Home > Directory Home > Drawing Lessons >Pencils Drawing > Art Materials Needed

ELEMENTARY pencil drawing techniques : Simple ways to draw with pencils

|

GO BACK TO THE HOME PAGE FOR PENCIL DRAWING TUTORIALS

[The above words are pictures of text, below is the actual text if you need to copy a paragraph or two]

ELEMENTARY TECHNQUES FOR PENCIL DRAWING

ONE of the first things the student must bear in mind is that the art of drawing in lead pencil is a fine art needing the most delicate application. It must be approached from the first with care and sympathy. There is less possibility of manipulating the stroke, to correct even the smallest mistakes, than there is in watercolour, where the pigment may be manipulated to some extent while still wet. Of course, pencil strokes may be erased, but when they are placed in close work among other strokes erasure results not only in injury to the adjacent lines but also in a loss of the crisp quality which , is so much to be desired. The delineation of every stroke will at once convey the temperament of the draughtsman, and no amount of subsequent overshading or touching up can make a good drawing out of one that was, in the first place, bad. Although it has been pointed out that in this medium it is easy to erase work, yet from the very beginning promiscuous rubbing out must be avoided.

However simple an object the student wishes to depict, the pencil should be held correctly in a position similar to the orthodox position for holding a pen. Thought should be exercised as to exactly what is required to be done and how it should be carried out. In fact, in the early stages every stroke commenced should be made with deliberation. Successful flashing of the pencil over the paper is only achieved after much experience has enabled the student to triumph over the peculiar difficulties of rapid work, which requires great confidence and precision of touch. Before even the smallest sketches or drawings are attempted many elementary exercises should be carried out in order that the student may become familiar with the nature of the medium, and thus realize what can be expected of it, as well as its difficulties and limitations.

Lead pencil lends itself to shading and modelling more particularly than any other medium applied with a point, but this should not tempt the student to indulge in shading before some mastery of drawing in outline has been gained.

The observations in Chapter VIII explain how the force of form can be conveyed by line or silhouette even without modelling and, in the first stages, a practice should be made of trying to convey the appearance and nature of objects by line alone, for a sound training in line drawing is indispensable if highly finished successful lead pencil work is ever to be accomplished.

Even the most highly finished and most elaborate art in colour is but a convention at the best, as it is merely the representation on a flat surface of objects drawn to appear as if they were in the solid. It is a medium for presenting what is perceived by the artist that this may be comprehended and enjoyed by others. But it is in regard to drawing in line that art is even more a matter of convention. Drawing in outline is perhaps the oldest and most simple of all methods of depicting ideas and objects.

In regard to technique it must, from the first, be remembered that the line is essentially a convention because it does not exist in reality. It must only be considered as depicting the boundary between different tone values, or what may be loosely termed the edge of shades, and when drawn should be thought of in this way. Also as the work becomes more advanced and approaches what may be termed " highly finished work," the hard line, unless it is especially retained and accentuated for decorative effect, should gradually be eliminated. At the same time realism must not be carried to such an extent that the charm of the technique or the manner in which the drawing has been rendered is lost.

All teachers of drawing emphasize the need of first acquiring a facility for drawing in outline. Among modern masters Mr. Harold Speed, in his most valuable book The Practice and Science of Drawing, offers advice and arguments which every student should study with reverence. He places drawing in line as the primary need and lays stress upon the necessity for " hard application " and " searching accuracy " throughout the period of training. The early portions of Ruskin's " Elements of Drawing " may also be studied with advantage by all who hope to learn to draw in lead pencil.

Ruskin is, of course, emphatic upon the need for observation and for trying to depict, even in outline, things not as types but rather each as an exception to its type.

There are many drawings in outline by both old masters and modern artists which are full of truth, force and satisfying appeal. The student, therefore, will find nothing more helpful than to commence his study by the drawing of simple outlines. Lines, just lines, should at first be practised ; short lines, long lines, simple objects and so on. Endeavour to draw lines that have character, and not mechanical lines. The difference is that which no amount of explanation can convey; it is a very subtle difference, which is priceless and unteachable, and will come to the student only by practice with discernment. Lines must be drawn with one movement only. They should not be dragged out in a hesitating way. As Ruskin says, " If you want a continuous line your hand should pass calmly from one end of it to the other." Practise this, and if in the first lesson the student achieves so much he will have learned an essential which will give an added value to all his subsequent work.

The next step is that of curved lines. If these curved lines are to be strictly geometrical the step is a very long one. The drawing of circles and ellipses is generally advocated as the second step, but it seems unwise, for without instruments it is never possible to draw perfect geometrical shapes, and the ugly shapes which the student will at first produce when endeavouring to draw circles are discouraging.

Circles and ellipses are less needed in general drawing than curves which are either parts of or approximate to parabolas. The parabola is the most beautiful of all shapes that can be set up mechanically, and is really the merging of geometric curves into curves which are not possible of mathematical determination. Before drawing circles, ellipses, and round objects seen in perspective, parabolic curves should be practised, natural objects being used as models.

* The student, armed with a small block of cartridge paper and HB pencil, may with advantage recline on a bank of thickly growing grass, and, looking among the labyrinth of blades, choose a little group and practise drawing their curvilinear form and intersections. Fig. 9 illustrates what might be done in this way. There is a wealth of interest and value to be derived from even so simple a study.

* The following is a quotation from " The Curves of Life," by Theodore Andrea Cook, which may be of interest to the student at this stage : " The application of the spiral to organic forms results in the discovery that nothing which is alive is ever simply mathematical . . For instance, the nautilus only approximates to the logarithmic spiral." He says " The theory may also be applied to art; nothing that is mathematically correct can ever exhibit either the characteristics of life or the attractiveness of beauty."

Beyond that of gaining dexterity in the drawing of curved lines, there are other things to be learnt during this simple exercise.

There is the judgment and placing of forms in relationship to each other. There is also useful practice not merely in drawing lines, but after stopping them short (where the blades of grass cross each other), in continuing the line again in the same direction, maintaining the same power and tone.

This, too, serves as a simple exercise in truthful observation, for it is not only grass that should be depicted, but the kind of grass and its condition. To quote again from Ruskin : " The grass may be ragged and stiff or tender and flowing, sun-burnt and sheep-bitten or rank and languid, fresh or dry, lustrous or dull ; look at it and try and draw it as it is, and don't think how somebody told you to draw grass." Such points of peculiarity and character should be indicated in the lines which define the blades, so that from the first the student shall come to see the value of giving life and truth to his drawings.

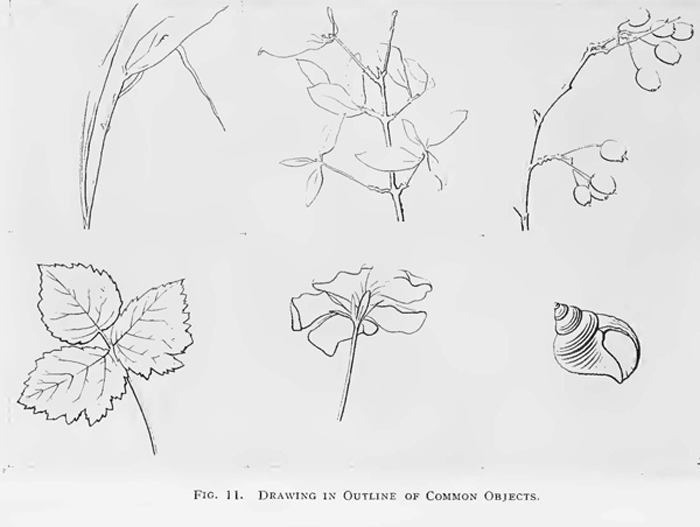

DRAWING IN OUTLINE OF COMMON OBJECTS.

Similar studies to the above, each demanding increasing facility, should be made, and for this purpose the drawing of leaves, flowers and plant forms, twigs and shells cannot be bettered. The figure indicates what is suggested.

The need for drawing circular and elliptical forms is thus more gently and naturally approached.

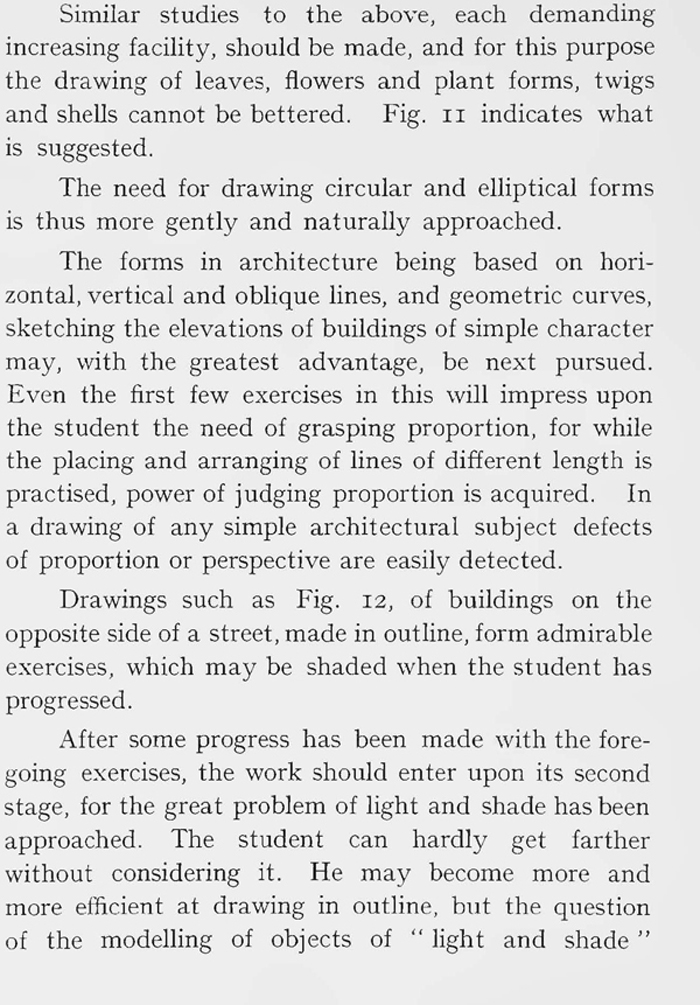

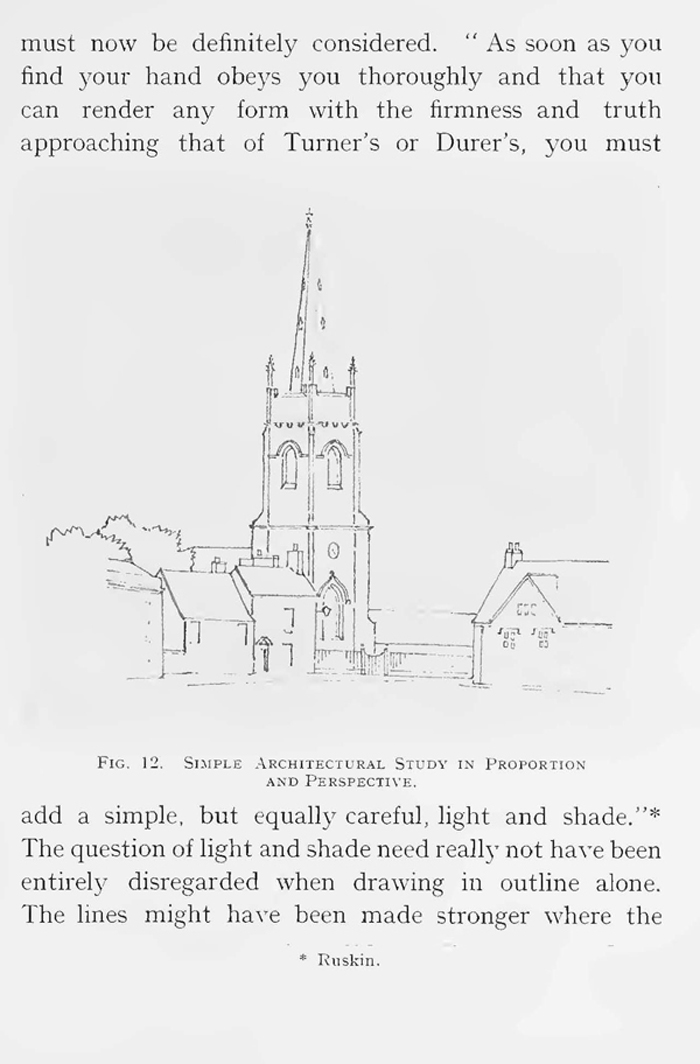

The forms in architecture being based on horizontal, vertical and oblique lines, and geometric curves, sketching the elevations of buildings of simple character may, with the greatest advantage, be next pursued. Even the first few exercises in this will impress upon the student the need of grasping proportion, for while the placing and arranging of lines of different length is practised, power of judging proportion is acquired. In a drawing of any simple architectural subject defects of proportion or perspective are easily detected.

Drawings such as Fig. 12, of buildings on the opposite side of a street, made in outline, form admirable exercises, which may be shaded when the student has progressed.

After some progress has been made with the foregoing exercises, the work should enter upon its second stage, for the great problem of light and shade has been approached. The student can hardly get farther without considering it. He may become more and more efficient at drawing in outline, but the question of the modelling of objects of " light and shade " must now be definitely considered. " As soon as you find your hand obeys you thoroughly and that you can render any form with the firmness and truth approaching that of Turner's or Durer's, you must add a simple, but equally careful, light and shade."* The question of light and shade need really not have been entirely disregarded when drawing in outline alone. The lines might have been made stronger where the Ruskin.

FIG. 12. SIMPLE ARCHITECTURAL STUDY IN PROPORTION AND PERSPECTIVE.

The boundary of the shade occurred, and have tapered off to fineness where they approached the highest limits (see the scale of tones in Fig. 30) For practice in acquiring the power of doing this the drawing in outline of parts of the human form cannot be bettered. The play of light and shade upon the human form presents the most subtle curves in the shapes of gradated masses, and therefore offers exercises in the depiction of these by line which will test the most accomplished draughtsman. Fig. 10, by Mr. Ross Burnett, shows how successfully the human form can be drawn in line, and it is instructive to compare this with the meticulous technique employed in Lord Leighton's study of the hands in Fig. 3.

It is in the addition of light and shade, and the giving to the various passages of the drawing the correct relative tone value where the question of technique in lead pencil work becomes insistent.

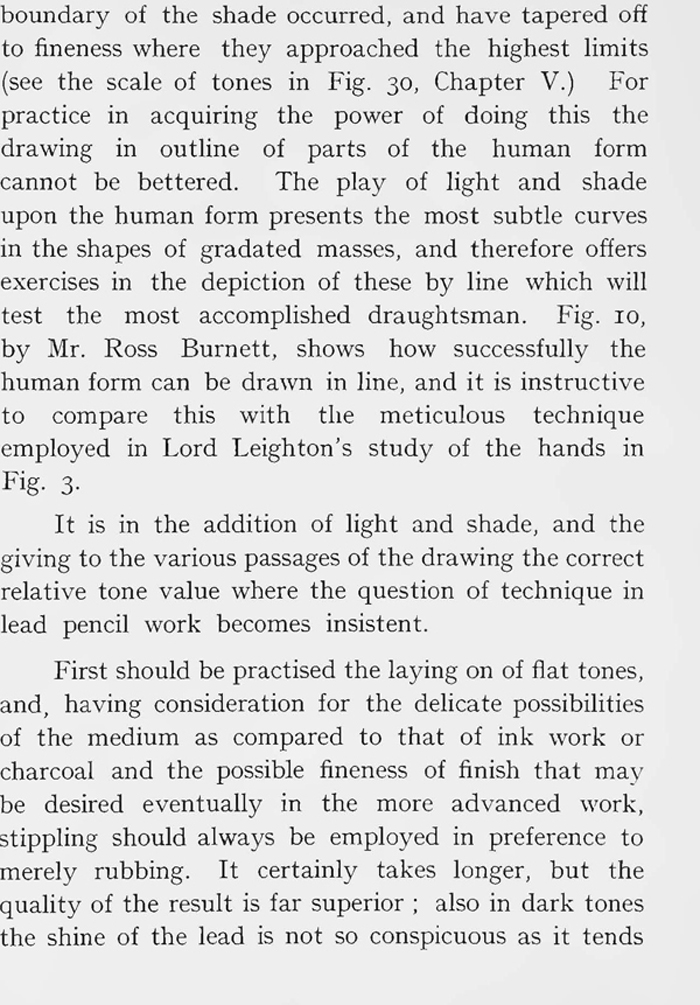

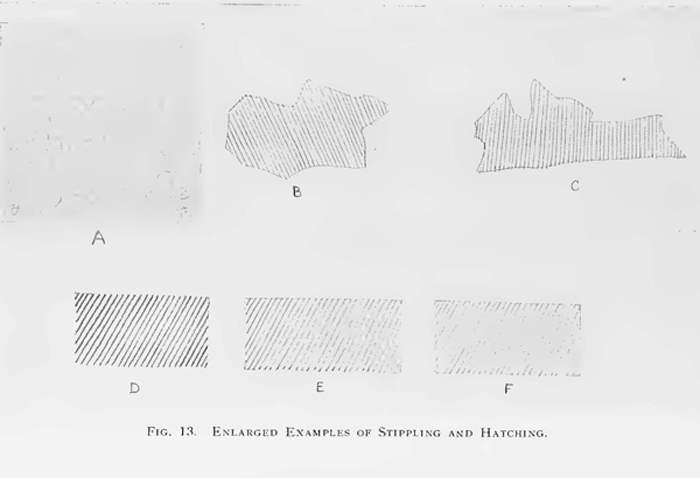

First should be practised the laying on of flat tones, and, having consideration for the delicate possibilities of the medium as compared to that of ink work or charcoal and the possible fineness of finish that may be desired eventually in the more advanced work, stippling should always be employed in preference to merely rubbing. It certainly takes longer, but the quality of the result is far superior ; also in dark tones the shine of the lead is not so conspicuous as it tends to be if the tone is rubbed on. Therefore when requiring to lay flat tones, especially the lighter tones, where evenness is particularly desirable, the pencil should be held in a rather more vertical position than for other purposes. The point should then be moved irregularly over the surface, but with care to maintain an even strength of tone. It might be better, perhaps, to describe the operation as a careful process of filling a specific area by means of a continuous interlacing line carried on until the particular depth of tone required has been produced.

Fig. 13 (a), a magnified reproduction of a tract of stippling, will explain the method described. An advantage of this method is that a tone obtained by stippling has more luminosity than one rubbed on. In the former case, if the stippling is not carried on too long, numerous minute patches of paper still uncovered remain which give the luminous appearance which is sometimes specially needed, for instance, in a back sky.

The third method of applying tones is, of course, that of hatching. For all general work where delineation and massing of tone values is inter-related, the principle of hatching, viz., of drawing lines parallel to each The term "back sky" as used here and in the various parts of the book is chosen to describe the blue of the outer sky, as differentiated from the clouds.

The other and very near together, is the technical method most proper to lead pencil drawing.

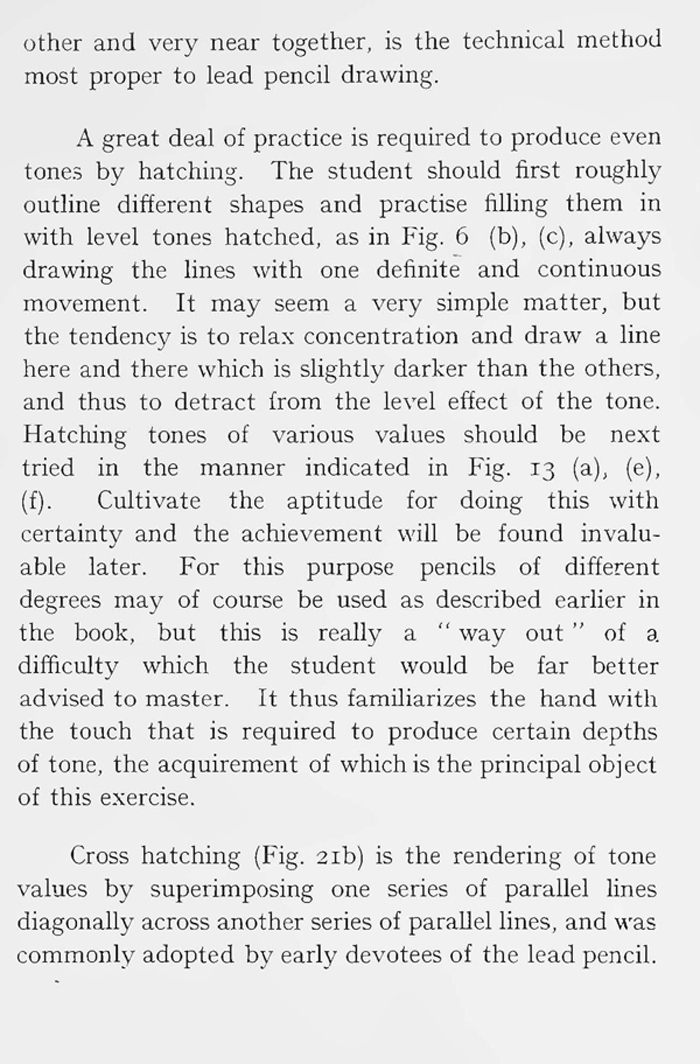

A great deal of practice is required to produce even tones by hatching. The student should first roughly outline different shapes and practise filling them in with level tones hatched, as in Fig. 6 (b), (c), always drawing the lines with one definite and continuous movement. It may seem a very simple matter, but the tendency is to relax concentration and draw a line here and there which is slightly darker than the others, and thus to detract from the level effect of the tone. Hatching tones of various values should be next tried in the manner indicated in Fig. i3 (a), (e), (f). Cultivate the aptitude for doing this with certainty and the achievement will be found invaluable later. For this purpose pencils of different degrees may of course be used as described earlier in the book, but this is really a " way out " of a difficulty which the student would be far better advised to master. It thus familiarizes the hand with the touch that is required to produce certain depths of tone, the acquirement of which is the principal object of this exercise.

Cross hatching (Fig. 21b) is the rendering of tone values by superimposing one series of parallel lines diagonally across another series of parallel lines, and was commonly adopted by early devotees of the lead pencil.

It is still sometimes employed, but the effect produced is rather mechanical, though it must be admitted that, as a corrective, it is a better way of darkening a hatched tone when the latter has not been drawn sufficiently strong than to go over the hatched lines a second time.

FIG. 14. GRADUATIONS IN TONE OBTAINED BY STIPPLING AND HATCHING.

A need that obviously follows after attaining proficiency in laying flat tones is that of practising gradation and modelling.

Spaces should be outlined—commencing with rectangular ones for preference—and tones graduating from darkness on one edge to lightness on the other should be laid first by stippling as in Fig. 14 (a), and then by lines as in Fig. 14 (b).

Fig. 14 (c) shows the application of these methods to elementary modelling, beginning in a simple manner and gradually treating more difficult shapes. The student will now begin to see for himself how the whole problem of complex work can be mastered by applying this technique as required. The wedge-shaped line or double-pointed line are both easily produced with the pencil and their application for various purposes and for producing various effects is a inore advanced matter which is described later on.

Before passing from the question of line, outline and elementary modelling, to the matter of technique in advanced work, it must not be forgotten by the student that, though line drawing is so particularly a convention, great work has been done in this manner alone without the addition of any light and shade. The work of J. D. Ingres particularly reveals the wonderful possibility of line drawing and the charm which a master can give to so simple a medium. But the pencil, possessing so many other possibilities besides that of mere delineation, and being concerned here, as we are, with all its potentialities, the student who desires to fully master the art must proceed to study the technical problems of juxtaposing different tones, the massing of lights and shades, the choosing of tone schemes, and the manner of producing the various effects necessary for the working out of his ideas ; also the complete rendering of drawings which, in comparison with sketches and even more advanced work, may claim to be deeply considered and highly finished.

The more advanced technique of pencil drawing requires the closest attention of the student if he is to grasp the full possibilities of the medium of lead pencil. When the artist has really mastered the art of using his pencil it is doubtful whether any other medium would provide greater interest or scope for the embodiment of beauty and truth. Outline, form, light and shade, tone, atmosphere, and even a sense of colour, all in infinite varieties of combination, may be depicted in so pleasing a manner as to give both constant and arresting delight.

The technical difficulties increase greatly as the student's work becomes more ambitious, and he sees more deeply into the beauties of Nature. Though it may lead to the artist being seldom completely satisfied with his own work, it is not likely to prove detrimental to creative effort, but rather to stimulate him to greater success. Such satisfaction is reached more often, perhaps, with ultra-impressionistic colour productions where the modern tendency is often to sacrifice beauty of form and composition in order to secure advertisement by eccentricities of individual technique, than with the more intellectual art of the pencil draughtsman. The student will seldom at first execute a drawing which is entirely harmonious and equal in regard to technique. With perseverance, however, he may soon come very near to doing so, for in pencil work the methods become obvious sooner than they do in colour, probably because the truthful arrangement of form and tone value, relieved of the added difficulty of colour, is more easily mastered.

In the course of his study the student will do well to carefully compare the works of the old masters with those of modern artists, paying special attention to their technique. For a hundred years or more after the Borrowdale lead mines were opened in the seventeenth century no lead pencil drawings of any importance are known to have been executed. About 183o the Art may be said to have come into fashion, when pencil drawing was substituted to some degree in early education for painting. Many of these early studies were executed in pencil with light washes of colour, or flicks of Chinese white added, a fashion which dates from 185o to 1875. Very many of these conscientiously executed and rather laborious drawings are still to be found preserved in museums, where praiseworthy studies of animals, rustic figures, branches of trees, leaves and flowers, are treasured, as forming a link in the history of art. These early drawings are highly contrasted to the work of the present day. The former lack the spirit, the vigour and the bold emancipation of modern work, but at the same time are remarkable for their delicacy and softness, and in regard to technique they set a high standard by their equality and painstaking labour ; the gradation in the modelling is usually quite wonderful, even when viewed through a magnifying glass.

Outlines of profiles of two or more heads depicted one against the other upon one sheet were popular. Fig. 16 is a characteristic example of this style. It is a good instance of the interest of pure outline, and is drawn with a confidence and precision which has evidently been carefully cultivated.

So far, however, I have not been able to discover any pencil drawing Qxecuted during the brief period of its popularity which evidences any attempt to realize the full potentialities of the medium, or to even make use of any very wide range of tone values in depicting landscapes, topographical subjects, etc. The several tones which were sometimes employed were used only to differentiate textures.

VIGNETTED SKETCHES OF COMMON OBJECTS.

The late nineteenth century lithographs which were until recently used as copies in schools are reproductions from original pencil drawings. They were drawn by Cattermole, Vere Foster, and others—and are quite bold and pleasing as far as they go, but they are usually mere vignetted sketches at most, bound by a conventional law of composition and effect from which they seldom depart. If followed too assiduously they are liable to detract from the freedom and largeness of outlook essential to more serious and ambitious pictorial art.

Every student should, however, give his attention to making a study of some of these examples, of which Fig. 17 is typical, because as exercises they will prove beneficial.

The advantage of mastering the method of vignetted studies is that it forms a sound training in the manner of obtaining equality of technique which will ultimately tend to raise the value of the student's more finished work. By beginning with these small studies and by aiming at making these pleasing in themselves, the student will more easily see where his technique tends to fail and thus be able to correct it accordingly. They also assist to cultivate simplicity and breadth, and provide training for the faculty of selecting essentials.