head, the second the shoulders, and so on till on the last day of the pose they get to the feet or possibly not so far as this, the background being carried along with the figure. By such work it is almost impossible to obtain a harmonious whole, for the effect which any part will produce cannot be determined until it can be compared with all the other parts, and until the whole canvas is covered so as to give the desired effect. This principle applies as much to an outline or a light and shade drawing as to a color study. But even if the eye were trained to work correctly under such difficult conditions, it would be impossible to obtain harmony by correctly drawing what is before the eye at different times, for the light and shade and color effects of the subject are continually changing. Even in the studio the effects due to sunshine and a gray day are entirely different. Not only this, but during different hours of the same day the effects of color and light and shade are different, and it will be impossible to produce a satisfactory whole by simply representing what is seen when the pupil works upon and finishes the different parts. Effect must be chosen.The sentiment of the drawing and its effects of light and shade and color must be selected by the artist from the different changeable effects which the subject presents, and then he must work all the time with these desired effects in mind. To do this he must suggest as quickly as possible the desired effect when it is before him, and in all later work he must be careful not to lose or injure it. It is most important that both the student and the artist work for the spirit and the effect of the whole until it is correctly suggested; then the detail may be studied and the parts finished. Public ideals often false.Not only in values but in outline work is authority to be found for inartistic methods. Thus we are told that a drawing should be finished bit by bit with firm, decided, and exact fine lines, or perhaps with soft gray lines drawn at one touch. It is not strange the public has come to regard the perfect circle drawn at first touch by Giotto as the symbol of the best art work, and to believe that perfection at first touch is not only desirable, but possible to obtain. We are told that there must be no variety of line in an outline drawing, and that in light and shade an exact and perfect outline should be secured, and then the light and shade placed within it. If instead of following the advice of any one author, artist, or teacher, each person should study for himself all the points involved, the adoption of inartistic methods would be far less general. Those who study for themselves will be led to ask why begin in light and shade work with an outline which often represents contours that are lost in the shadow, and which can no more express roundness than the circle suggests the light and shade upon the sphere.

|

Privacy Policy ...... Contact Us