Home > Directory of Drawing Lessons > How to Improve Your Drawings > Drawing Lights and Shadows > First Work in Drawing Lights and Shades

How to Learn How to Draw & Shade Objects and Figures with Important Lessons in Shading and Drawing Techniques

|

|

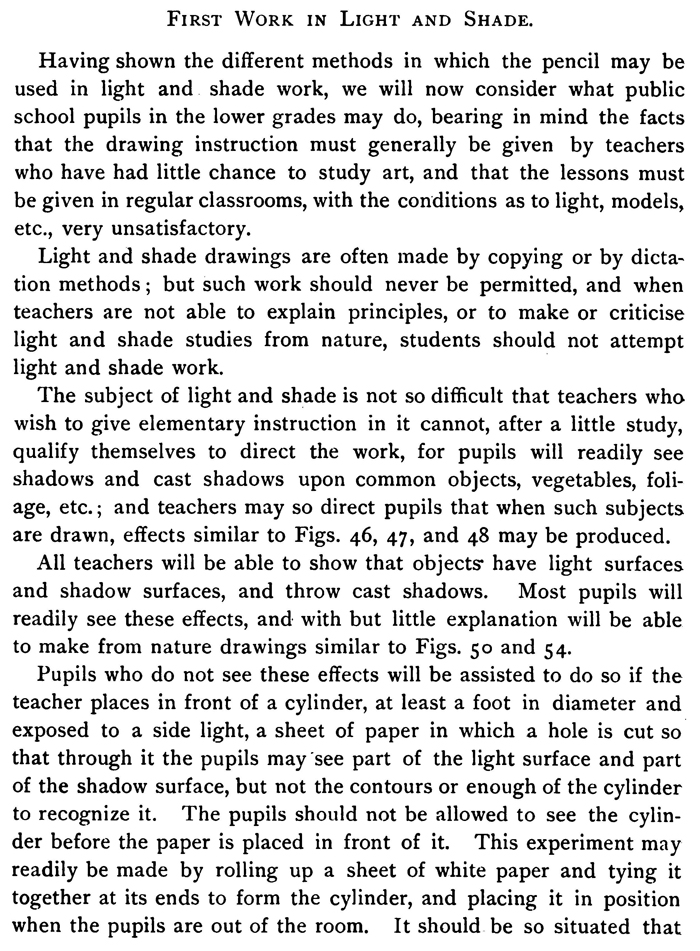

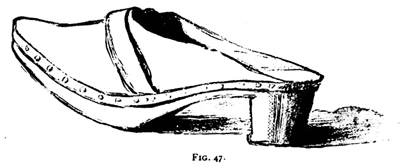

FIRST WORK IN LIGHT AND SHADE.Having shown the different methods in which the pencil may be used in light and shade work, we will now consider what public school pupils in the lower grades may do, bearing in mind the facts that the drawing instruction must generally be given by teachers who have had little chance to study art, and that the lessons must be given in regular classrooms, with the conditions as to light, models, etc., very unsatisfactory. Light and shade drawings are often made by copying or by dictation methods ; but such work should never be permitted, and when teachers are not able to explain principles, or to make or criticise light and shade studies from nature, students should not attempt light and shade work. The subject of light and shade is not so difficult that teachers who wish to give elementary instruction in it cannot, after a little study, qualify themselves to direct the work, for pupils will readily see shadows and cast shadows upon common objects, vegetables, foliage, etc.; and teachers may so direct pupils that when such subjects are drawn, effects similar to Figs. 46, 47, and 48 may be produced.

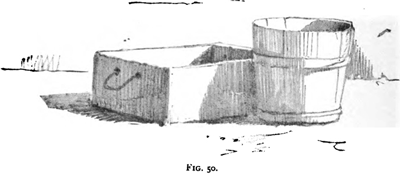

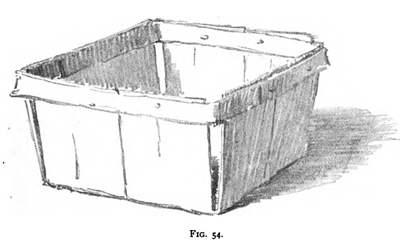

All teachers will be able to show that objects have light surfaces and shadow surfaces, and throw cast shadows. Most pupils will readily see these effects, and with but little explanation will be able to make from nature drawings similar to Figs. 50 and 54

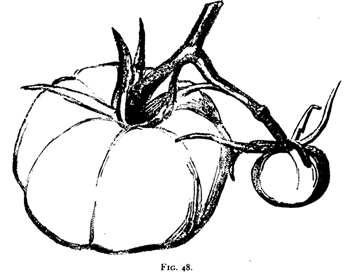

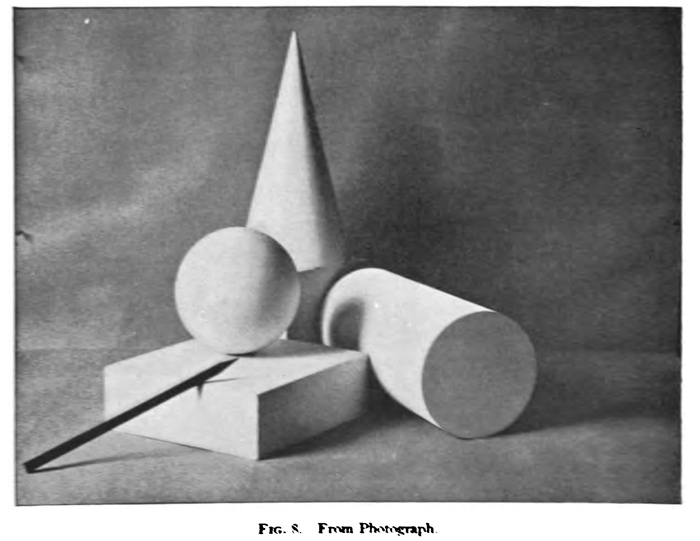

Pupils who do not see these effects will be assisted to do so if the teacher places in front of a cylinder, at least a foot in diameter and exposed to a side light, a sheet of paper in which a hole is cut so that through it the pupils may-see part of the light surface and part of the shadow surface, but not the contours or enough of the cylinder to recognize it. The pupils should not be allowed to see the cylinder before the paper is placed in front of it. This experiment may readily be made by rolling up a sheet of white paper and tying it together at its ends to form the cylinder, and placing it in position when the pupils are out of the room. It should be so situated that the pupils can see it only through the hole cut in the paper placed in front of it. There are few pupils who will not see the light and dark upon the cylinder when it is thus situated, and after they have done this, the paper in front of the cylinder may be removed, and they will then realize that the light and dark was really upon one white object, and due wholly to light and shade. Pupils who can see these effects of light and shade will readily represent them by simple masses, and may thus begin their study of nature's lights and shadows. When work more advanced than this is desired, it will be well to study the cube, or a similar object, as follows :First place the cube in a side light producing an effect similar to that of the plinth in Fig. 8, and have the pupils represent the effect as in Fig. 49.

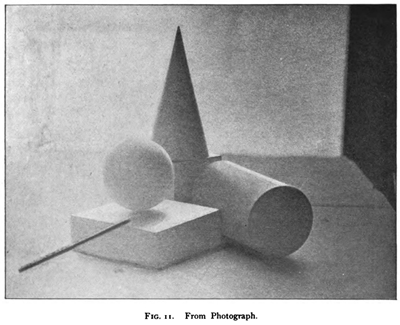

Next place the cube with the light in front of the pupils so that the effect is similar to that of the plinth in Fig. 11.

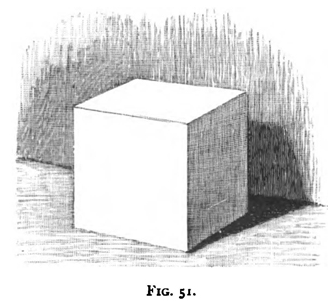

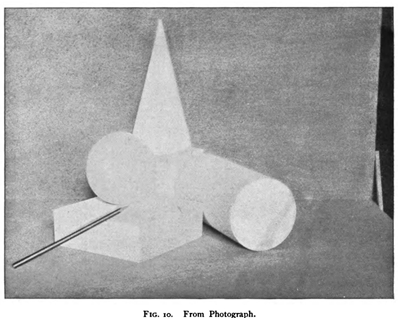

The pupils will represent the cast shadow and the two vertical shadow surfaces by dark tones, and the top of the cube by an outline. Next place the cube so that the light comes from behind the pupils, and so that the effect is similar to that of the plinth in Fig. 10, and ask the pupils to make a light and shade drawing of the cube.

The pupils have been accustomed to represent the cast shadow and the shadow surfaces by dark tones which have produced the effect of the drawings. But now the effect of the subject is entirely light, and cannot be represented by shading any surface of the object as the pupils have been in the habit of doing. This effect will show the pupils that it is often necessary to use a background, and this may now be represented so that the cube comes out light against it as the object does against its background in nature. The cube should now be placed in different positions and with different backgrounds, so that its shadow surface appears first darker and then lighter than the background, and the pupils should be asked to represent the value of the background as well as that of the shadow and cast shadow. Drawings such as Fig. 51 will result.

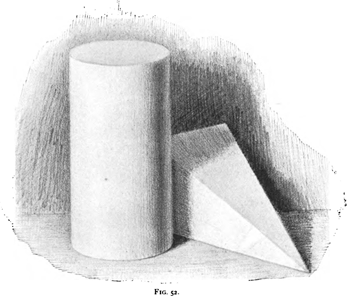

It is now time to ask the pupils to observe that the light faces are not equally light, and the sphere should be studied to show the gradation that there is in the masses both of light and of shadow. The pupils should make a careful study of the sphere from the object, and should give all the gradations that can be seen. After this they may study a colored object and a white object at the same time. In their work from this time on they should represent a background or not, according to the nature of the subject. They should understand that a dark object seen against a light background, or any object which appears darker than its background, may be effectively rendered without a background ; but when any object appears lighter than its background, in whole or in part, a sketch true in values cannot be made without the use of a background. If pupils are taught to observe nature, and understand that their sketches should be truthful representations of what they see, they will be interested in the work, and will make rapid progress. The artistic method of making these pencil sketches is to suggest the proportions of the drawing and its principal masses by lightly indicating the principal shadows and cast shadows, and then strengthening them so as to obtain drawing and values at the same time. Public school pupils will not be able, however, to draw well enough to work in this way at first, and they will be obliged to indicate the outlines of the objects before beginning the shading. If in obtaining correct form the outlines become strong, the eraser should be used to make them very faint before the drawing is shaded. When possible no shadow or edge should be defined in a finished drawing by an outline ; and whenever a background is used the forms may always be shown by the values alone. Perfectly accurate geometric solids are not the best subjects for this work, as it is difficult to represent the facts of their form in a drawing artistically handled, and a subject such as Fig. 54 (above) is far I preferable to the cube of Fig. 49 (above) The type solids should, however, be studied first, and sketches similar to Fig. 52 are advisable, as they show at the same time the student's capacity for drawing truly and for rendering light and shade effects. At first pupils should be allowed to work slowly and carefully in order that the shading may not extend beyond the outlines ; and no directions should be given restricting them to shading by means of lines or by means of strokes in any special direction. They should use a soft pencil, having a wide point, so as to produce even tones in any way that occurs to them, and should at first think only of the values and the forms of these tones.

After the students have worked for some time representing the darks by tones secured by whatever use of the pencil is natural to them, they will work more freely and directly, and they may then be asked to produce shading by moving the pencil back and forth in the direction of the surface to be shaded, so as to obtain the shading by means of lines whose direction helps to express the surface. Thus on the foreground the strokes of the pencil may be about horizontal, and upon the background they may be vertical or inclined a little from the vertical. The pencil strokes that form the shading upon any object may have such a direction that they help to express the form of the object ; but it will not be possible to formulate rules for determining the direction of the pencil lines used in shading, for there must always be variety, and the principal directions must be contrasted by lines having other directions. It will not do for the lines of shading always to be vertical upon vertical surfaces, or horizontal upon horizontll surfaces, or oblique upon oblique surfaces, or to follow the exact curvature of curved surfaces ; but the pupil will be assisted by remembering that such directions will often produce the most satisfactory results. The effect will be most satisfactory when the shading follows these general directions, and is varied by other lines which keep the effect from becoming monotonous. Pupils in the lower grades do not draw freely enough to profit by devoting much attention to the direction and kind of lines by which the shading is obtained. Until pupils can draw quite freely and give the masses of light and shade readily, it will only be necessary to see that they use the side of a soft pencil so as to produce even tones of shade ; and also to see that they do not use its point, or a sharp or hard pencil, so as to produce fine lines either when shading or when drawing the contour of any object. The help to be derived from the most suitable direction of the pencil lines, or rather tints by which the shading is given, is mentioned in order that teachers may understand that rules for handling cannot be given, and that the only point which should decide satisfactory technique is whether it gives a pleasing and true impression of the object represented. To be satisfactory, pencil work must be free and must be varied,—just how is a question which can only be decided by each pupil through his own efforts; and the individuality of each will express itself, so that among sketches by half a dozen different persons there may be no two sketches which are alike in handling. Study from nature and the comparison of his work with that of artists will enable the student to gain an interesting technique with the pencil or with any other medium. It will be possible to study very simple light and shade effects in a common schoolroom, the object being placed near the window. But to make at all finished studies it will be necessary to have a good light. When rooms are situated so that groups cannot be arranged to receive light from one window, it will be necessary to make special arrangements. A group may be arranged upon a drawing board placed upon a stool in front of a window. If sunlight enters the window it should be curtained by white cloth. A board may be placed behind the group to serve as a background. If light comes from the opposite side of the room, it should be shut off by placing a second drawing board vertically at the side of the group. To obtain in such ways the proper conditions requires much time and preparation ; but this is necessary if the subject is to be attempted when suitable rooms are not provided. Pupils who have used the pencil for light and shade work may use the brush for this purpose. In the upper grades pupils who can give light and shade effects with the brush may sometimes be able to study from still life with water colors. Such pupils may also use pen and ink, but this medium should not be used when pupils are not able to make good light and shade drawings with the pencil. No work in drawing should be allowed in the drawing hour of such a nature that pupils cannot by study discover their errors, or of such a nature that the teacher cannot criticise the drawing. Progress is not made by attempting difficult subjects or the technique of the artist. Progress comes only from work upon drawings whose errors the pupils can largely discover themselves, and which beyond this point can be criticised by the teacher. As in all teaching, the great trouble in public school work has been, and is, that students wish to study subjects too difficult for them; they wish to make light and shade drawings and to paint before they can draw in outline ; they wish to draw the human figure before they can draw a cube. Often teachers allow pupils to spend their time in attempting the advanced when they cannot represent the simple subjects. Thus, in the public schools, pupils often make illustrative drawings from imagination, depicting subjects that would require the skill of a trained illustrator to draw with any degree of truth. Such work interests the pupils and trains the intellect, and is valuable in this way, but it cannot train the eye to see. It is not properly the study of drawing, and should not be permitted to take the place of that study of nature and that criticism of all drawings which discovers their errors, for advance is impossible except by discovery of error. The teaching which is based upon the idea that criticism of drawings will discourage the pupil, and that if allowed to work without criticism he will in time outgrow his errors and draw correctly, will result in the loss of much valuable time and effort. Art students who realize the difficulty of success as artists will do well to consider the problem of teaching drawing in the public schools, for by giving part of their time to this teaching they can support themselves, so that they can paint from love of art. To teach drawing well is not a low aim, and if advanced art students should fit themselves for teaching by normal study, they would often benefit themselves while elevating drawing instruction. School committees would assist in improving drawing instruction if in selecting teachers of drawing they acted on the principle that the best teacher is, other things being equal, the one who can draw and paint the best. It should be understood that the art teacher can never become perfect in his profession, but must always be studying and growing in artistic power. If the best results are desired, the director or special teacher of drawing should have at least two days each week in which to study, to draw, or to paint. Drawing teachers are often expected and feel compelled to prepare papers and materials for teachers and classes, so that all their time out of school is occupied in work which amounts to the making of text-books and copies for teachers and pupils. There is no more reason why the drawing teacher should be expected to make such copies than there is why the music teacher should be expected to prepare music charts. Drawing teachers should not be obliged to do such work. The work they do in school is far more trying and difficult than any other teaching, and instead of working all the time, in school and out, they should do justice to themselves and their pupils by studying nature part of the time. In no other way can this most difficult subject of instruction be properly presented. Committees should also understand that no system of drawing instruction can be devised which will dispense with the special teacher, or which can succeed without a competent specialist to instruct and direct the regular teachers. |

Privacy Policy ...... Contact Us