ORNAMENTAL DECORATIONS

DECORATION is the science and art of producing beauty in ornament. Ornament, the product of purely decorative art, is always employed to beautify objects created for some purpose, independent of their decoration. It is truly an expression of love for the object —a desire to make it beautiful. It produces its legitimate effect when, without concentration upon itself, it makes the object to which it is applied more pleasing than if unadorned.

the very corner-stone of all good ornament. From this principle of fitness for its purpose there arises the fundamental law of ornament — subordination. This law requires THAT ALL ORNAMENT SHALL BE MODEST AND MODERATE, Strong contrasts and striking effects violate it. Illustrations of this requirement in matters of good taste in general are familiar to all. A loud voice in conversation is not excusable ; a forward, self-asserting manner is a mark if ill-breeding ; gaudy colors in dress are shunned ; showiness, or any other attempt to attract attention, is condemned. This requirement holds good in all ornament, whether architectural, domestic, or personal. He is not well dressed whose dress is conspicuous; that house is not well furnished where the furniture is obtrusive ; that building is not well ornamented whose decoration is not subordinate to the idea of the building.

Ornament has two sources — Nature and Geometry. In.the minds of many these are widely separated. Geometry is too often considered as simply a treatise on an assemblage of figures and forms which have no particular meaning except as a basis for mathematical study. Such a view is most inaddquate ; for geometry is really the study of ideal and typical forms, which while not discoverable in a perfect state in nature, are deduced by man from a study of nature.

Nature presents no ideal forms : these arc the result of man's thought led by nature. The forms of geometry are ideals conceived by man in " Thought's interior sphere," as archetypes of nature ; they are the forms toward which nature in evolution is constantly tending. Nature and geometry are, then, but different manifestations of the divine law. A thoughtful consideration of nature will show geometric plans and forms,

and modes of arrangement, in her handiwork. Order, symmetry and proportion are all exemplified in nature in varying degrees.

I. Geometric plans, enclosing figures and units.

2. Conventionalized units derived from natural forms as motives.

3. Historic ornament.

a. Geometric construction and symmetric arrangement.

b. The proper use of plant forms as motives.

c. Weil-selected examples of historic ornament.

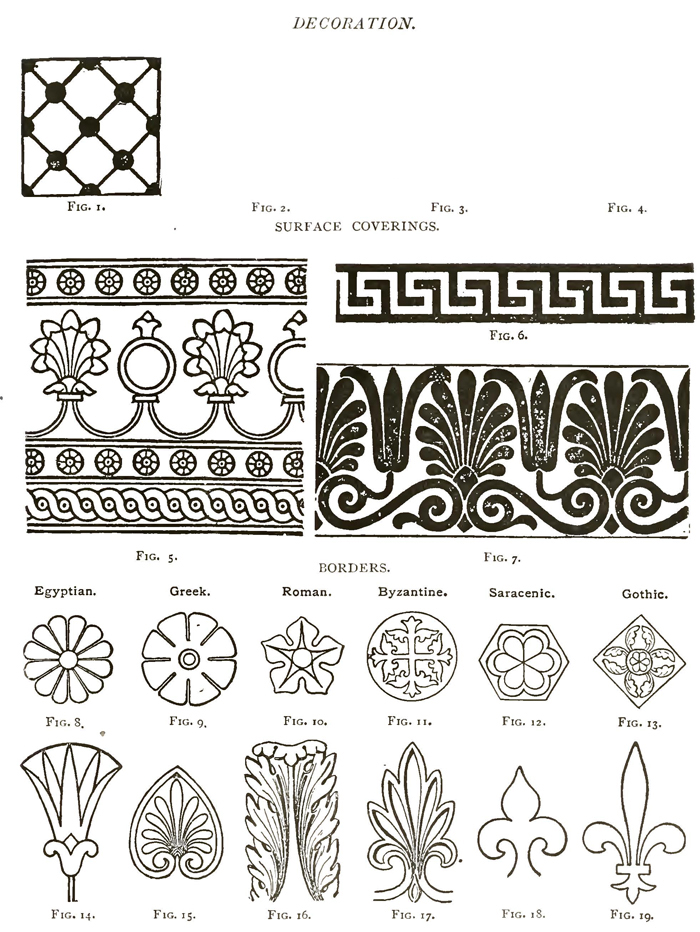

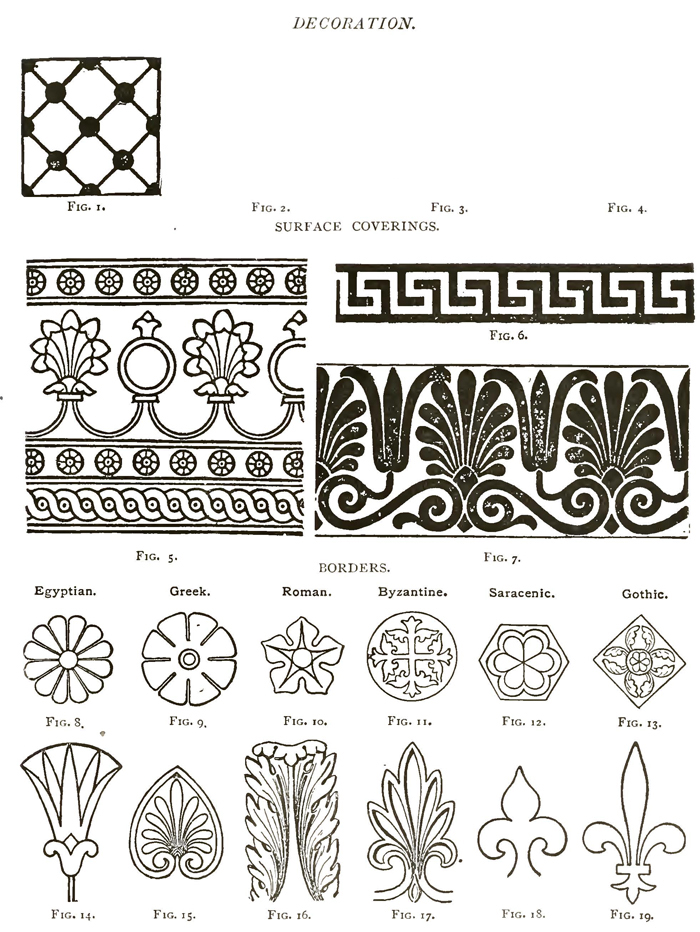

1. A surface design, to cover a surface, as in wall-papers, carpets, drapery and textiles in general.

2. A border, to limit a surface or a surface-covering.

3. A single arrangement, complete N itself, as in a bilateral unit, as the lotus and the fleur-de-lis, or as in a rosette or centre.

a. The enclosing figure.

b. The geometric plan, which embraces not only the general geometric outline, but also the lines and divisions required by order and symmetry for the construction of the design, — axes of symmetry and field lines.

c. The units or motives, which are repeated in making the design.

d. The ornament itself, or the filling.

e. The background or field.

The laws of growth, which are recognized and recognizable in all good ornament, are derived from the laws of growth in nature. It would be a mistake, however, to conclude from what has been said that a pictorial imitation of nature is good in ornament. A pic-• torial imitation of nature represents the accidents of growth. Order, regularity and symmetry are the normal laws of growth, while the irregular is accidental. This idea is developed in the treatment of conventionalization.

Flowers or other natural objects should not be used as ornaments, but conventional representations founded upon them, sufficiently suggestive to convey the intended image to the mind, without destroying the unity of the object they are employed to decorate. Universally obeyed in the best periods of art; crazily violated when art declines."

In all the best periods of art, all ornament was rather based upon an observation of the principles which regulate the arrangements of form in nature than on an attempt to imitate the absolute forms of those works, and wherever this Limit was exceeded in any art it was one of the strongest symptoms of decline."

We owe the beauty of nature the full tribute of our respectful appreciation, but we should never degrade her loveliness by putting it to unworthy service. The picture-painter throws his whole power into the attempt to reproduce natural truth ; but the designer, feeling the limitations of his materials, and the purpose to which his work must be applied, takes a different view, not because he appreciates nature less, but because appreciating it so much he cannot bring himself to do it discredit by inadequate representation.

We need scarcely say that any one attempting naturalistic work should have a good working knowledge of plant-structure, and even if he would hesitate to call himself a botanist, should be well acquainted with the leading laws of plant growth. A wild-rose spray, in all its picturesque beauty, is as much constructed according to law as the designer himself ; the spiral growth of its foliage, and the beautiful foreshortening, therefore, of the parts that result from this rigid Iaw, is as marked as any other law of nature; and it is no more permissible to add a sixth to the ring of five fragrant petals in each of its beautiful flowers than to consider it immaterial whether we put four, five, or six toes to the human foot."

" The imitation of natural objects for merely ornamental purposes usually disagrees both with the materials used and the place where they are introduced. It is also an indication of poverty of invention, and a deficiency of taste for design. In carpets, where roses and other flowers are figured, the very best rose is always unlike the reality, while the imagination is diverted from the general effect by the comparison of this imperfect copy with the natural flower. To obtain ideas for ornamental art, nature should be carefully studied and the beauties she presents should be fully understood, but she should not be directly copied in an unsuitable material."

" Experience proves that the fitting opportunity for realistic ornament very seldom occurs. It is for the most part contrary to the purpose or position of the object, ill adapted to the material and the method of working it, and most especially it is calculated to draw undue attention to the object, or, which is worse, to itself. A more subdued and reticent and altogether simpler style of design is almost invariably found to be advisable, either in the shape of pure ornament or in some adaptation of natural forms."

" The right method of studying nature does not consist in merely gathering her facts and applying them indiscriminately to any object as decoration, but in the endeavor to understand the principles upon which nature works, so that we may use her endless treasures with artistic wisdom. Moreover, by adopting this mode of studying nature we shall find that all the records of ancient art will have a new meaning for us."

" Ornament should be natural ; that is to say, should in some degree express or adopt the beauty of natural objects. Observe, it does not hence follow that it should be an exact imitation of, or endeavor in anywise to supersede, God's work. I t may consist only in a part adoption of, and compliance with, the usual forms of natural things, without at all going to the point of imitation; and it is possible that the point of imitation may be closely reached by ornaments which, nevertheless, are entirely unfit for their place, and are the signs only of a degraded ambition and an ignorant dexterity. Bad decorators err as easily on the side of imitating nature as of forgetting her, and the question of the exact degree in which imitation should be attempted under given circumstances is one of the most subtle and difficult in the whole range of criticism."

The subject of conventionalization is frequently misunderstood. Some, having a totally wrong impression of conventionalization, think of it only as a means of taking all the life and grace out of a leaf or a flower, and reducing it as nearly as possible to the hard lines of a geometric figure. This is a wholly wrong conception. True conventionalization is idealization ; it searches for the life and the marvellous manifestations of growth in the leaf or flower. Natural leaves are more or less unsymmetric ; a leaf type would usually be symmetric ; idealization rejects the occasional irregularity, and accepts the beauty of symmetry in the type form. Idealization seeks in the natural leaf for the beauty of symmetry, the beauty of general form, the beauty of radiation, — or, as it might be phrased, the beauty of stability — the beauty of proportion, the beauty of general curvature, and renders them in the idealized leaf. Every line of the conventionalized or idealized leaf can be traced as typical of the natural leaf.

Pupils should be led to seek for type forms of natural leaves by comparing many leaves of one kind, and to discover and express the peculiar beauty of each type form. This will be true conventionalization.

The purpose is entirely distinct from that of botanic study. In botanic study, the various parts and organs are studied with minuteness, and all the wonderful structure is revealed. In studying a flower for decorative purposes, the details are not taken up, unless for a special end ; but the general plan as to form is studied, and is rendered with faithfulness to the type form, and not to the individual.

Lead pupils as deeply as possible into the study of nature, in order that they may see for themselves the spirit of the plant which they are studying, as well as the more formal matter of arrangement. Then let them idea/the plant forms for use in ornament, by keeping the characteristics of growth, curvature and proportion, while simplifying outlines and omitting details.

In the past, many nations have produced certain ornament so repeatedly that the ornament has become characteristic of those nations. As the account of what nations have done is called history, so the ornament produced by nations is called historic ornament. Different nations have developed different kinds of ornament ; each kind, however, has a character or style of its own, hence styles of ornament are spoken of. The great historic styles are : the Egyptian, Greek and Roman, — the ancient ; the Byzantine, Romanesque, Saracenic and Gothic, — the middle age ; and the Renaissance, which may be called the modern. Among the ancient styles, the Assyrian and Persian are ranked as secondary, but they are coming more and more into prominence as new discoveries are made. The Persian, Indian, Chinese' and Japanese are called the Oriental styles. All of these would be taken up in a more advanced study of historic ornament.' The study of special styles is begun in Book 7, and pursued in the order given above. This will lead to an appreciation of the characteristics of each style as well as of the influences which formed the style. As the study progresses, the interrelation of these styles will be seen.

The beauty produced by fine proportioned and delicately contrasted spaces should be emphasized in all study of historic ornament. The gradual training of the eye and the mind to a fine appreciation of this important element will lead the pupils to a right understanding of what constitutes good work, and will ultimately express itself in their creative efforts. The study of historic ornament as one proceeds leads to its interpretation as a visible manifestation of the history, life and spirit of the people who produce it. The contact of various nations or peoples, either through war, commerce or travel, can be traced in their ornament ; and it is an evidence in the various phases of progress and civilization.

Good historic ornament is always ennobling, for it is an expression of the best and most enduring feeling ; it is, in a very high sense, "a survival of the fittest." A lesson in historic ornament may and should be not merely a lesson in drawing, but also, to a greater or less degree, a lesson in history and aesthetics, in living and in doing.

Historic ornament serves as a broad field for the discovery of those elements which make for beauty in decorative art. The study of good examples of ornament leads to the development of certain general principles. It is found that unity is essential to the production of beauty in ornament. Unity requires that the effect of a design, as a whole, should be considered, and that the parts should be subordinate to the whole effect.

The leading principles which through unity lead to the creation of the beautiful in decorative design may be stated as —

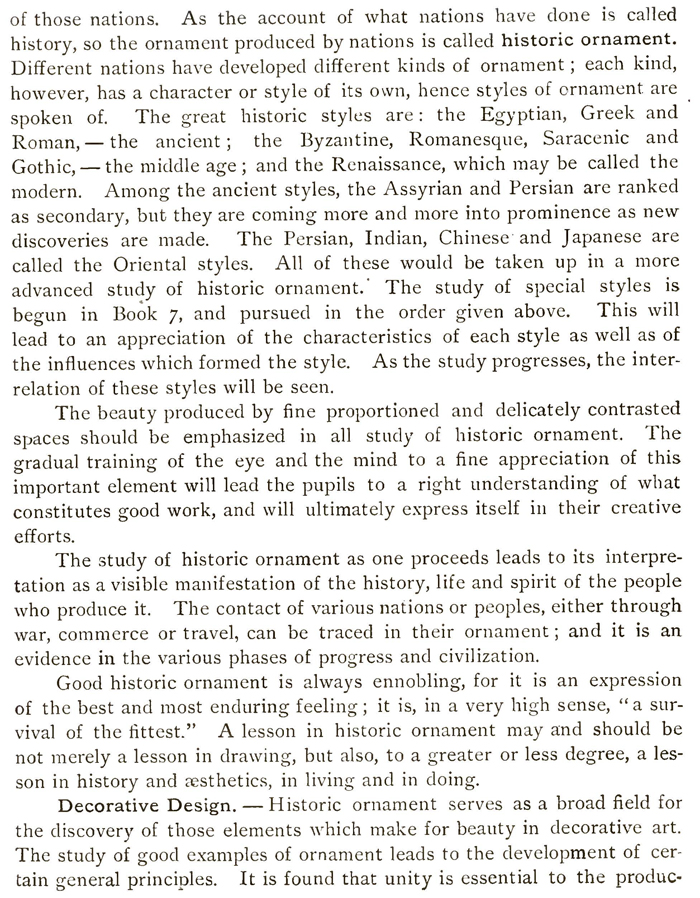

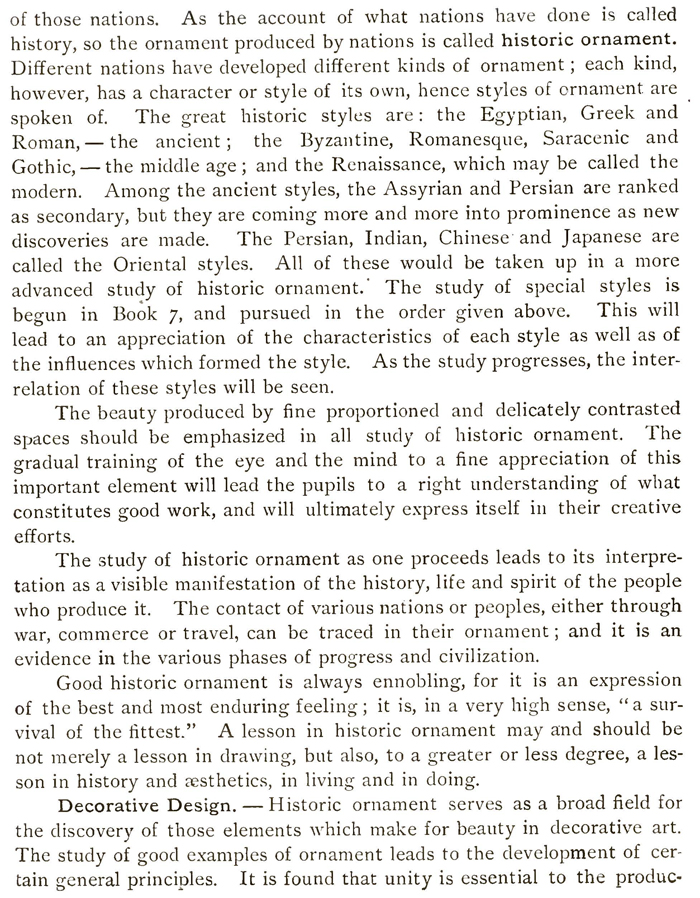

Symmetry is produced by balancing the parts one against another. The balance may be of form (page 29) or of value (Antae, Temple of Eleusis illustrated below). Figures may be bi-symmetric or multi-symmetric ; in other words, there may be symmetry on an axis (Figs. 8-13) or about a centre (Figs. 14-19).

it As in every perfect form of architecture a true proportion will be found to reign between all the members which compose it, so throughout the decorative arts every assemblage of forms should be arranged on certain definite proportions; the whole and each particular member should be a multiple of some simple unit of proportion."

The units of a design must not be too small in proportion to the ground to be covered. 1 he ornament or filling should, as a general rule, occupy about two-thirds of the space within the enclosing figure. Color as well as space values should, however, be carefully considered as modifying elements.

As the effect of rhythm in music is produced by the regular recurrence of measures of time; in decoration, it is produced by the regular repetition of the parts of a design. There are three ways of repeating units of design: (1) to cover a surface ; (2) on a straight line ; (3) around a centre.

Repetition may be close or open, simple or alternate. In close repetition, the units touch each other; in open repetition, a space intervenes. In simple repetition, one unit only is repeated. In alternate repetition, two or more units are repeated, one alternating with the other. Counterchange and interlacing are forms of alternate repetition.

Order, so essential to the beauty of a design, depends upon a definite plan of geometric arrangement. This plan is secured by enclosing forms, axes of symmetry, and field lines for the units.

From Antm, Temple at Eleusis.

In a decorative design, there should be a pleasing contrast of direction or directness in line, of proportion in space, of shape in figures, of tone and hue in color.

Color may be produced by the brush, by colored paper, or in a representative way by half-tone. Half-tone is produced with the pencil or pen by covering the surface evenly with lines or by pencil painting, and may be employed to distinguish the ornament from its background (page ). Half-tone may be used, either upon the background or the ornament ; whichever covers the least surface should be in halftone. When there is more half-tone than white surface, the design is likely to appear heavy. Mechanical results are not desirable in half-tone in freehand work.

There is great beauty in that intricacy of form produced by subtility of proportion and curvature. The simpler the proportion, and the more easily it is detected by the eye, the less pleasing is the effect ; while the more subtile the proportion, and the more difficult it is for the eye to make it out, the more pleasing is the effect. So, also, the more subtile of two curves affords the eye the greater pleasure. Compare the circle and the oval.

There is much more beauty in the simple arrangement of good, well-drawn figures, having a large proportion to the surface which has to be covered, producing a certain strength or breadth of effect, than in a. profusion of complicated details on a small scale. If there are subdivisions of units, they must be made subordinate to the effect of the unit as a whole.

The union of parts produces stability. In a surface design, this union is secured by its enclosing figures : in a border, by its marginal lines ; in a rosette, by a strong central figure or a tendency toward the centre.

It is essential that there should be repose in ornament ; that is, there should not be too violent contrasts of form or of color in the parts, but they should harmonize while they vary.

Curved lines should unite tangentially with curved or with straight lines. Tangential union showing laws of growth is a simple example of harmony. See page 35.

By observing plant forms and tree growth, it will be seen that in a general way plant growth falls into three classes as to direction — erect, as in trees and shrubs (under this head may also be placed ascending growth, rising obliquely from the root) ; twining or climbing, as the morning glory, the pea, bean and nasturtium; the running or creeping, as the strawberry. Erect growth is suggestive in its vertical symmetry for bilateral units in ornament, and in the radiation seen in the top view for arrangements about a centre. The twining or climbing plants suggest spiral growth in ornament and the running plants give motives for horizontal ornament and for a garland treatment.

The law of tangential union, always observed in nature, should govern decorative design. Owen Jones states this law thus : All junctions of curved lines with curved, or curved with straight, should be tangential to each other," or, in other words, they should be so drawn that they would touch, but if produced would not cut each other. Owen Jones further says : "Oriental practice is always in accordance with it. Many of the Moorish ornaments are on the same principle which is observable in the lines of a feather and in the articulations of every leaf ; and to this is due that additional charm found in all perfect ornamentation, which we call the graceful." it may be called an example of harmony of form. The suggestion here given of the interrelation of beautiful form and music opens a wide door.

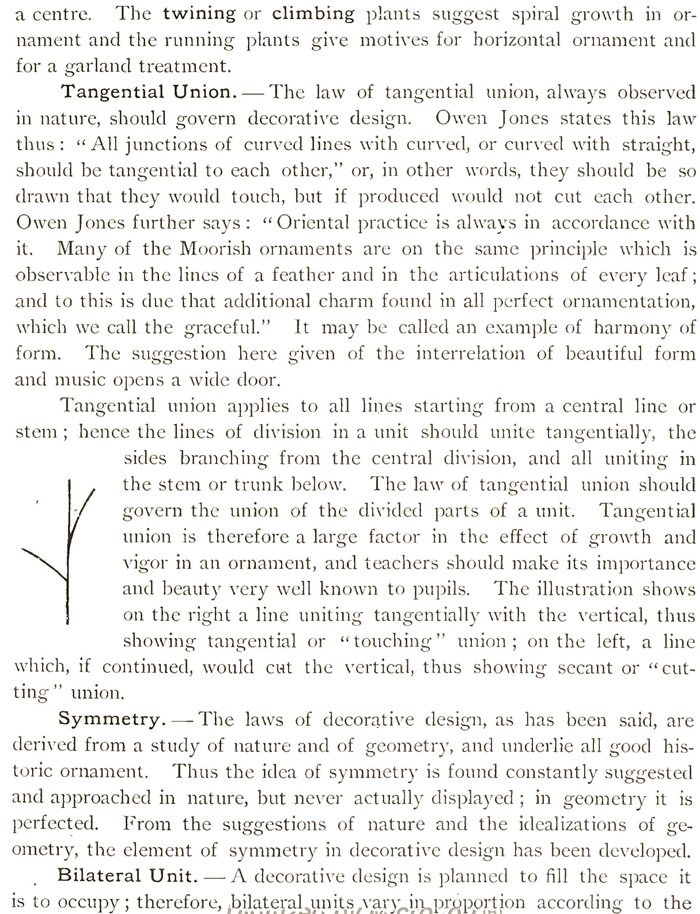

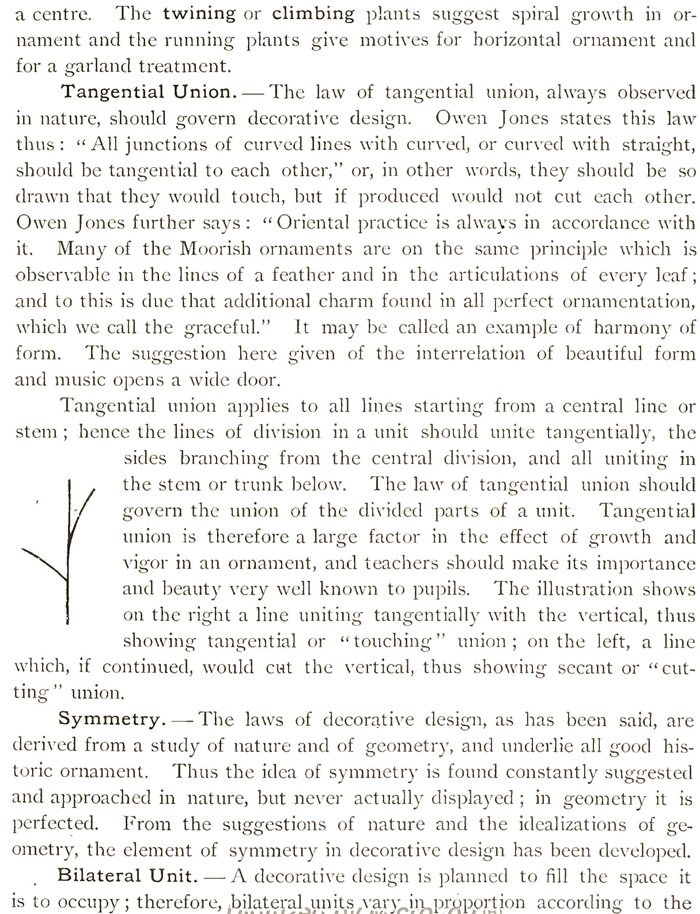

Tangential union applies to all lines starting from a central line or stem ; hence the lines of division in a unit should unite tangentially, the sides branching from the central division, and all uniting in the stem or trunk below. The law of tangential union should govern the union of the divided parts of a unit. Tangential union is therefore a large factor in the effect of growth and vigor in an ornament, and teachers should make its importance and beauty very well known-to pupils. The illustration shows on the right a line uniting tangentially with the vertical, thus showing tangential or "touching" union ; on the left, a line which, if continued, would cut the vertical, thus showing secant or "cutting" union.

The laws of decorative design, as has been said, are derived from a study of nature and of geometry, and underlie all good historic ornament. Thus the idea of symmetry is found constantly suggested and approached in nature, but never actually displayed ; in geometry it is perfected. From the suggestions of nature and the idealizations of geometry, the clement of symmetry in decorative design has been developed.

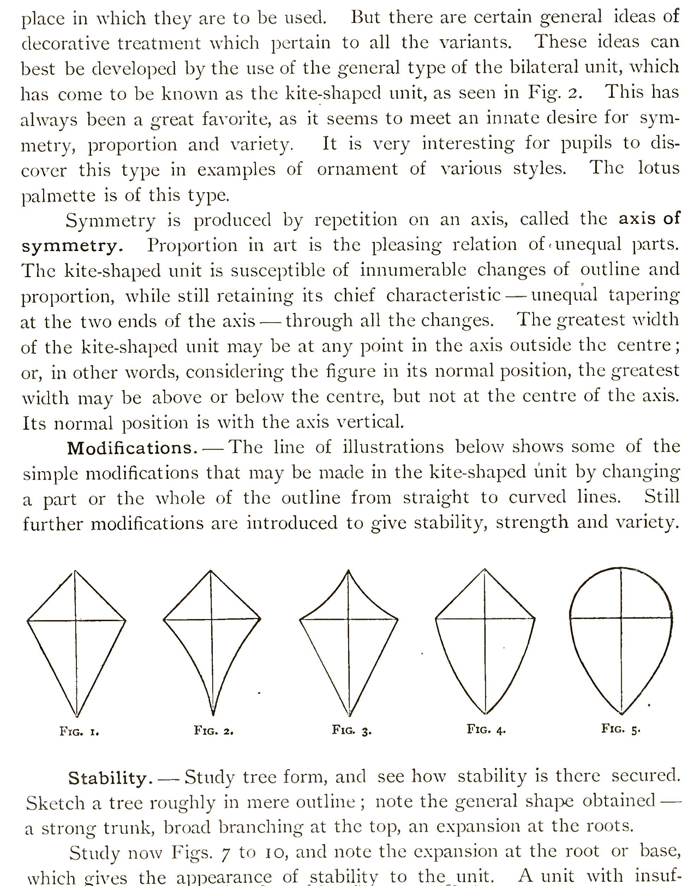

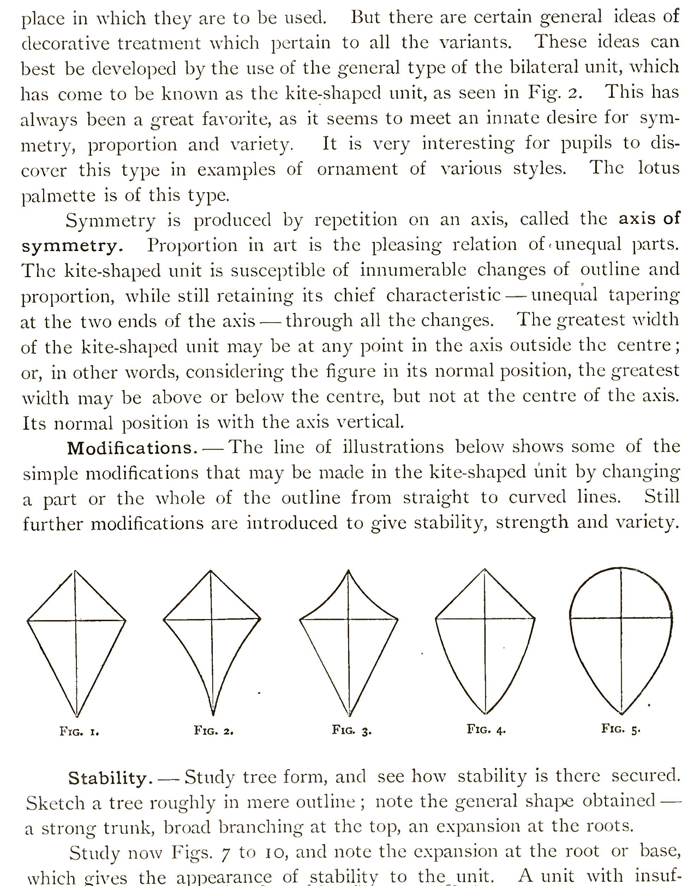

A decorative design is planned to fill the space it is to occupy; therefore, according to the place in which they arc to be used. But there are certain general ideas of decorative treatment which pertain to all the variants. These ideas can best be developed by the use of the general type of the bilateral unit, which has come to be known as the kite-shaped unit, as seen in Fig. 2. This has always been a great favorite, as it seems to meet an innate desire for symmetry, proportion and variety. It is very interesting for pupils to discover this type in examples of ornament of various styles. The lotus palmette is of this type.

Symmetry is produced by repetition on an axis, called the axis of symmetry. Proportion in art is the pleasing relation of ,unequal parts. The kite-shaped unit is susceptible of innumerable changes of outline and proportion, while still retaining its chief characteristic—unequal tapering at the two ends of the axis — through all the changes. The greatest width of the kite-shaped unit may be at any point in the axis outside the centre ; or, in other words, considering the figure in its normal position, the greatest width may be above or below the centre, but not at the centre of the axis. Its normal position is with the axis vertical.

The line of illustrations below shows some of the simple modifications that may be made in the kite-shaped Unit by changing a part or the whole of the outline from straight to curved lines. Still further modifications are introduced to give stability, strength and variety.

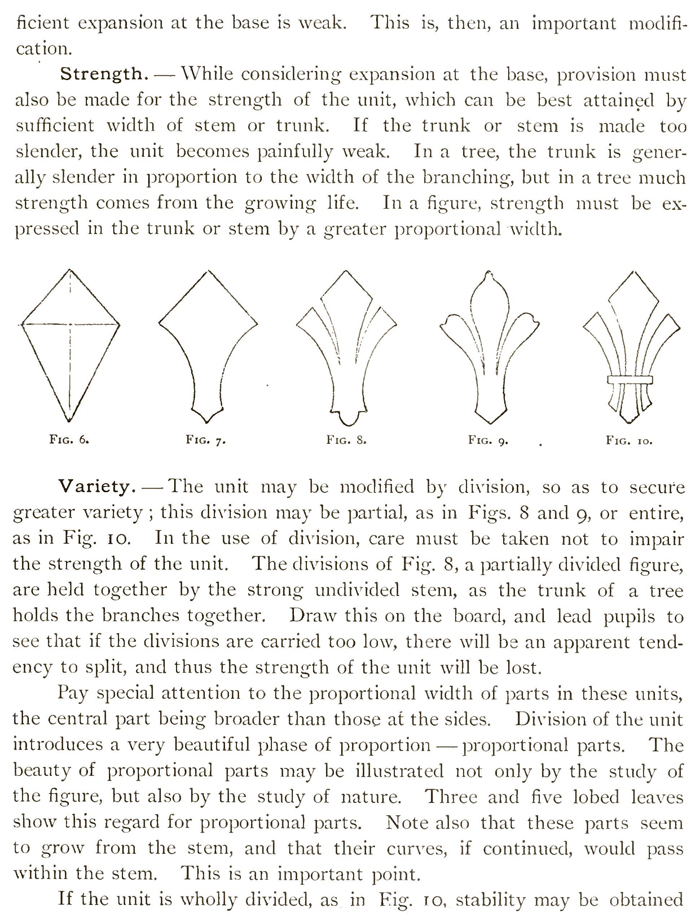

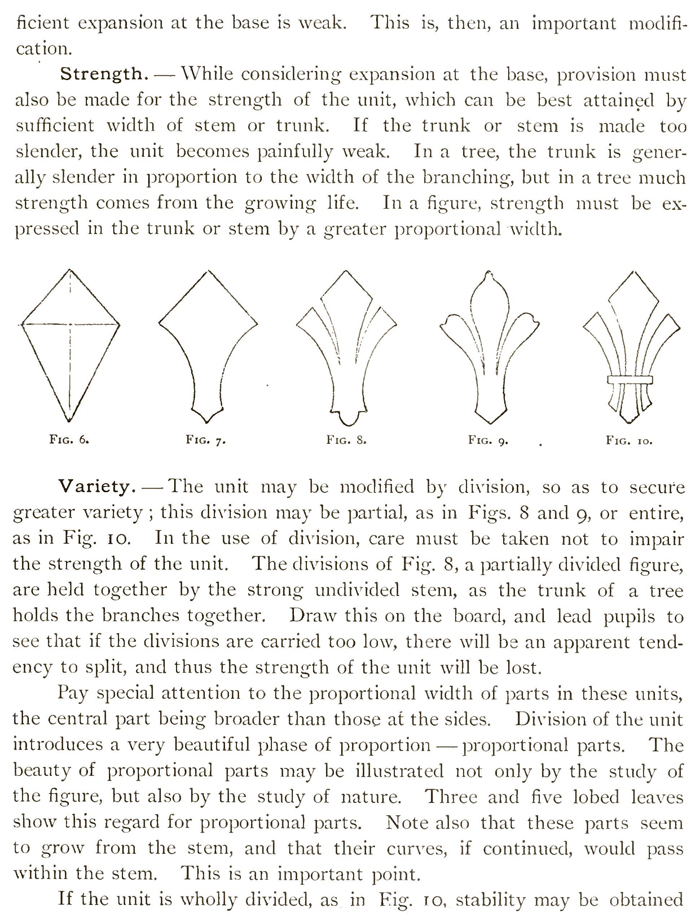

Study tree form, and see how stability is there secured. Sketch a tree roughly in mere outline ; note the general shape obtained —a strong trunk, broad branching at the top, an expansion at the roots.

Study now Figs. 7 to so, and note the expansion at the root or base, which vives the appearance of stability to the unit. A unit with instil

by holding the parts together by a band. Care must be used, however, to to place the band at the narrowest part of the unit, where it would really be of use. Show this by drawing on the board. The good effect of fine curvature and pleasing proportion may be largely destroyed by placing the band above or below the narrowest part of the unit. The effect given is that of insecure holding, which detracts greatly from the repose necessary in ornament. Division may also be used in a moderate degree to give variety to the base.

It is not an easy matter for beginners to draw simple and beautiful units., and teachers are sometimes at a loss to know how to help their pupils. It is necessary first to consider the characteristics of a good unit. A omit complete in itself should possess symmetry, proportion, contrast, breadth, stability, and repose, and should be judged according to its possession or lack of these characteristics.

Symmetry. — Is the unit symmetric, or is it one-sided? Pupils should be led to see the beauty of symmetry, by which one part is the reflex of the other, and therefore in harmony with it.

Proportion.— Is the proportion of the unit agreeable as to general dimensions ? The effect will not be good if the two dimensions are either very nearly alike or widely different. lf the unit is partially divided, what is the relative proportion of its parts? There should be a moderate inequality between the central part and those at the side, the central part being larger than the other two. The proportion of each part should be that of slenderness, rather than of breadth. If the parts are made too wide, the unit, as a whole, will lack elegance of proportion.

Contrast.— Is there a pleasing contrast of straight and curved lines, or of inner and outer curves, or of curves and points? There is often a monotony of outline in a unit, produced by several curves of the same sort, or by continuous curves of no very strong character.

Breadth.—Is the unit simple? Simplicity is a great beauty in decoration, If the unit is cut up into many petty parts, this beauty is lost.

Stability.— Is the stem of the unit broad enough to be strong? Does the unit expand at the base? if partially divided, would the curves of each part, if extended downward, pass within the stem, or would they cut through it? To be true to the laws of growth, they should pass within the stem. The curves which divide the unit into three parts would, if continued downward, cross the outer lines of the stem. If wholly-divided and held by a band, is the band so placed that it can perform its office?

Repose.— Is there anything startling about the unit ? Has it mani sharp points ? or unusual curves? If so, it cannot be restful. Are th:.. curves easy, flowing, and graceful? The higher qualities of repose are obtained through symmetry, proportion, breadth and stability.

Rosette. —A rosette may or may not have an enclosing figure. When it is desired for any reason to call particular attention to the shape of a rosette, or to indicate more clearly its fitness to occupy a certain place, an enclosing figure is added to emphasize the shape. A rosette is usually made up of symmetric units, which occupy equal fields. A field is that :art_ of the ground of a design that a unit is to occupy. If the rosette is from a flower form the number of units is determined by the petals in the flower chosen. To aid in preserving the symmetry and order of the rosette, the axis of the units should be drawn. In a circular figure, the radii of the circle will serve as axes of the units.

The unit, however, must not touch the enclosing circle, for that would give a crowded look ; a feeling of restriction and constriction would ensue, and the repose of the figure would be lost. A space, therefore, should be left between the ornament or filling and the enclosing figure ; at least two-thirds of the ground should be filled. A skilful teacher will lead pupils to this study of space relations.

Study a flower, observe its general outline, the arrangement about the centre, the radiating petals, their graceful shape, the way in which they are held at the centre, the stamens and pistils filling the centre. Try to express this in a broad, simple way, by drawing with an even line. You will have a rosette with regular radiating 'units of beautiful outline, and a strong, simple centre. The details of stamens and pistils are too minute for representation here — the result would be only clots, which would seem characterless. The centre of the rosette, holding the units together, is simply a reflex in the drawing of that mysterious power of life that sends out the flower and holds the petals with a circling hand. This is a delightful exercise, and is always enjoyed by pupils, as it is not beyond their comprehension, and it gives them an opportunity to discover the elements of beauty ; and so insight grows.

Besides the wonderful beauty of appearance and the marvellous physical structure of a flower, there lies within it a perfect manifestation of order, of symmetry, of proportion, of unity, of esthetic beauty. The esthetic is the highest type of the ideal. In studying a flower for a motive of ornament, the attempt must be, through the study of the flower, to reach its ideal.

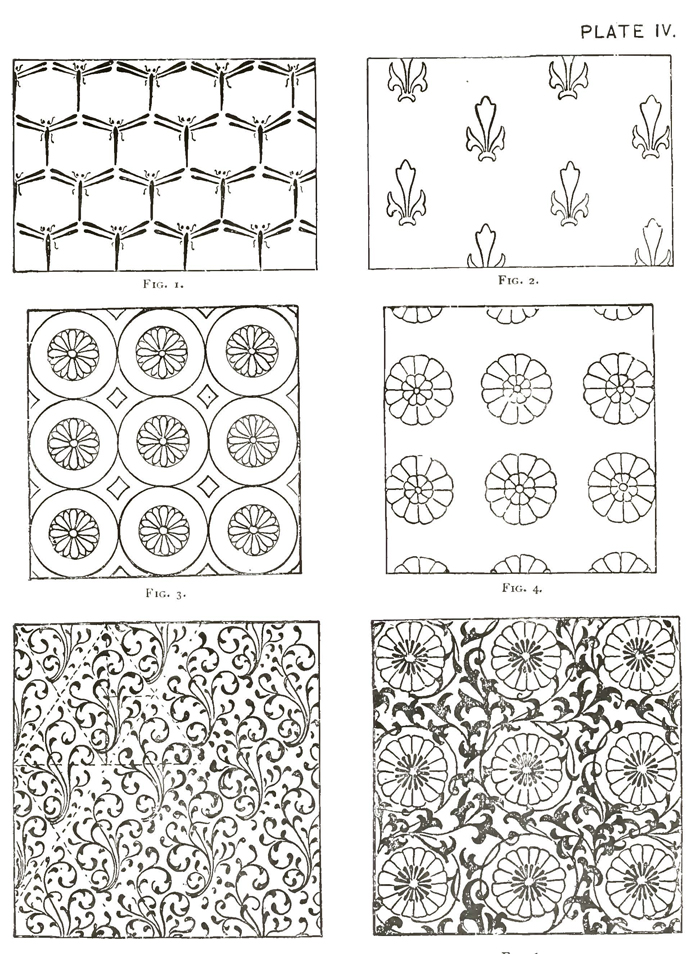

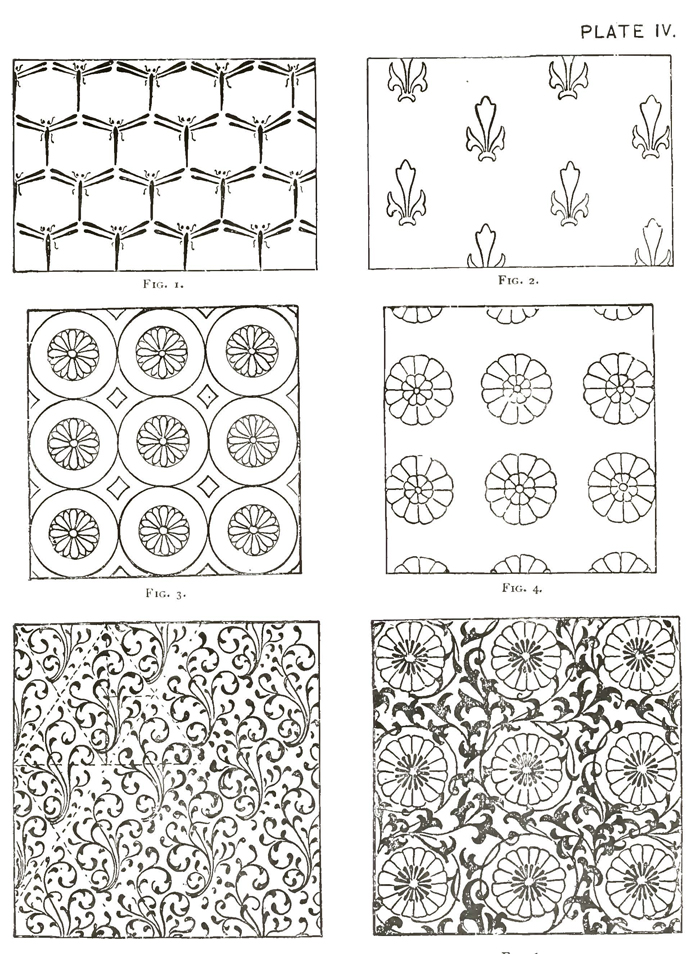

A Surface Covering. — Probably the idea of designs for surface covering arose from the patterns brought out in weaving. Thus from the beginning order was suggested ; and still, order resulting from a geometric plan is one of the essentials in a surface covering.

The first step then in the actual drawing of a design must be a plan on which to lay it out. It must be determined also whether it is to be used horizontally or vertically. A bilateral unit is always suitable for a vertical surface covering. A rosette is suitable for either a vertical or a horizontal surface covering.

Have some examples of simple surface covering in textiles or wallpaper, and let pupils discover the geometric arrangement or plan that underlies the placing of the figures. Sometimes this plan is easily traced, and sometimes it is apparently hidden ; but a little searc.'1 will always find it. The usual plans of surface coverings are based on squares, rhombuses, or hexagons repeated. .

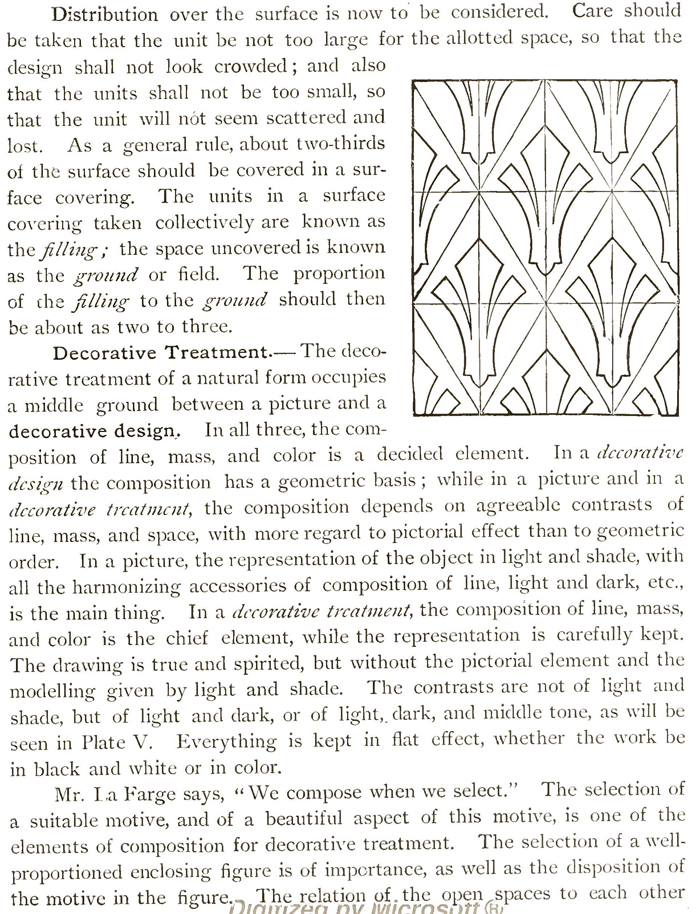

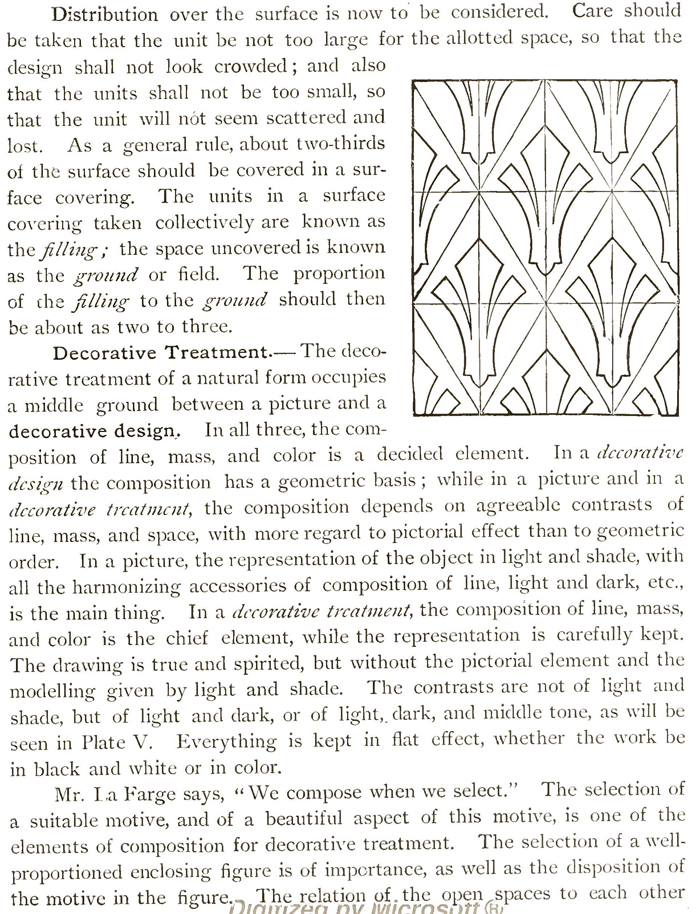

In some of these designs, the geometric plan shown by light lines in Fig. 5, Plate IV, does not appear in the finished work ; only the decorative figures remain. In others, as in Fig. 3, the geometric plan is left to form part of the design. Plate IV gives various examples of surface coverings which plainly show geometric plan. Fig. i is Japanese ; Fig. z is Persian ; Figs. 3 and 4 are Egyptian ; Figs. 5 and 6 are modern, and were taken from Lewis Day's Anatomy of Pattern.

When in a surface design the units only appear, the geometric laying out of the space having been erased, the arrangement is techn'-ally known as powdering. Figs. 2, 4, 5 and 6, Plate IV, are examples of powdering.

Distribution over the surface is now to be considered. Care should be taken that the unit be not too large for the allotted space, so that the design shall not look crowded ; and also that the units shall not be too small, so that the unit will not seem scattered and lost. As a general rule, about two-thirds of the surface should be covered in a surface covering. The units in a surface covering taken collectively are known as the filling; the space uncovered is known as the ground or field. The proportion of the filling to the ground should then be about as two to three.

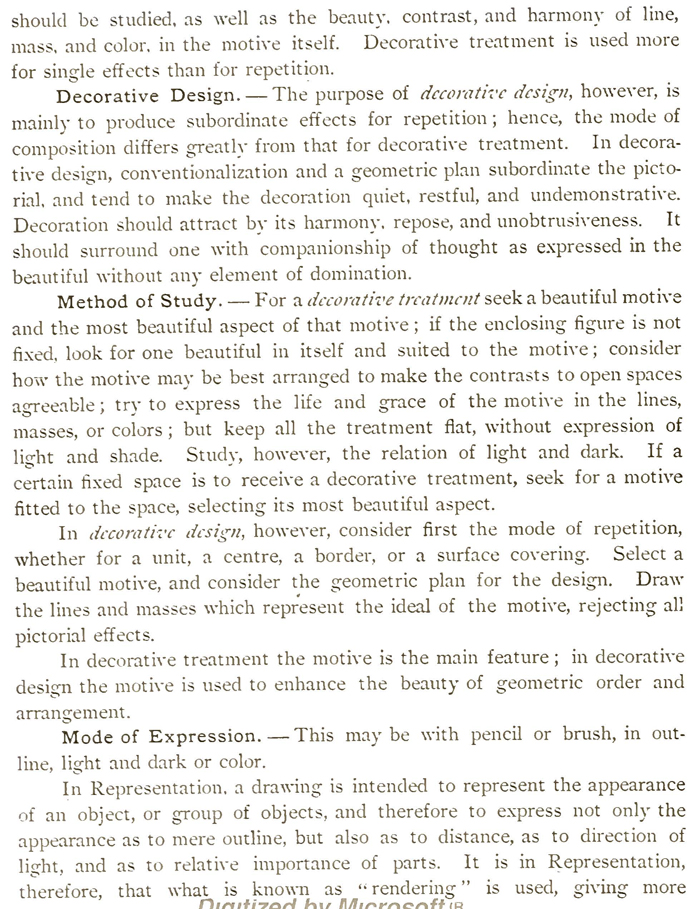

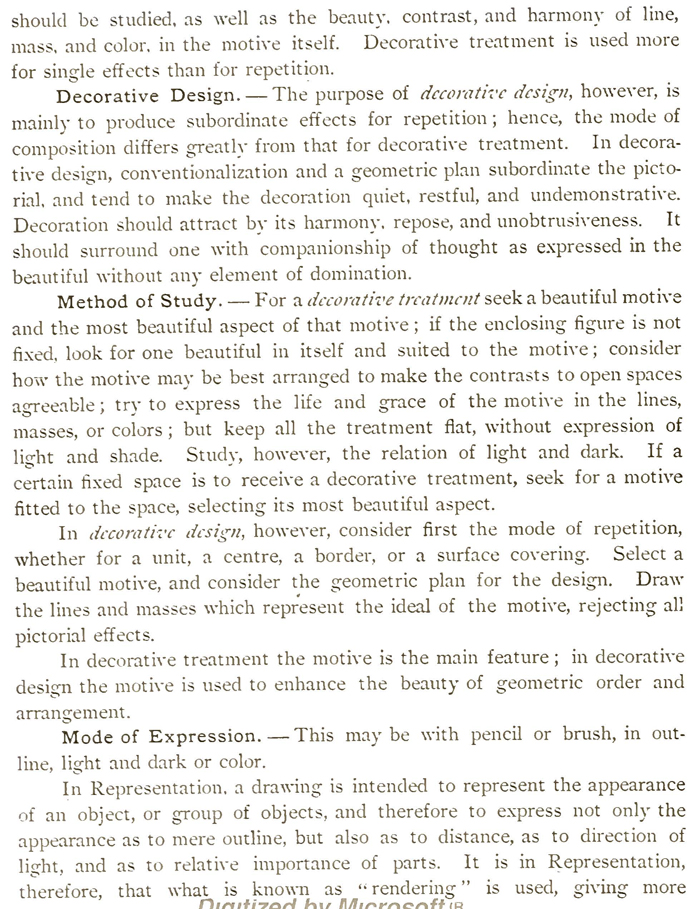

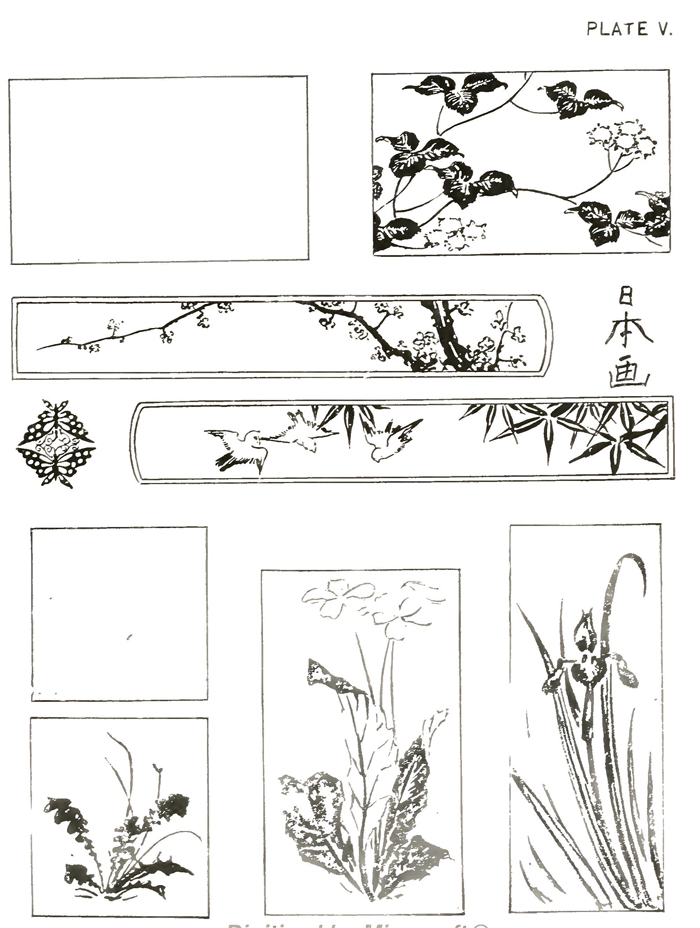

The decorative treatment of a natural form occupies a middle ground between a picture and a decorative design. In all three, the composition of line, mass, and color is a decided element. In a decorative design the composition has a geometric basis ; while in a picture and in a decorative treatment, the composition depends on agreeable contrasts of line, mass, and space, with more regard to pictorial effect than to geometric order. In a picture, the representation of the object in light and shade, with all the harmonizing accessories of composition of line, light and dark, etc., is the main thing. In a decorative treatment, the composition of line, mass, and color is the chief element, while the representation is carefully kept. The drawing is true and spirited, but without the pictorial element and the modelling given by light and shade. The contrasts are not of light and shade, but of light and dark, or of light,. dark, and middle tone, as will be seen in Plate V. Everything is kept in flat effect, whether the work be in black and white or in color.

The selection of a suitable motive, and of a beautiful aspect of this motive, is one of the elements of composition for decorative treatment. The selection of a well-proportioned enclosing figure is of importance, as well as the disposition of the motive in the figure opens spaces to each other emphasis to some parts and less to others, according to their light, their distance, and their value, by lines varying in thickness and in shade.

In Decoration the purpose is different. No effect of light, shade, distance, or value is desirable in flat decoration. A decorative figure should be drawn in the simplest possible way. It should be drawn with intelligence, with strength, with purpose, with firmness. The line should be open in texture, of an even gray color, and of an even width. Venation may be expressed (it should be sparingly, however) by a line tapering in width. Unevenness of line in decorative outline detracts from respose.

that is, the line rendered as it would be in pictorial drawing — is out of place in flat decoration. The line may sometimes be irregular, as in the drawing of historic ornament, but it should retain the effect of flatness. Lead pupils during their study of ornament to the discovery of the principles which have been given and to the use of them in decorative design. Decorative design is closely akin, in many ways, to music : it has rhythm and accent through repetition, melody through curvature and color, and harmony through proportion and relation of parts to make a " perfect whole." It will not be difficult for a teacher to make these analogies apparent. All art is one, whether of word, form, sound, or color.

The subject of Decoration opens a wide field for creative power—for the expression of the individual. Gradually the pupils should be led through sequential exercises involving modes of arrangement, space relations, and distributions as well as the study of fine examples of ornament, to the expression of his own ideas of the beautiful in terms of art.

Mere acquisition, whether of money, knowledge, culture or zesthetics, is selfish ; and all selfishness is barren. Whatever the subject may be in education, it should aim to ultimate in productive power through creative activity.

In the subject of Representation, you aim to reach this end not only through practice in drawing the appearance of objects and study for its principles, but also through Representative Design or pictorial composition. So in the subject of Decoration, aim to increase the productive

power of the pupils, not only through a study of Historic Ornament for its beauty and for the elements that go to make up that beauty, but also through exercises Decorative Design. Thus creative activity, stimulated and enriched by the study of the beautiful in ornament, will ultimate in productive power.