Home > Directory of Drawing Lessons > How to Improve Your Drawings > Adding Tones and Values > Learn to Draw Values

Drawing Lights, Darks, Mid-Tones and Color on 3-Dimensional Shapes and Objects by Learning How to See Values and Tones with the Following Drawing Lesson

|

|

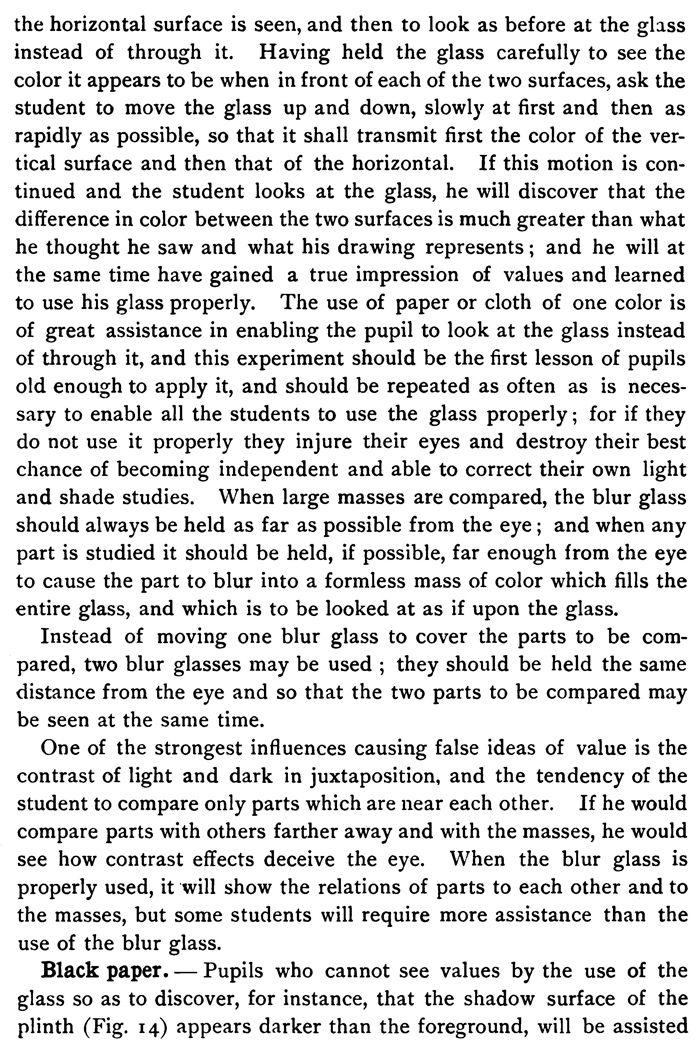

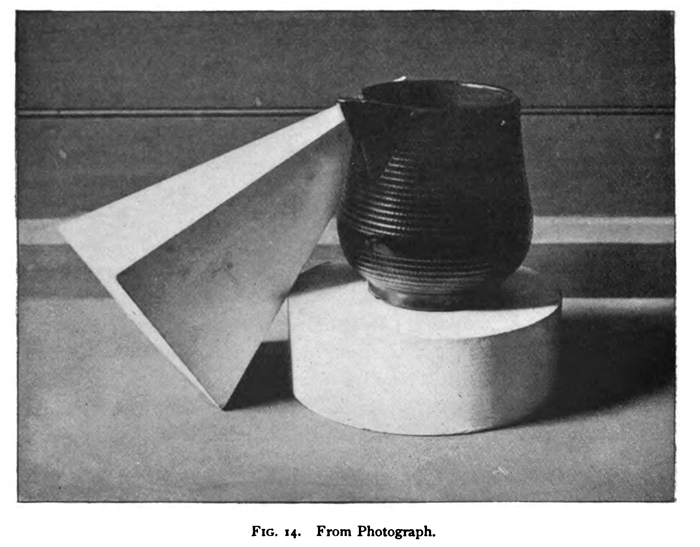

TESTS FOR VALUES.Perfect sight not common.The first and most difficult problem for the art student is to learn to see, for only a few ever learn to see perfectly; and those not giving the matter special attention seldom see the actual appearance of either form, light and shade or color. To realize perfectly what the eye pictures for the mind to read concerning simply the apparent forms of objects requires many years of serious study, and is so difficult that even after this study the artist of reputation is very apt to be deceived and draw what is very different from the image of the eye. In " Free-Hand Drawing" it was shown that a course in free-hand perspective assists the student to avoid faulty representations of the geometric forms, which are most likely to deceive even the practiced eye of the artist. Any student who draws the geometric forms, and tests them as explained in "Free-Hand Drawing," will soon realize that it is difficult to see correctly; for he finds what he thinks he sees to be very different from what the tests prove that he does see, and it is easy for him to convince himself that he cannot see correctly. Values more difficult than drawing.To convince an art student that he cannot see light and shade or color correctly is far more difficult than to prove that he cannot see form correctly. To draw correctly requires, first, an eye naturally true, and, second, a serious and extended course of study; but almost every serious student can in time teach himself to represent form correctly. The same student may work many months, even with the assistance of a teacher, and fail to see values or color correctly. To give the actual facts pictured in the eye concerning light, dark, and color is so difficult that few succeed; and even after years of study many see in nature only the actual facts known, or what they have become accustomed to think they see concerning the local colors of objects. Values not taught.If artists and teachers generally made the study of values as important as that of form, doubtless many students who do not understand what value means would become able to see values correctly; but the number would be small compared with that of those who are able to draw correctly, for serious students of the best teachers often work for many months before they realize how incorrectly they see values. The teacher who insists upon correct values requires much patience and ingenuity, for his pupils cannot readily help- themselves, nor can they believe the teacher who tells them, for instance, that they ought to see, in some special group, dark blue lighter than yellow, when they know that they see it as they think it ought to appear, — darker than the yellow. In such cases the teacher must either be content to say : "If you cannot see it, you must draw it as I say, and in time you will see it as I do," or he must prove to them that at first their eyes tell them nothing but the most glaring falsehoods about all that they see. When pupils realize this fact, and have once received a genuine sight impression concerning values, they will ever afterward see things in a new way, and their improvement will be rapid. Eye sees details instead of values.To see values and realize the effect of the masses, the eye must be used for this purpose only. This is a difficult problem for the student, for naturally the eye is focused upon a single detail, which is clearly seen. The vision passes rapidly over the whole of the group, taking in all its details by means of this careful study, which is of just the same nature as that which the scientist bestows through his microscope upon the specimens he studies. The only difference in their methods is that the motion of the eye of the art student is very rapid, and that the lens of the eye takes the place of the microscope. The scientist sees details, and very properly, since these are what he is to describe. The art student also sees details, and too often his work indicates that he must have examined each little bit as if through a microscope. In his first drawings he usually so magnifies the importance of every detail that his drawing is unintelligible, and gives not the faintest suggestion of the impression produced upon the eye which sees the effects of light, dark, and color in their true relations. The art student must learn that the artist and scientist work for entirely different ends, — that the aim of the artist is not detail, but the spirit and character of the whole, and that this cannot be obtained without making it of first importance and thinking first of the long lines, the large masses, and the effect of the whole subject. Blurred vision necessary.The effect of any subject is never realized when the student looks at any one part ; he must look at the group all at once. The whole of any subject can be seen at once only by seeing all its parts equally and thus indistinctly. That is, the eye must focus on no one part, but be in focus for an object in front of or behind the group ; then all its parts may be seen indistinctly at one time. The student will realize what is meant by blurred vision by closing the eyes gradually until the group can barely be seen between the lids and the lashes ; this cuts off most of the light and obstructs the sight so that the objects are blurred. Blurred vision may also be obtained by holding a pencil in the hand and in front of the group and looking at the pencil, which will be seen sharply, while the group will be seen very indistinctly. To see the whole at once is difficult for the art student, but the artist finds it easier than the searching gaze which the art student employs, because the artist sees effects unconsciously with blurred vision, which does not tire the eyes. Many aids to the correct seeing of values have been used ; among them the following are those of most assistance to the student. Claude Lorrain mirror.This is a mirror which gives a reduced image of the object, and has a black reflecting surface which diminishes the light so that the relative values may be studied more readily than in the group. A substitute may be made by painting one side of an ordinary piece of plate glass with ivory black. Common mirror.This is often used by artists and is a valuable aid, as its image reverses the lines of the group and the drawing, and by showing the parts in new relations makes errors prominent to which the eye has become accustomed. When the drawing is placed beside the group, and the mirror as far as possible from the group, it enables comparisons to be made from a distance twice that which could otherwise be obtained. The student will obtain much assistance from this mirror. Diminishing glass. This is a lens concave on one or both sides, which produces a small clear image of the group. The image is so small that it may readily be seen at one glance, and thus the values of the different parts be more easily seen. But even here the tendency is for the students to study the details of the image instead of its effects, and thus lose the advantage to be derived from the glass. The blur glass.This is simply an ordinary magnifying glass of about 15 inches focus. It should not be less than 12 inches focus or more than i6 inches or i8 inches. A rough lens about 2 inches diameter can be obtained at an optician's for about fifteen cents, and may be framed by cutting a circular hole in a piece of cardboard so that it will receive the lens, and then cutting smaller holes in two more pieces, and gluing one to each side of the first piece. The glass is thus protected so that it will not break if dropped, and the cardboard is also an improvement because it hides from sight all except the parts seen through the glass. If this glass is held so that the group may be seen through it, the outlines will be blurred and all detail softened. In this way the masses of light and dark are rendered so prominent that the student sees them as perhaps he never would without the glass. It is said that the use of such a glass must be injurious, and consequently pupils should not be allowed to use it. Those who think thus do not understand that the glass is to be used not for seeing, but to prevent seeing, and should not be used to look through, but to look at. In other words, the eyes must be focused upon the glass held in the hand, and not upon the group behind the glass, for if the student looks through the glass at the group, he will strain his eyes and be almost as badly off as when without the blur glass, for his eyes will adjust to the glass so that he will still see too much detail. To teach the proper use of the glass, secure a sheet of gray paper or of cloth of one color upon the wall or any vertical surface so that its lower portion may rest upon a horizontal surface. Ask the student to make a light and shade drawing representing simply these two surfaces. This will cause him to decide as to the difference in value between the two. Having made the drawing, ask him to hold the blur glass up so as to see through it the vertical surface, and then, ask him to look not through the glass, but at it, to discover the color which it appears. Now ask him to hold the glass so that through it the horizontal surface is seen, and then to look as before at the glass instead of through it. Having held the glass carefully to see the color it appears to be when in front of each of the two surfaces, ask the student to move the glass up and down, slowly at first and then as rapidly as possible, so that it shall transmit first the color of the vertical surface and then that of the horizontal. If this motion is continued and the student looks at the glass, he will discover that the difference in color between the two surfaces is much greater than what he thought he saw and what his drawing represents ; and he will at the same time have gained a true impression of values and learned to use his glass properly. The use of paper or cloth of one color is of great assistance in enabling the pupil to look at the glass instead of through it, and this experiment should be the first lesson of pupils old enough to apply it, and should be repeated as often as is necessary to enable all the students to use the glass properly ; for if they do not use it properly they injure their eyes and destroy their best chance of becoming independent and able to correct their own light and shade studies. When large masses are compared, the blur glass should always be held as far as possible from the eye ; and when any part is studied it should be held, if possible, far enough from the eye to cause the part to blur into a formless mass of color which fills the entire glass, and which is to be looked at as if upon the glass. Instead of moving one blur glass to cover the parts to be compared, two blur glasses may be used ; they should be held the same distance from the eye and so that the two parts to be compared may be seen at the same time. Black paper.Pupils who cannot see values by the use of the glass so as to discover, for instance, that the shadow surface of the plinth (Fig. 14) appears darker than the foreground, will be assisted if the teacher holds in front of the group a sheet of black paper in which holes are cut so that through one the student sees simply a part of the shadow, while through the other he sees simply part of the foreground. When the two parts to be compared are seen without the influence of the surrounding parts, there are few students who will not see the values truly. The paper should be held near the group, and both sides should be a dead black in order that the back surface of the paper may not reflect light enough to the group to change its values. The difficulty is to enable the student to realize for the first time that the light object often appears darker than the dark object. A mug of a light yellow color and having a pewter cover is an excellent object to use to show this fact. If it is placed on its side so that the cover is toward the light, the cover will appear lighter than the shadow surface of the mug. Few young pupils will realize this fact, and those who do realize it will be astonished to see the great difference in value which is shown when the two parts are compared by the use of the black paper which the teacher holds near the mug. Pupils who fail to see the values by use of the blur glass will almost always see them when they see in this way simply isolated spots of each color, and teachers should use this test when students show that they do not use the glass properly. Black card.The pupils may apply this principle by using a piece of black cardboard through which small holes have been made at varying intervals. The card may be of any smooth piece of cardboard. The holes should be clean, round, and of varying sizes, and they should not press out the surface of the card ; if this happens, it should be pressed back or trimmed with a sharp knife until both sides are smooth and flat. Both surfaces should then be colored with india ink or any dead black color; and also the edges of the holes. If this card is held in front of the group, it will hide from the eye all except the small parts which may be seen through the pin holes, and the card may be held so that any two parts whose values are to be decided may be seen through different holes. This card is of great assistance to elementary pupils, and it should be used occasionally to verify their work. The size of the holes depends upon the distance of the group and the distance at which the card is held from the eye, and may vary from a pin hole to one or M. of an inch in diameter. This card will assist the student to obtain true values and also to obtain what is essential and difficult to secure, — a gray and luminous drawing. The tendency of the pupil is to pile on the charcoal and make a black, heavy drawing, and it is difficult for pupils to realize that effect and solidity are not due to black, but to contrasts of masses of grays ; when the student looks through the card which is shaded by the hand, he realizes that there are no blacks in his subject. The chief value of the black card lies in the fact that it enables each pupil to remove at will the deceptive effects due to the contrasts of different values. If he could or would use the blur glass properly, the card would not be necessary ; but it is so difficult for some to look at the glass instead of through it that the card is very helpful. Black frame.A piece of black leather or cardboard in which a rectangular opening is cut will help to impress this fact of the luminosity of nature's effects upon the student, and to make him realize that a true drawing cannot be one which is black or heavy. Light into shadow.The student will often be assisted to see the values of two parts, as, for instance, the cast shadow upon the white cast (Fig. 5), and that of the cast upon the panelling, if the teacher holds or places an object so that it shall throw the whole of the cast into shadow. The pupil will often make the cast shadow on the cast as dark as that on the wall, for the contrast of the shadow and light upon the cast makes the shadow appear much darker than it really is. If the light parts of the cast are thrown into shadow, the part originally shadow changes but little in value, for it receives no more, and generally but little less, light than at first ; and when the effect of contrast is removed, the student will see that the cast shadow on the cast is much lighter than that on the background. Study at a distance.The least mechanical and most satisfactory test, and the one which should be applied most frequently, is simply placing the drawing beside the group and comparing it with the group when the student is as far as possible from the group. When comparing them, the eyes should be out of focus, so that the drawing and the group may be seen equally at the same time, and the student should ask if the drawing gives the impression of the group and of nature, or if it gives the effect of a sheet of paper slightly tinted. Does it present the same masses of light and dark that the group does, and are the contrasts of these masses as strong as those of the group? Are the darks of the drawing as simple and dark as those of the group, or are they cut up by exaggerated reflected lights ? Are the lights of the drawing as broad and as light as those of the group, or are they cut up by exaggerated grays ? The student who will ask these questions when he sees both drawing and group equally, and of course indistinctly, can hardly fail to discover the most important errors of the drawing. It is very important that the drawing be thus seen from a distance repeatedly from its early stages, until its effect agrees with that of the group ; when this happens the student must complete the drawing by giving the essential detail. While drawing this he must be careful not to change the masses, and until the drawing is completed it must be viewed from a distance occasionally in order to make sure that the detail is not too prominent. Use of the hand.A convenient and simple way of obtaining the results given by the use of the black card is afforded by looking through a small opening which may be formed by compressing and bending the first finger upon the thumb. The hand may be moved so that one after another the parts to be compared may be seen through the finger, or both hands may be used and two parts compared at once by viewing one through one hand and the other through the other. Tipping the head.Another test, which is simple and very valuable, is that of tipping the head until the eyes are in a vertical line instead of in a horizontal one. Any one who will view the simplest landscape in this way will be surprised to see how much more color it seems to have than when seen naturally. The principal reason for this is that when the head is tipped the objects are seen in such unusual relations that their forms are not thought of, and all the attention is attracted to contrasts of light, shade, and color. The student of color will find that this test accomplishes the same result as the use of the blur glass, and it will be equally valuable in the study of light and shade. Tests inferior to feeling.At first every student will require some mechanical test or aid to enable him to see values correctly, but he must not depend upon these tests any more than in determining contours upon measurements of proportions ; for tests are of no more assistance in producing a work of art whose values are true than measurements are in producing correct drawing. Good art can never be produced mechanically, and the artist must depend upon his eyes and his feeling for both good drawing and good values. But the student will obtain his education in the direction of values just as he will in that of form, and if he does not adopt some means of discovering the errors of his first studies, he will repeat them and possibly never discover them. Tests lead to feeling.The student is advised to apply all tests with great patience in his first work. He should be satisfied to prove his work as carefully as possible until he knows that his eyes are to be depended upon for results which will harmonize with those given by the application of the tests. After this he must depend upon his eyes and his feeling for the fine results which distinguish art from industry. The student who does not use the tests until he has proven his ability to see correctly without them, or at least to obtain by sight results equal to those given by the application of the tests, acts very unwisely and will be compelled to spend much more time in acquiring his elementary training than he would if he chose to profit by the tests. My experience has shown that students who think it unnecessary to apply tests generally make a series of drawings of which the last is no better than the first, until they finally discover that the rest of the class have completed work which they are as far from doing as they were at the first of the year. At this time they generally decide to try the tests, and the result of such decision is often as surprising to the student as to the teacher ; for frequently I have known such students to make a drawing as false as possible, and the next day, after having seriously tried to follow directions and apply tests, to make a drawing which was quite true and satisfactory. The student must use tests in his first work, for in no other way can he learn how different appearances are from the facts, but he must aim to dispense with the blur glass and other mechanical means as soon |

Privacy Policy ...... Contact Us