Home > Directory of Drawing Lessons > How to Improve Your Drawings > Drawing Lights and Shadows > Drawing Object Under Various Lights

Techniques for Shading Shadows and Lights with the Following Drawing Methods Lesson

|

|

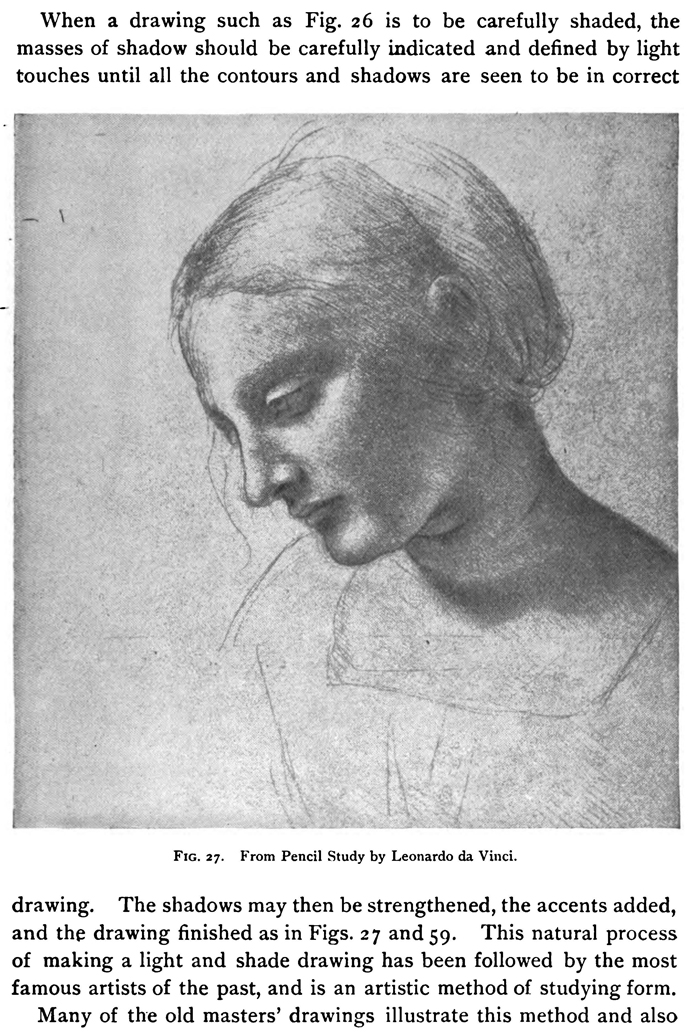

TECHNIQUE AND METHODS.Depends on individuality.Little would be said upon this subject here if it were not for the fact that so much attention is often given to it that it is necessary to show that matters of technique are not of first importance. Technique or handling means the way in which any medium is used to produce an effect, and to the artist it is of great interest and importance, for upon the way in which the medium is handled depends the effect of the sketch and the time required to produce it. Handling is the result of temperament and education, and is very different with different people. The same subject may be represented by half a dozen different artists, and the handling of no two sketches be alike. The time spent upon them may range from a few hours to many days, and to the public the results may not be very different in effect, or, on the other hand, they may be so different that they would hardly be accepted as painted from the same subject. Depends on education.The average person rarely changes the habits and ideas which are his by birth and education. Almost every one has perfect faith in the theories which he holds, and often will not admit that the theories of others are worth consideration. On the contrary, he tries to convert those who differ from him, and sometimes he refuses to consider an opinion for which no authority is found in the school to which he belongs. If his mind questions the correctness of any point decided by his authorities, he is often too timid to let his doubt be known, and he thus sees and thinks through others. We often recognize in the work of an artist the technique of the teacher with whom he has studied, and, if we know him, find that he sees no merit outside the work of his own school. The ability to be independent is possessed by the few who lead. Naturally the major ity seek some one to follow, or, rather, follow instinctively the leaders with whose temperaments they are in harmony. In art this causes the different schools, and gives rise to the conflicting ideas concerning art education. Art judged by unimportant details.The public generally is pleased by detail, the more detail the better, and it compares all work with that of a Meissonier or with a photograph. Some who have studied have passed beyond the stage of search for detail, but even to many of them art often consists principally of the technique of the picture, which is good if similar to that of the artists whose work they have chosen as ideals. Art instruction influenced by fads.The instruction in schools, both elementary and advanced, is too largely influenced by the latest technical fad, which is the technique of those who influence art matters at any particular time. So method supersedes method — there is no accepted standard, and art instruction often deals with matters relating to a medium and its handling, while the foundation of drawing and values receives far too little attention. This is especially true of the work in the public schools, where it has often been necessary to have instruction in drawing given by teachers who have had little opportunity to study drawing. Consequently students have sometimes been told that all methods except one are out of date and harmful, and that drawings made in other ways are bad. For instance, it has been claimed that a charcoal or other light and shade drawing must be made wholly with the point of the charcoal or other pencil and consist of separate lines, and that a drawing in which the lines are at all blended to form a tint is not good. The results of such teaching are generally most mechanical drawings, although they are often better than some of the copies provided to show public school pupils how to make light and shade drawings. Less important than truth.Technique bears the same relation to drawing that style does to the study of the elements of language. Therefore the teacher of elementary work should not allow his pupils to consider technique at all. The pupil should think simply of the truth of the drawing, and the teacher of the way in which the pupil may obtain the truth most quickly and easily. The teacher should remember that every medium may be used in many different ways, and should not restrict individuality of expression that produces true drawings. The aim of a drawing is to create an impression of nature, and any drawing must be bad which, instead of doing this, causes one to think at once of paper and crayon or whatever other medium may be used, or of the way in which it is used. This is a good test for poor technique. With any medium certain facts are self-evident, as, for instance, that the surface of the paper must not be destroyed by erasing ; but such essential points will be discovered by any one who studies, and what is meant is that the spirit of the drawing should always be thought of first, and that difficult methods should not be studied because they are interesting to some noted person. Concerns the advanced student.The art student must be interested in technique, for it involves the mechanical points which he must master thoroughly before he can express himself freely; but questions of technique concern principally advanced students. The elementary student should be taught that the medium must not force itself or its handling upon the eye ; that there must be in any drawing a harmony of treatment throughout its parts ; that it will not do to finish one part perfectly and smoothly and have parts equally important imperfectly and roughly finished. The ability and training of the student, and his aim in studying, must decide whether any medium or particular way of using it should be chosen ; but the elementary teacher must consider simply how he can most quickly train his pupils to see and draw correctly, and he will discard any method which makes the pupil think of the point and the kind of line he is drawing instead of the form or value that should be represented. Many ways of using every medium.The pictures and drawings of the best artists should be studied, for the student will be greatly helped and inspired by them. Great variety of handling will be found in them and also in those by any one artist, and study of the technique of others will soon convince one that there are many ways in which any medium may be used with the best results, if one with artistic feeling can draw well. Less important than beauty.The public should be taught that the technique of a picture concerns them little, and that if a picture is beautiful in form, color, and sentiment, it should be admired for these qualities, and not because it is smoothly painted or roughly painted, or because it gives evidence of rapid work or of the greatest labor; for art does not consist in technique, but in results which come from and appeal to the soul, and are embodied in mind and not in medium or its handling. If this could be understood and the public would look beyond the surface of the canvas, a great advance would be made. METHODS.Harmony of methods.In "Free-Hand Drawing" it is shown that the pupil who studies outline drawing should first suggest his impression of the mass of the group and of its important lines; that he should begin with its essentials and from the first express character by light touches suggesting the most important features ; and that he should change these touches without erasing until finally the form is correctly represented. There should be from first to last a harmony in the methods employed by the pupil, whatever the mediums used, and if the above is the best method for studying outline drawing, it must be the best for the study of light and shade. In practice the student who has thus studied outline will continue these methods, and the transition from outline to light and shade will naturally follow the making of outline drawings, for the touches required to obtain the correct form will often blend together and suggest the light and shade effects of the object. Outline study leads to that of values.To make a shaded drawing giving simply the relative values of a cast or a figure without the use of a background is a natural continuation of the process by which the outline should be obtained ; for the trial lines follow the surface they represent and give the effect of shade as it is rendered by the pencil of the artist. The artist feels the surface he represents and expresses its form and gradations of shade by strokes which, following the surface, help to give the roundness and character of the part whose contour and value they represent. When a drawing such as Fig. 26 is to be carefully shaded, the masses of shadow should be carefully indicated and defined by light touches until all the contours and shadows are seen to be in correct drawing. The shadows may then be strengthened, the accents added, and the drawing finished as in Figs. 27 and 59. This natural process of making a light and shade drawing has been followed by the most famous artists of the past, and is an artistic method of studying form. Many of the old masters' drawings illustrate this method and also the fact that drawings with light and shade effects may be very conventional and far from representing truly all the values of the subject. They are drawings rather than paintings ; that is, they are studies of form more than of values, and do not give either the relative values of the object alone or its values in comparison with its surroundings. The word " painting," as here used, means a drawing in which values and the effect are made of first importance ; and in this sense a painting may be done in charcoal or the pencil as well as with the brush. Use of background. A drawing begun in this way may be carried as far as is desired; it may give all the values of the object alone, it may suggest a background, or it may give the full values of the object and its background. To study values.The best method of studying when values are first in importance must now be considered. In this case it is most necessary to obtain the effect of the masses, and the student should begin by suggesting them. As quickly as possible the entire surface of the paper should be covered so as to lightly express the principal lights and darks. When the masses of dark have been suggested, the student should study form and construction until the masses are seen to be correctly indicated; then they should be strengthened, their details brought out, and the study finished by carefully representing all details just as in the case of the drawing (Fig. 27) which is a study of form and local values instead of a study of full values. But the student must not forget the impression of light and dark which the subject creates, and while perfecting the drawing, the greatest pains must be taken not to lose the values. Drawing and painting.In reality the student should be working in one of two directions without regard to the medium with which he makes the light and shade drawing. He should be studying drawing or studying painting, — using the word " painting " in the sense that a representation of all the values causes one to think of the subject simply and not of the medium employed, and in the sense that a drawing or picture is a work of art in proportion as it hides the medium employed and its handling. To obtain the best results the art student must both draw and paint, and, even while working with black and white, he must use both methods. Frequently art students study drawing alone, and this accounts for the general disregard of values. Representing a cast or a figure with crayon or pencil upon white paper without the use of a background is study of drawing, and certainly cannot give the effect of the object, when the object is light against dark instead of dark against light. It is not surprising that pupils whose work has been largely of this nature should not be able to see the values in a simple group of still life. The difference between a sketch and a study, and that between a study or drawing, and a painting (using painting in the sense of a drawing giving values), is shown by Figs. 26, 27, and 28. Fig. 26 is by Raphael, and represents the Virgin and child. It shows the first light touches and the stronger ones by which the form was gradually obtained, and illustrates the fact that the artist works upon figure subjects just as the student was directed in "Free-Hand Drawing" to begin his study of the geometric solids. Fig. 27 is from a pencil study by Leonardo da Vinci ; it is a careful and true drawing as far as character and modelling are concerned, but it does not give the values, and is not a painting in the sense of representing light and color in addition to the form. Fig. 28 is from a charcoal study by Sir Joshua Reynolds, and when compared with Fig. 27 illustrates the difference between a study of form simply, or a drawing, and a study of values which may be called a painting. Although done with charcoal, this drawing gives at first glance the effect of nature as regards light, color, and form, which it should be the aim of the painter to represent ; and it is much more satisfactory as a painting than many colored paintings which are not true in values. When the student is at work he should always have in mind the making of a sketch such as Fig. 26, or a study such as Fig. 27, or a painting such as Fig. 28, but he must not forget while working for tone and values that Fig. 28 is as careful and as true in drawing as Fig. 27. Painting method advisable.The public school pupil should begin with pencil outline ; from this he should advance to light and shade work with the pencil, which may at first represent objects without a background ; but in the high school he should study values, and although pupils study drawing without intending to make a specialty of art, they should be taught to look at nature artistically so as to realize the effects of light and dark and color which she presents. To do this pupils must study values, and nearly all light and shade study in high and all elementary schools should represent the object and its surroundings in their true relations of light and dark. Time-sketches.Students so frequently forget the subject they are studying, while thinking of the medium or of unimportant details, that time-sketches are necessary if rapid progress is to be made ; and, regardless of the medium used, students of light and shade should be obliged frequently to make time-sketches in so short a time that they are compelled to work in the right way. If the time of the first sketches is limited to a few minutes each, pupils are obliged to look for the essentials, and to suggest them by light touches. If they mechanically try to produce finished results representing details their drawings are too incomplete and poor to satisfy themselves. Students who work mechanically and study details will, on comparing their work with the drawings of students who have worked properly, generally try to see effects, and to suggest them lightly and quickly. The first time-sketches in light and shade may do little more than suggest the principal masses of light and dark. Students should understand, while. making them, that their aim must be to represent what is seen as far as this is possible in the time, and to do this by telling the truth always, and never allowing any part of the drawing to be different in effect from the part it represents. Students often work carelessly, knowing that parts of the drawing are different from the parts they represent, but intending to change them later on. Such work produces drawings which are dark when they should be light, and which are very unsatisfactory and different from what the students know they ought to be. A student should not begin to make a drawing until he has studied the subject and determined just what he has to do, in order to place no darks upon the drawing except to suggest corresponding darks of the object, and in order to avoid representing unimportant details either of light or of dark before the masses are correctly expressed. The spirit and the effect are the important things, and these should be thought of first and last ; if this is not done the drawing must always be mechanical. The artistic method is that which at first lightly suggests the important features, and then, as they are found to be correct, strengthens them and accents the drawing, never allowing it to remain false in effect or values, so that whenever the student stops work the drawing is satisfactory and true as far as it has been carried. |

Privacy Policy ...... Contact Us