DRAWING TREES

TREES

NOTHING in landscape causes so much trouble to the beginner (and to many others) as trees. A cottage, with its

comparatively simple and straightforward arrangement of plane surfaces, is soon mastered ; but the multiplicity of leaves and stems are often bewildering in their complexity. There is no gainsaying the fact that the drawing of trees is not easy. They have to be studied, and the only question is the most simple and systematic means.

Obviously trees cannot be drawn exactly as they appear. We can see millions of leaves, but we cannot make enough spots ! We can only suggest and leave the spectator to fill in the details (if he wants to) from his experience of real trees. We can best do this by indicating its salient characteristics—its differences from other kinds of trees. We cannot draw a tree but we can suggest its ' tree-iness.' The barest note of a dozen lines of, say, an elm, must not be mistaken for a willow. The things we can do —the proportions, general shape, masses, arrangement of stems—are our chief concerns. Often it is necessary to emphasize what we can do in order to suggest what we cannot do.

Let us take the elm and the willow and study them in this way (1) because they are found nearly everywhere, (2) they are rich in pictorial possibilities, (3) they are representatives of the

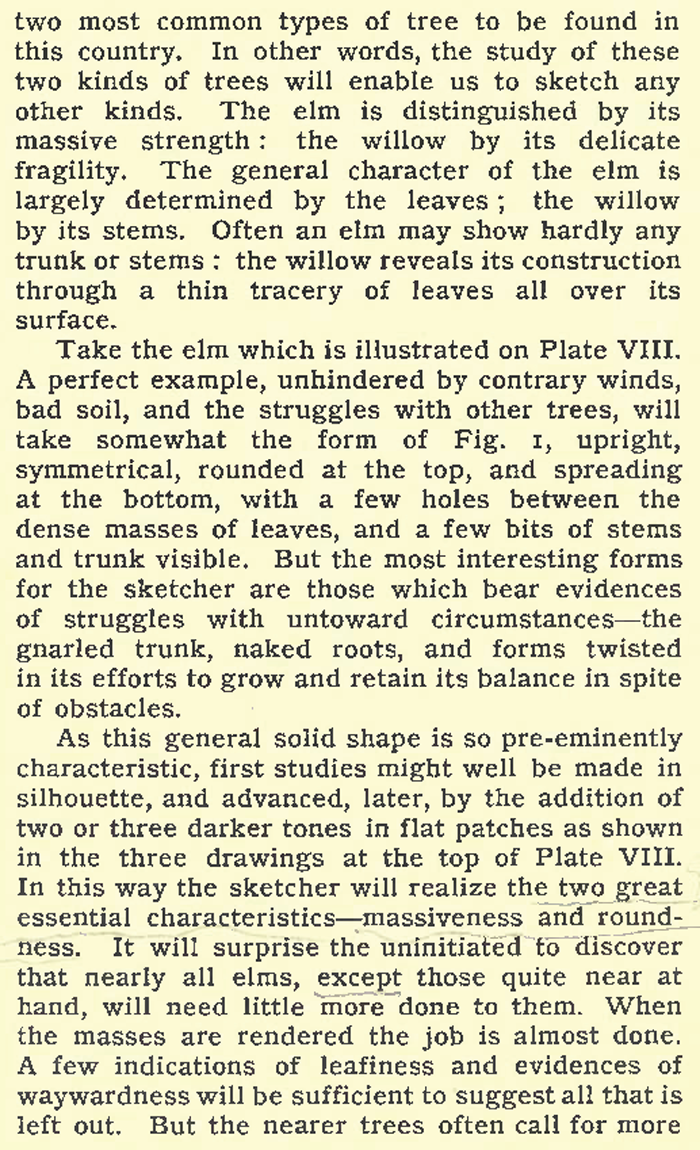

two most common types of tree to be found in this country. In other words, the study of these two kinds of trees will enable us to sketch any other kinds. The elm is distinguished by its massive strength : the willow by its delicate fragility. The general character of the elm is largely determined by the leaves ; the willow by its stems. Often an elm may show hardly any trunk or stems : the willow reveals its construction through a thin tracery of leaves all over its surface.

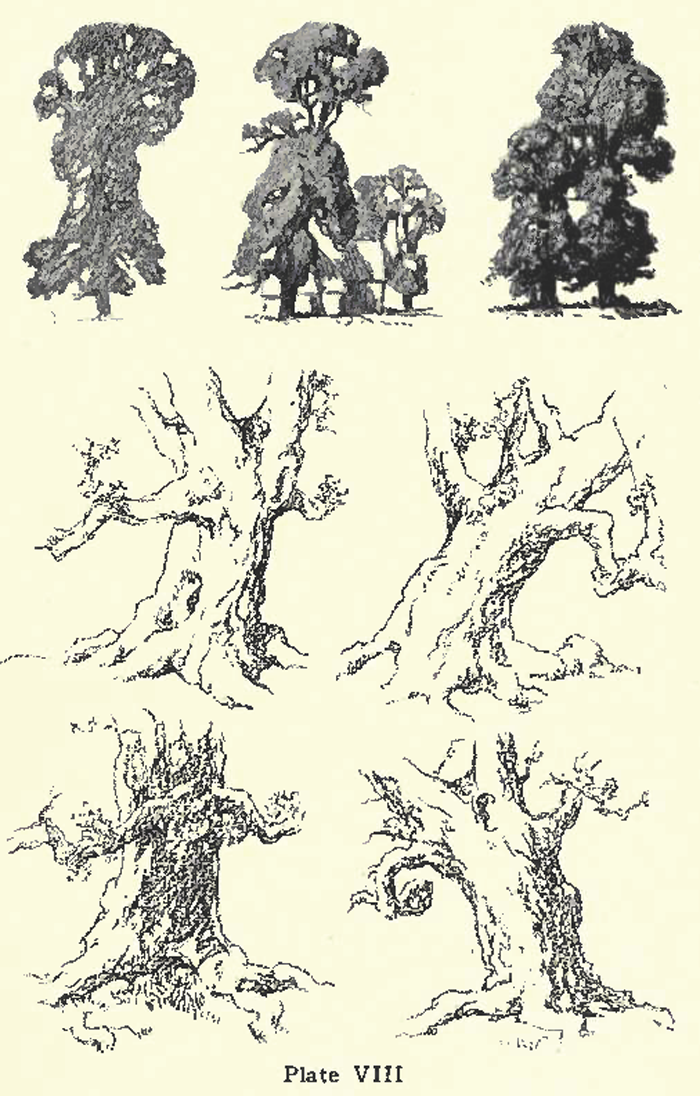

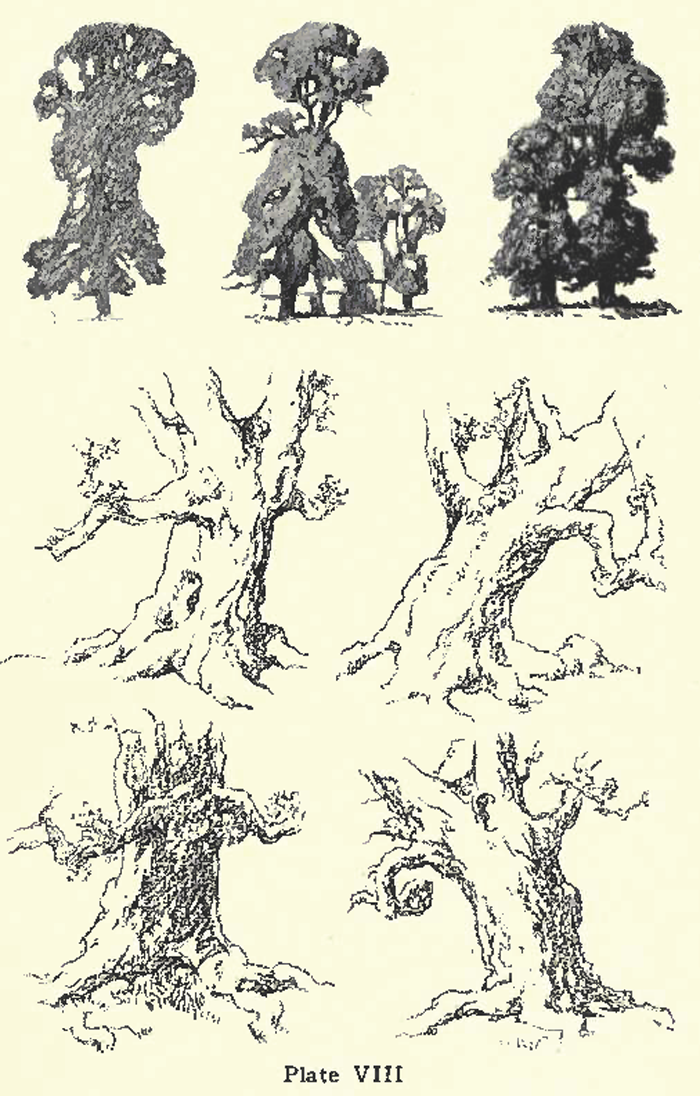

Take the elm which is illustrated on Plate VIII. A perfect example, unhindered by contrary winds, bad soil, and the struggles with other trees, will take somewhat the form of Fig. 1, upright, symmetrical, rounded at the top, and spreading at the bottom, with a few holes between the dense masses of leaves, and a few bits of stems and trunk visible. But the most interesting forms for the sketcher are those which bear evidences of struggles with untoward circumstances—the gnarled trunk, naked roots, and forms twisted in its efforts to grow and retain its balance in spite of obstacles.

As this general solid shape is so pre-eminently characteristic, first studies might well be made in silhouette, and advanced, later, by the addition of two or three darker tones in flat patches as shown in the three drawings at the top of Plate VIII. In this way the sketcher will realize the two great essential characteristics—massiveness and roundness. It will surprise the uninitiated-to dikover that nearly all elms, except those quite near at hand, will need little more done to them. When the masses are rendered the job is almost done. A few indications of leafiness and evidences of waywardness will be sufficient to suggest all that is left out. But the nearer trees often call for more

(

Plate x"

Univ Calif - Digitized by Microsoft

Univ Calif - Digitized by Microsoft

Plate XIII

detailed representation. The other sketches on Plate VIII show four sketches of the trunk of an old elm, drawn from different points of view, with a soft pencil on very coarse paper. This is one of the simplest ways to express the essential character of weather-beaten age in a few strokes.

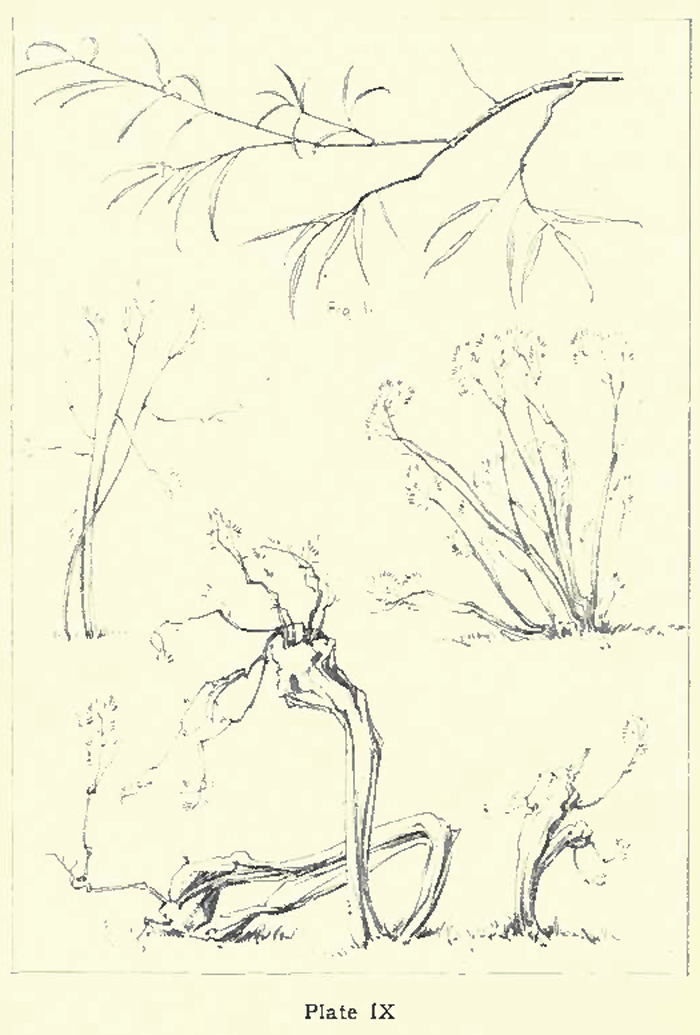

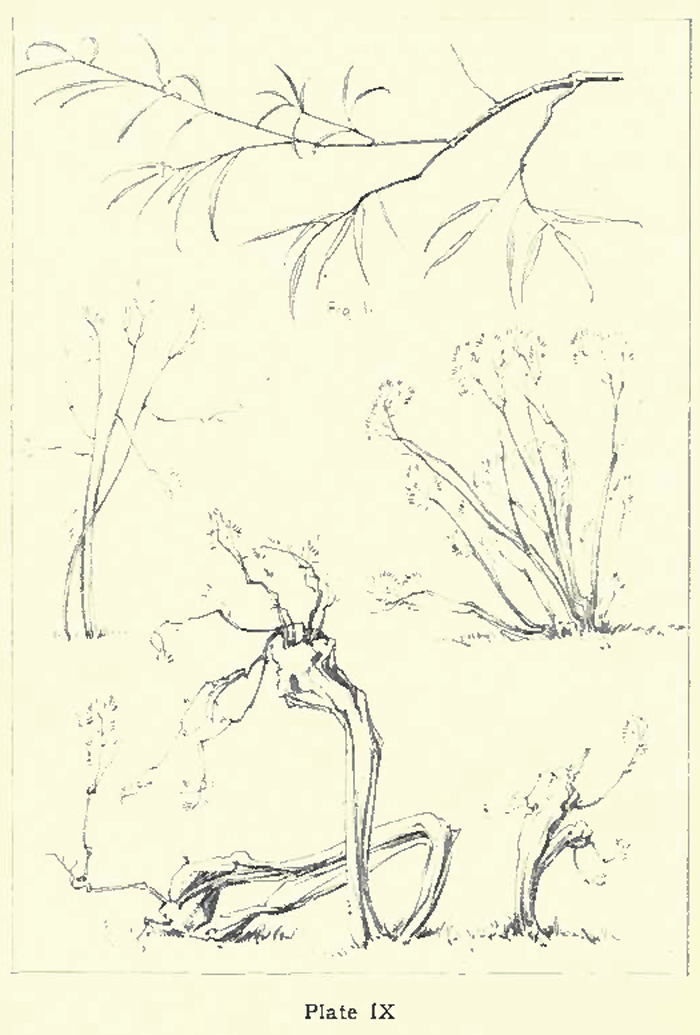

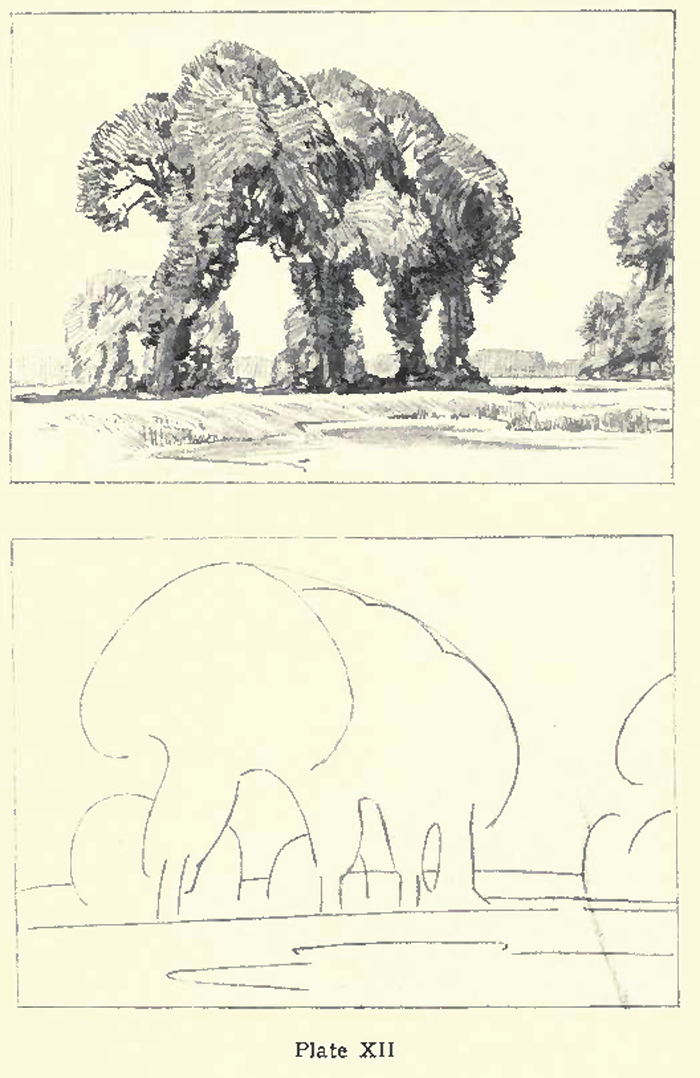

Now for the willow. Plate IX consists of studies of the willow showing its totally different qualities. There are several kinds of willows. Some, at a distance, might almost be mistaken for poplars, and others for ash trees ; but the sketcher will be drawn to the more distinctive varieties. Here the stems are the crux of the problem. By far the most thorough method of study is to first draw the tree when the stems are bare, then when the shoots appear, and later when in full leaf.

Unlike the dominating elms the willow is greatly influenced by circumstances ; usually it is beaten in the struggle for free growth. It turns and twists and falls in almost every imaginable direction. For this reason alone it appeals to the artist who can do with it what almost he will without violating any natural law.

In this tree a knowledge of the way the leaves grow is unusually important. A few studies such as Fig. i will show why the edges of the trees look soft, pale, and indeterminate.

The other illustrations in this plate point to another important fact, viz. : that the willow admits of great latitude in composition. Stems can be drawn in almost any direction desired, but for the most part the drawing has to be in lines except on the old trunks, where powerful flat tones can often be used with great effect.

After drawing a dozen or so well-selected varieties of each tree in several positions, the sketcher should have acquired the power to be

able to modify the form at will without violating its essential character. He should then proceed to combine some of these elements with some of his former studies into pictorial arrangements. The available material is now ample for serious practical experiments in composition. The dark masses of elms will produce powerful contrasts when combined with white cottages, and give opportunities for trying several technical methods. The willows, with their delicate upright or spreading trunks, will, by a less powerful but equally interesting contrast, give life and movement to flat and heavy masses. Water, the natural accompaniment of willows, can be introduced with quietly telling effect.

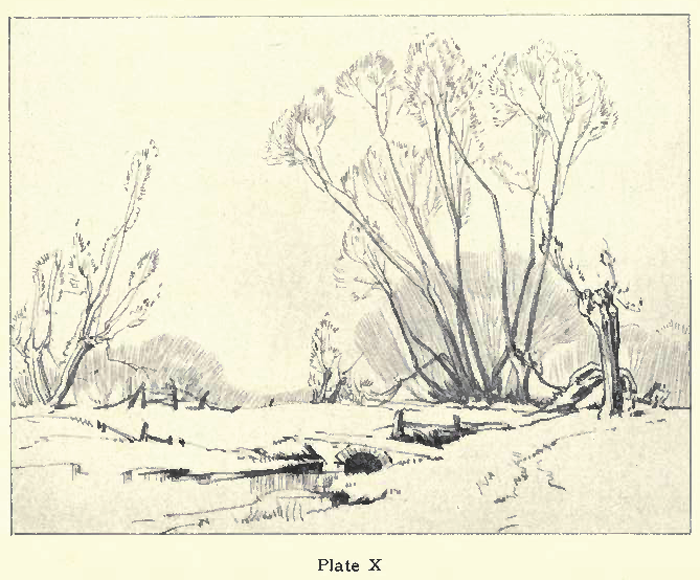

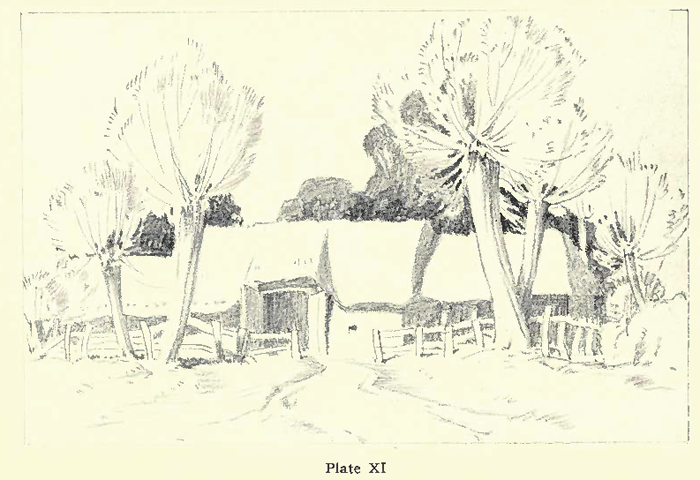

Plate X is a picture consisting mainly of details, shown on Plate IX, varied to suit the needs of the composition. Three pencils were used : 4H for the distance, HB for the middle distance, and 4B for the foreground. Plate XI shows an arrangement consisting of willows with a background of elms. This drawing was done entirely with a 3B pencil and varying pressure. In each case the conscious aim has been restricted to two effects (1) strong contrasts of dark against light, and curved masses and straight surfaces, (2) striking variety by the opposition of horizontal lines with those that are more nearly vertical.

However eager the sketcher may be to continue with studies of other features from nature, he will be well advised to consolidate the present position by making the most he is able of the material already collected. He will then begin to see how he can make rearrangements on the spot. The failure to apply newly gained knowledge at suitable intervals is one of the chief causes why so many sketchers never emerge from the preparatory stage of picture making.