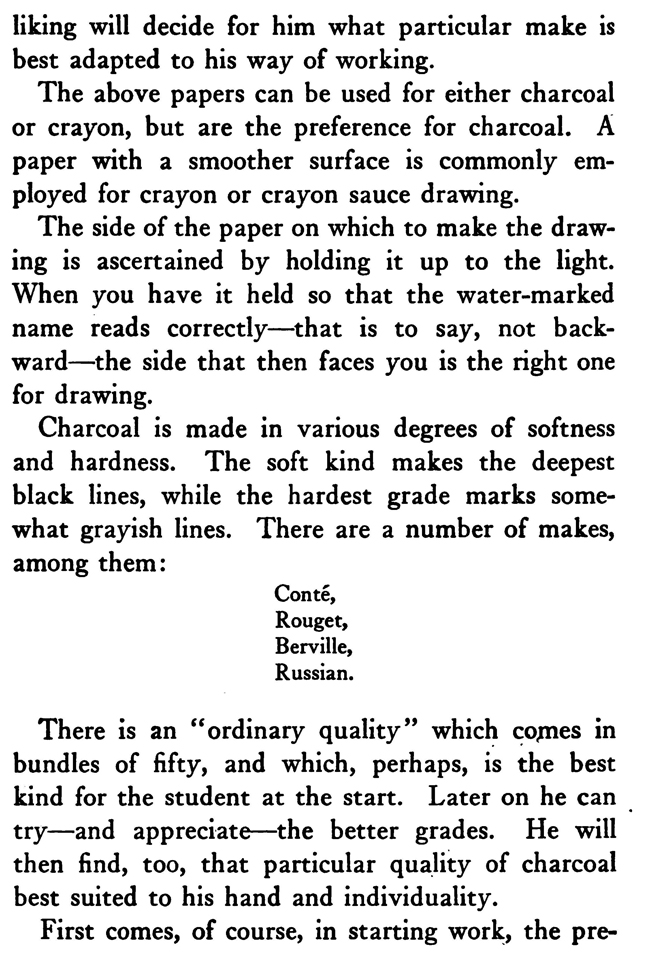

Working with charcoal, or fusain, on a special paper for the purpose, is the generally accepted method for the beginner in drawing when he gets down to serious study from casts or life. It holds its superiority as a medium for the student on account of the ease with which the materials can be managed. Conte crayon and crayon sauce are also enlisted in the service of art instruction. Their use is especially recommended in elementary work from casts.

Four of the principal makes of charcoal paper are as follows:

Lalanne, Michallet, Ingres, Allonge.

There are other kinds, too, all good. The beginner need not be too solicitous about which one he should use; when he becomes proficient in handling the charcoal and the few requisite tools, his artistic liking will decide for him what particular make is best adapted to his way of working.

The above papers can be used for either charcoal or crayon, but are the preference for charcoal. A paper with a smoother surface is commonly employed for crayon or crayon sauce drawing. The side of the paper on which to make the drawing is ascertained by holding it up to the light. When you have it held so that the water-marked name reads correctly—that is to say, not backward—the side that then faces you is the right one for drawing.

Charcoal is made in various degrees of softness and hardness. The soft kind makes the deepest black lines, while the hardest grade marks somewhat grayish lines. There are a number of makes, among them:

Conte, Rouget, Berville, Russian.

There is an "ordinary quality" which comes in bundles of fifty, and which, perhaps, is the best kind for the student at the start. Later on he can try—and appreciate—the better grades. He will then find, too, that particular quality of charcoal best suited to his hand and individuality.

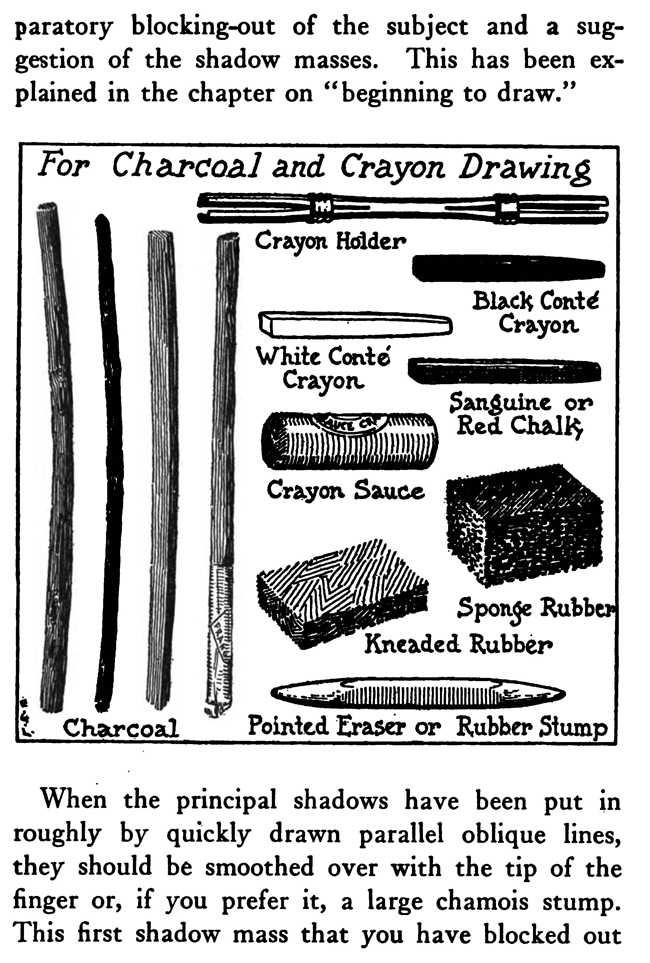

First comes, of course, in starting work, the preparatory blocking-out of the subject and a suggestion of the shadow masses. This has been explained in the chapter on "beginning to draw."

When the principal shadows have been put in roughly by quickly drawn parallel oblique lines, they should be smoothed over with the tip of the finger or, if you prefer it, a large chamois stump. This first shadow mass that you have blocked out and smoothed over should represent a degree of tint between the darkest and the lightest. That is, approximately the half-tint, or what you think the half-tint to be.

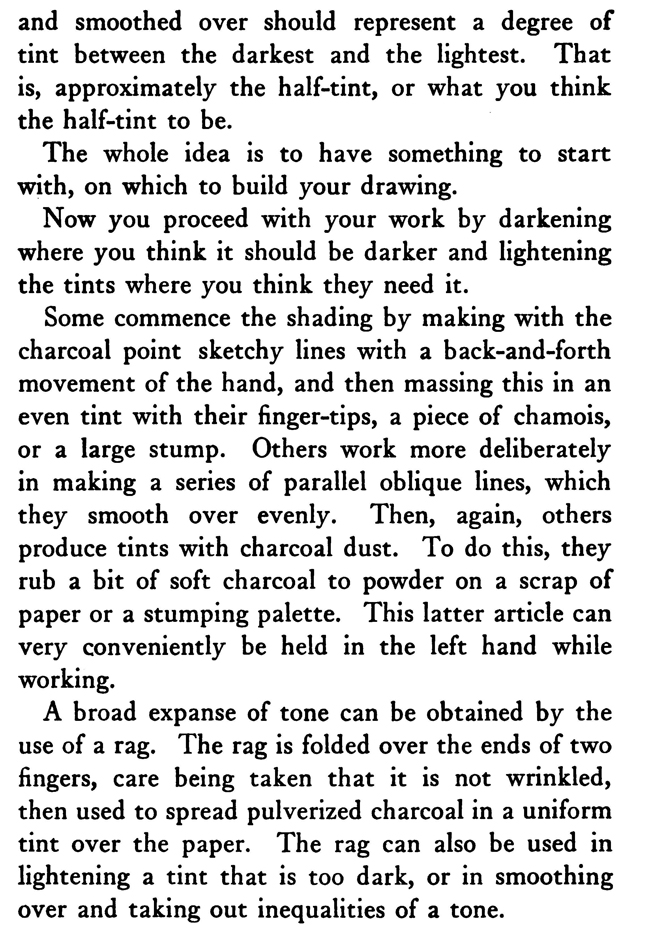

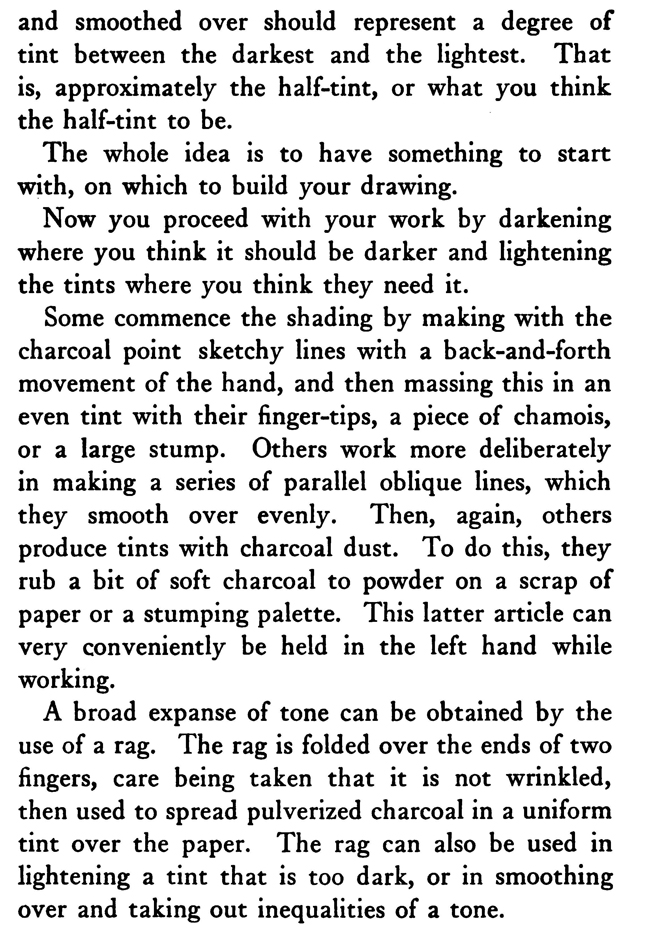

The whole idea is to have something to start with, on which to build your drawing. Now you proceed with your work by darkening where you think it should be darker and lightening the tints where you think they need it. Some commence the shading by making with the charcoal point sketchy lines with a back-and-forth movement of the hand, and then massing this in an even tint with their finger-tips, a piece of chamois, or a large stump. Others work more deliberately in making a series of parallel oblique lines, which they smooth over evenly. Then, again, others produce tints with charcoal dust. To do this, they rub a bit of soft charcoal to powder on a scrap of paper or a stumping palette. This latter article can very conveniently be held in the left hand while working.

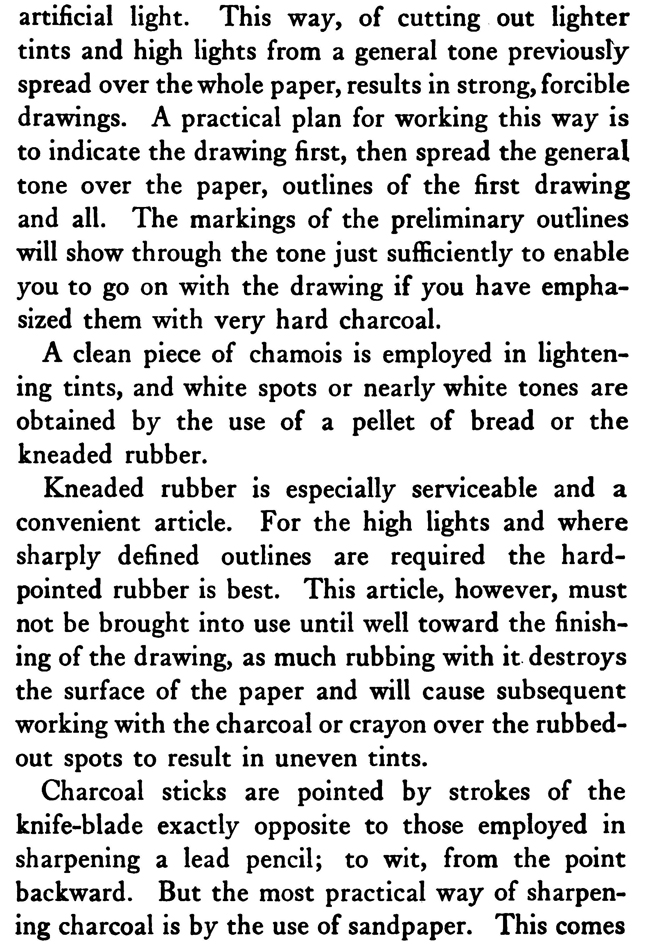

A broad expanse of tone can be obtained by the use of a rag. The rag is folded over the ends of two fingers, care being taken that it is not wrinkled, then used to spread pulverized charcoal in a uniform tint over the paper. The rag can also be used in lightening a tint that is too dark, or in smoothing over and taking out inequalities of a tone. Another method is to cover the whole surface of the paper with an even shade of charcoal, then going on with the drawing, putting in darker tints and taking out any lighter ones with a piece of chamois or kneaded rubber. Some become very skilful in this method and handle the materials with great facility. It is a good way to work where the subject or model is under a strong effect of artificial light. This way, of cutting out lighter tints and high lights from a general tone previously spread over the whole paper, results in strong, forcible drawings. A practical plan for working this way is to indicate the drawing first, then spread the general tone over the paper, outlines of the first drawing and all. The markings of the preliminary outlines will show through the tone just sufficiently to enable you to go on with the drawing if you have emphasized them with very hard charcoal.

A clean piece of chamois is employed in lightening tints, and white spots or nearly white tones are obtained by the use of a pellet of bread or the kneaded rubber. Kneaded rubber is especially serviceable and a convenient article. For the high lights and where sharply defined outlines are required the hard-pointed rubber is best. This article, however, must not be brought into use until well toward the finishing of the drawing, as much rubbing with it destroys the surface of the paper and will cause subsequent working with the charcoal or crayon over the rubbed-out spots to result in uneven tints.

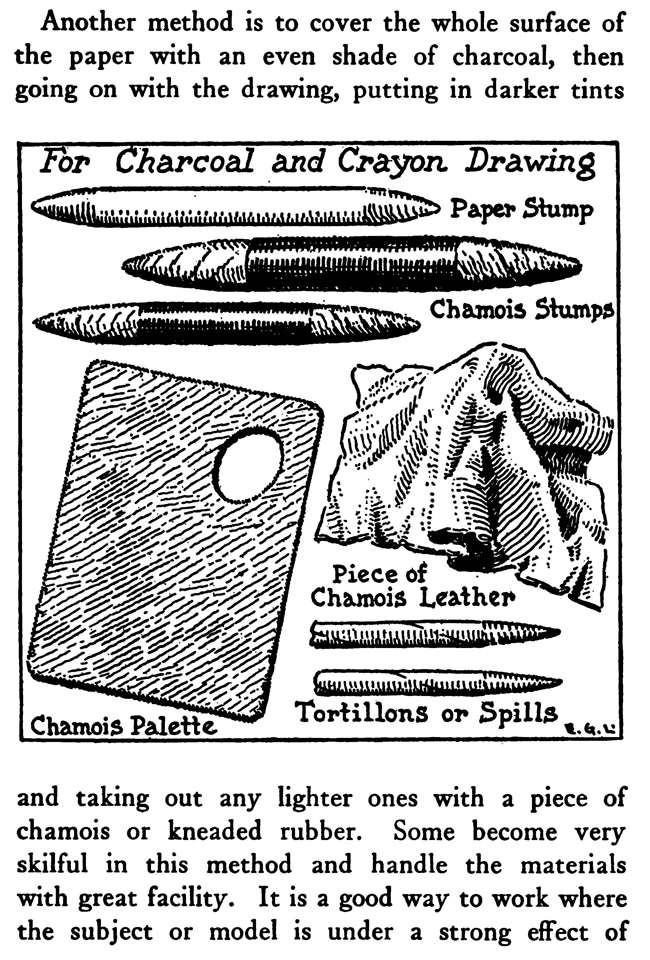

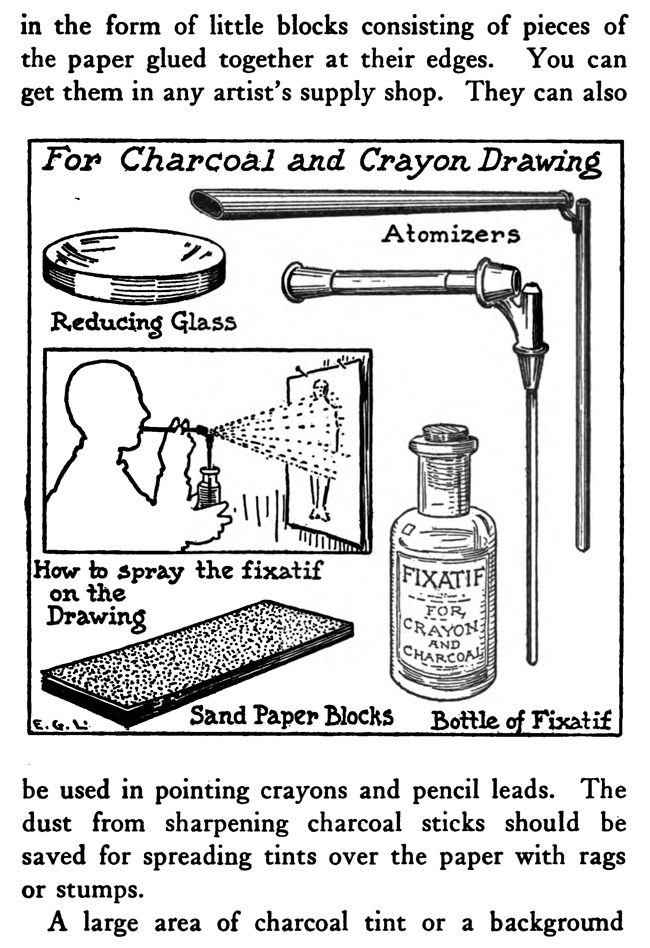

Charcoal sticks are pointed by strokes of the knife-blade exactly opposite to those employed in sharpening a lead pencil; to wit, from the point backward. But the most practical way of sharpening charcoal is by the use of sandpaper. This comes in the form of little blocks consisting of pieces of the paper glued together at their edges. You can get them in any artist's supply shop. They can also be used in pointing crayons and pencil leads. The dust from sharpening charcoal sticks should be saved for spreading tints over the paper with rags or stumps.

A large area of charcoal tint or a background Sand Paper Blocks Bottle. of Fixat if that is too dark can be lightened a little by the use of a sponge rubber. The soiled margins of the paper can also be cleaned with this rubber. The water-mark lines in certain kinds of charcoal paper, which are sometimes very evident in finished work, are not considered detrimental to a drawing. For the crayon, especially when studying from casts, a special crayon paper is preferable. This paper has not that roughness of surface characteristic of the charcoal papers; but is grained uniformly and gives smooth, unbroken tones that render successfully the transparency of the shadows in a plaster cast.

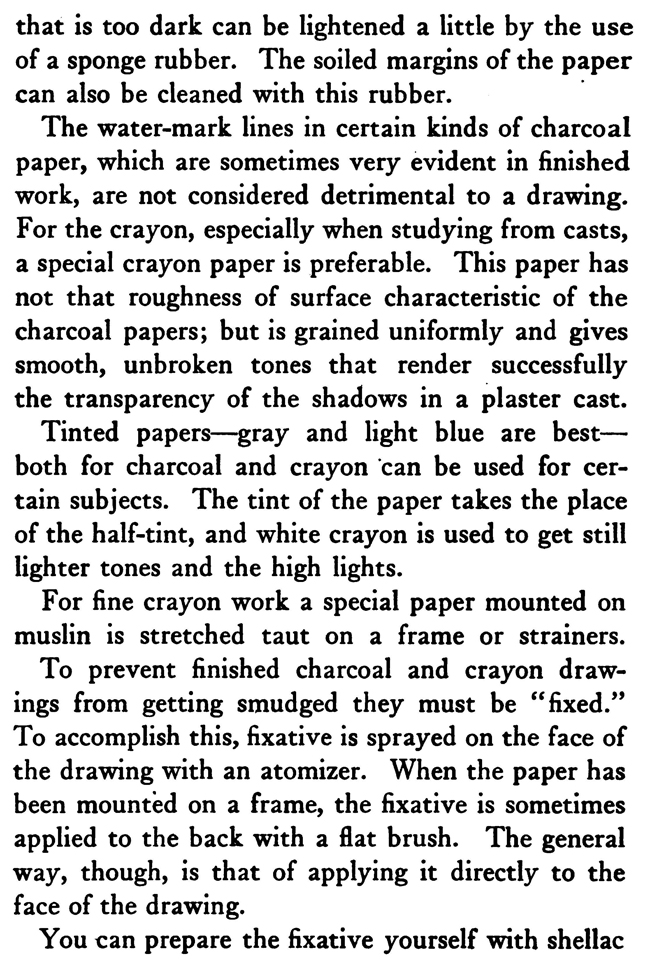

Tinted papers—gray and light blue are best—both for charcoal and crayon can be used for certain subjects. The tint of the paper takes the place of the half-tint, and white crayon is used to get still lighter tones and the high lights For fine crayon work a special paper mounted on muslin is stretched taut on a frame or strainers. To prevent finished charcoal and crayon drawings from getting smudged they must be "fixed." To accomplish this, fixative is sprayed on the face of the drawing with an atomizer. When the paper has been mounted on a frame, the fixative is sometimes applied to the back with a flat brush. The general way, though, is that of applying it directly to the face of the drawing.

You can prepare the fixative yourself with shellac and pure alcohol; but care must be taken not to get the mixture of a yellowish tinge, or it will discolor the drawing, To obviate any such occurrence you had better get it all prepared from the shop. Most of the atomizers are made with the two parts of which they are constructed hinged. It is necessary when using one always to hold the two parts bent at the correct angle. But you can get kinds made with the tubes fixed at the required angle.

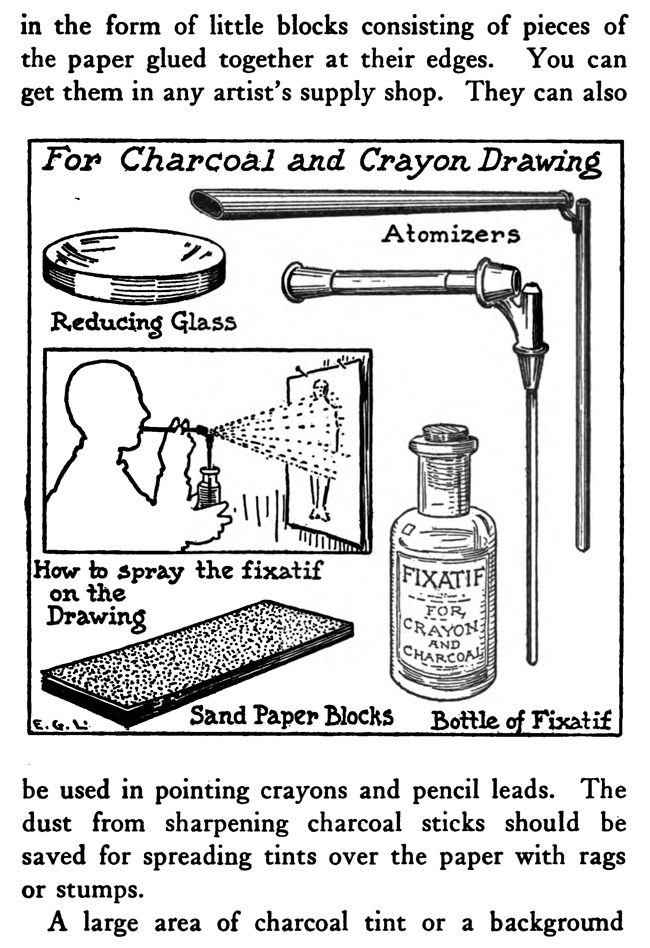

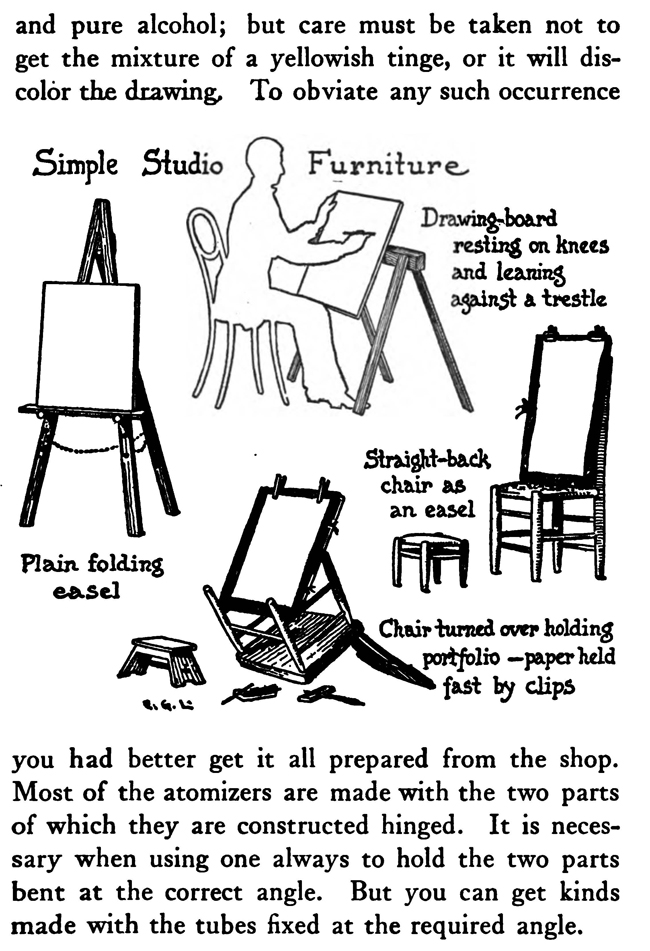

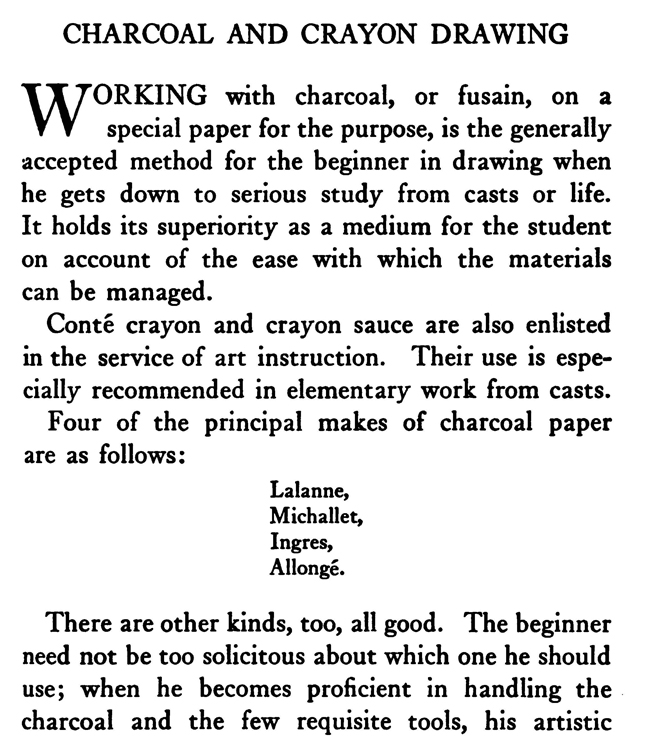

Drawing-board resting on knees and leanins asainst a trestle Chair turned over holding portfolio —paper held fast by clips

To use the atomizer: Place the small tube into the bottle of the fixative and blow into the other—the one with the mouthpiece.

Now, if you have blown with just the right amount of force and the tubes have been held at the proper angle, one to the other, the result will be a fine spray of the vaporized liquid. You must be careful in placing yourself at the correct distance from the drawing, which has been previously pinned to hang vertically on the wall or an upright board. If you get too close to the drawing, instead of a fine vapor, drops of fixative will gather and run down the surface of the paper. Just one little splotch with a track of the trickling liquid will, of course, ruin your drawing. This can be easily avoided by first getting the right distance by trying the operation on the board alongside of the drawing. Be sure to clean out the atomizer after using, as any fixative left in the small tube, in drying, will cause it to become clogged. To prevent this blow water through it immediately after using.

Drawings for reproduction by the photo-engraving processes can be made with charcoal or crayon. If they are intended for the ordinary line or zinc engraving they must not be rubbed over. It is important to remember this. The lines or markings are not to be smoothed over with the chamois or stumps, as the depressions in the roughly grained paper must show a clear white. Exactly as in pen-and-ink, the requirements are that black marks and lines be of an intense black and not of a grayish appearance.

For the half-tone process you need not trouble about the blackness of the markings, but see to it that you produce, with all the artistic skill at your command, a drawing distinguished by good and artistic contrasts. Often a drawing started with charcoal, if washed in with monochrome, results in an effective composition, giving a soft blending of shades and pleasing contrasting tones.

Charcoal.

Black crayon.

Crayon sauce, or velours a sauce. Comes in vials or wrapped in foil.

Paper, charcoal and crayon.

Crayon holders, or porte-crayons.

Rags, to spread tints over large areas.

Chamois leather.

Stumps, of chamois, large paper ones, and of cork. To smooth tints, and carry crayon sauce from the chamois palette to the drawing.

Tortillons, or spills.

Small paper stumps for detail, etc. They come in bundles of fifty

Kneaded rubber, an indispensable article for making changes, lightening tints, etc. It can be pushed into a point and used to sharpen outlines or details. It has practically taken the place of bread which was formerly used in charcoal work.

Pointed eraser, or rubber stump to take out high lights.

Chamois palette, to hold the crayon sauce.

Reducing glass or lens. One about two inches in diameter. Examine your drawing with it from time to time. Values not in keeping show out very conspicuously when viewed through it.

White Conte crayon, for high lights when tinted paper is used. In working on white paper learn so to manage your material that the white paper will represent the high lights.

Sponge rubber.

Lithographic, or wax crayon, to get a jet black. But remember it cannot be erased.

Fixative. An excellent quality comes prepared. But if you wish to make it yourself, dissolve dry white shellac in pure alcohol.

Atomizers.

Sanguine, or red chalk. Makes very effective sketches, especially if the lines are not smoothed over into tints.

Blocks of sandpaper to sharpen the charcoal or crayons. Easels.

Portfolio. One 20 by 26 inches is the exact size for holding the sheets of charcoal paper. Instead of a board, a portfolio of this size will answer. The paper is fastened at the top by wooden or metal spring clips.