Home > Directory Home > Drawing Lessons > How to Draw People > Drawing Figues by Memorizing Their Proportions

DRAWING FIGURES BY MEMORIZING THE HUMAN ANATOMY : Learn the Correct Proportions and Ratios of The Human Body

|

GO BACK TO THE HOME PAGE FOR CARICATURE DRAWING TUTORIALS

[The above words are pictures of text, below is the actual text if you need to copy a paragraph or two]

DRAWING HUMAN FIGURES WITH MEMORY DRAWING

To draw from memory, or to " chic " as the French have it, is an important requirement of the modern comic artist. For he must not only be able to draw figures very rapidly and often crowded together in a large composition, but to put these figures in such absurd and impossible attitudes that living models as a guide would be out of the question.

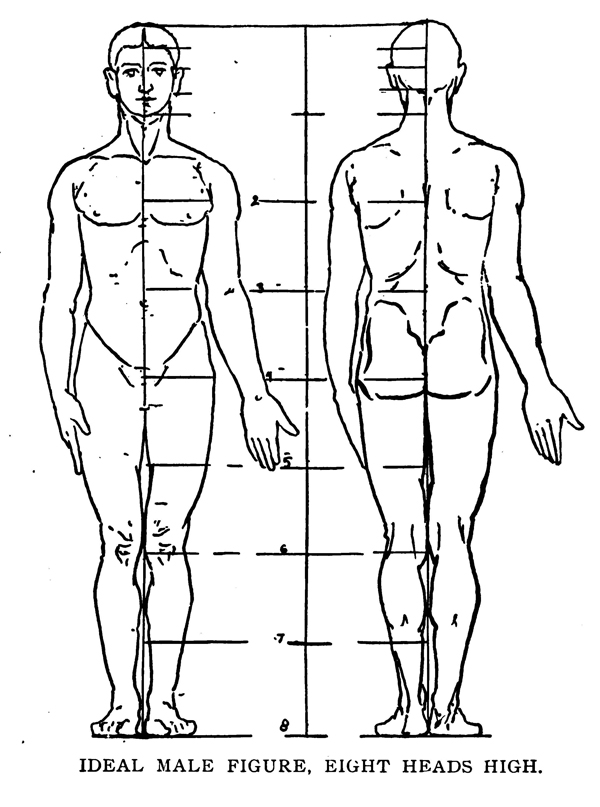

Artistic anatomy plays an important part in all memory drawing of the figure—so important, indeed, that it has been thought necessary to incorporate it in a separate chapter in this work.A cartoonist customarily sits down to a drawing board upon which is placed a blank drawing surface which he must cover with a convincing picture in an almost incredibly rapid time, with little or no data to work from except those furnished by an exceedingly active imagination and a well-stored mind. To memorize the ideal measurements and proportions of the male and female human figure should be the student's earnest endeavor, and, with this end in view, the essentials of the various tables that have been constructed for this purpose are presented here. The ideal male figure is eight heads high, which means eight skulls—the dimensions being based on the length of the skull without its covering of hair.

From the top of the skull, therefore, to the chin may be considered as one skull, the unit of measurement by this system. From the chin to the top of the breastbone is one-half a head and the length of the breastbone has a like measurement. From thence to just above the navel is one head; thence to the commencement of the lower limbs one head; thence to the middle of the thigh one head; thence to the bottom of the knee one head; thence to the small of the ankle one and one-half. beads; thence to the sole of the foot half a head.

When the arms hang limply at the side, with the fingers fully extended, they reach to the center of the thigh. Extending the arms at right angles forms a line, from finger tips to finger tips, equal to the length of the figure. The neck is half a head wide, the shoulders two heads wide, under the armpits one and one-half heads wide, across the waist one head and a quarter wide, the top of the thigh three-quarters of a head wide, the knee half a head wide. The calf is two noses and a half across, the ankle one nose across. The hand is three-quarters of the head in length. The foot, according to the ancients, is one-sixth of the length of the figure.

Tall and short men vary in proportion according to their height. As a rule, the divisions of the male figure hold good in the female figure as to length, though the widths of the various parts differ greatly. The neck is half a head wide, the shoulders one head and a half wide, the waist one head and one-eighth wide, across the hips two heads wide, the middle of the thigh three- quarters of a head wide. Across the top of the knee is two noses and a quarter, across the bottom of the knee half a face, across the calf two noses and a quarter, across the smallest part of the ankle one nose; across the instep, in its thickest part, is one-third of its length.

Most modern feet are so distorted by the shoe-wearing habit that they have lost much of their natural shape and action. Peoples who wear no shoes can, as a rule, use the feet with something of the facility of the hands. Feet have much the same construction as hands and for this reason can, when unhampered by artificial means, take their place to a great extent.

Generally speaking, women are not so tall as men, their necks being a trifle longer and set further back on the trunk. Their muscular development does not show so plainly through the skin as that of men. The general contour of their bodies is, therefore, more flowing and graceful.

The brain of an infant is larger in proportion than the brain of an adult, and the covering of fat on the body, limbs, and cheeks is very marked.

In aged persons the body becomes angular and the pleasing lines of youth disappear. To the artist, however, old age has its peculiar charm—every period of life, indeed, is pictorially interesting. Each age suggests to the imagination certain ideas, and the caricaturist should duly appreciate and make .use of this fact.

In infants the middle of the figure is situated at the navel. Children of three years average five heads in height, three of which may be allowed for the upper part of the figure. Children of six years are usually six heads high, their arms and legs be- coming noticeably thinner at this period. A youth of sixteen is about seven heads high, and at this age the figure divides itself, for the first time, into two equal proportions : one for the body and one for the lower limbs.

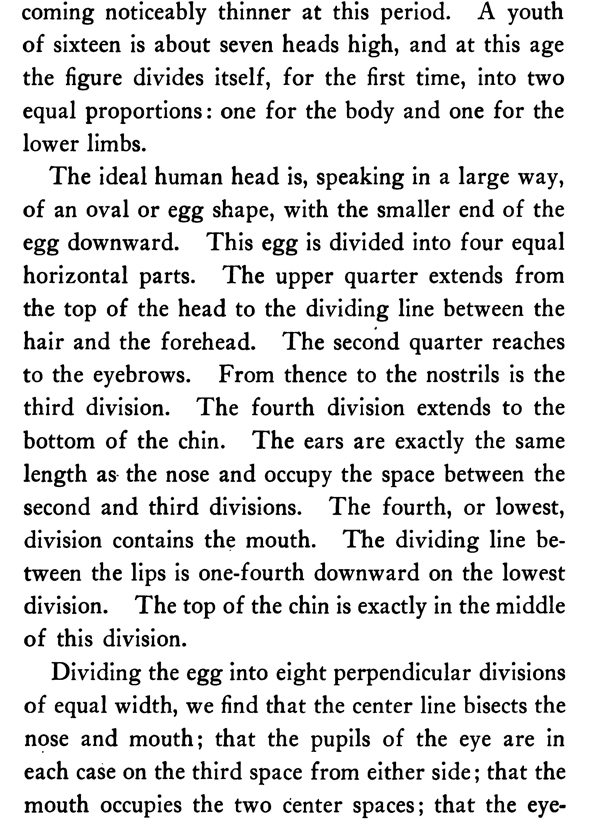

SHOWING THE HUMAN HEAD SUBDIVIDED IN SUCH A MANNER AS TO BE EASILY COMPREHENDED

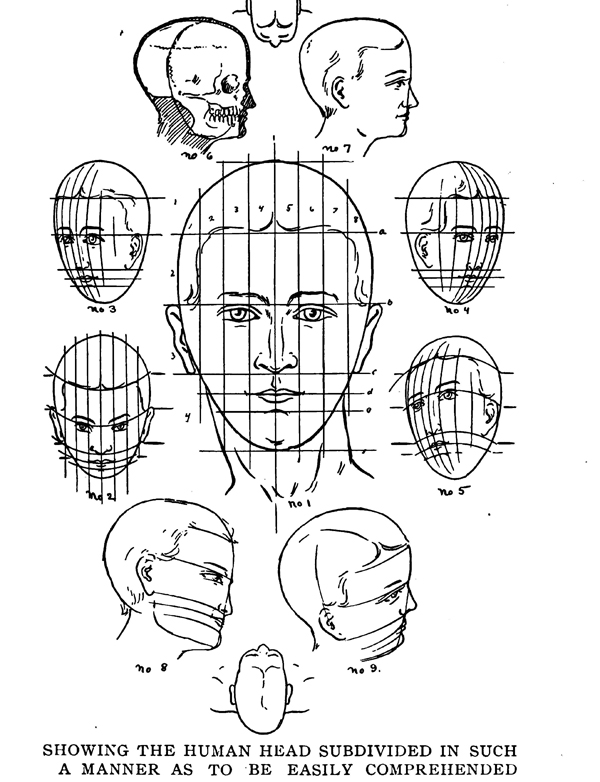

The ideal human head is, speaking in a large way, of an oval or egg shape, with the smaller end of the egg downward. This egg is divided into four equal horizontal parts. The upper quarter extends from the top of the head to the dividing line between the hair and the forehead. The second quarter reaches to the eyebrows. From thence to the nostrils is the third division. The fourth division extends to the bottom of the chin. The ears are exactly the same length as- the nose and occupy the space between the second and third divisions. The fourth, or lowest, division contains the mouth. The dividing line between the lips is one-fourth downward on the lowest division. The top of the chin is exactly in the middle of this division.

Dividing the egg into eight perpendicular divisions of equal width, we find that the center line bisects the nose and mouth; that the pupils of the eye are in each case on the third space from either side; that the mouth occupies the two center spaces; that the eyebrows commence at the second space from either side and extend to the middle of each of the two center spaces. It will be excellent practice, and will serve to impress the above truths on the mind, to take an egg and draw the divisions upon it with pencil, placing an outline of the features in the proper places. By holding the egg at different angles, the eye will instinctively grasp and the brain readily comprehend the effect of the natural subdivision of the human head when seen in the perspective, or foreshortened, as it is termed. The diagrams given here serve to bring out this idea quite clearly. Of course, when one looks at an exact side view of a head thus sketched upon an egg, the profile will be missing, and, owing to the lengthening of the skull at the back, the egg form must be varied from and added to, to produce the effect of reality. The horizontal divisions, however, hold good for the side view.

By tipping the egg slightly toward the eye or away from it it will be noticed that the foreshortening is somewhat increased, and in order to approximate nature, a drawing made from it would have to take into account the changed appearance of the features owing to the different point of view. For instance, when the top of a side-view head is tipped slightly away from the eye, more of the upper lip than the lower will be seen; one can look into the nostrils, under the lid of the eye, and under the arch of the eyebrow. On the other hand, in the same view with the top of the head tipped slightly toward the eye, less of the upper lip than the lower will be observed, the opening of the nostrils will not be seen, and the pupil of the eye will be partially hidden by the lid above it.

By a reasonable amount of practice, as outlined above, the construction of the ideal human head can be so firmly fixed in the mind that it will be found a comparatively easy matter to produce variations from the standard met with in everyday life. Thus, the cartoonist's typical Yankee face has these standard measurements as a basis, but is thinner and lanker. The average comic artist's conception of a German face is to change this ideal form by making it broader and adding such facial gardening in the way of whiskers as his fancy may suggest.

THE IDEAL EYE, EAR, NOSE AND MOUTH.

For ages the standards of beauty of face and form established by the Greeks have been recognized as correct. The artist who draws from memory should familiarize himself with these standards, for he must have some standard of comparison, no matter how grotesque the effect he aims for.It is of course unnecessary to dwell upon the fact that no rule, however well made, will cover the endless national and individual characteristics of the human form that one may observe, either in pictures or in life; but by continued reference to an ideal it will be found easier to draw a human figure of any proportions, whether it be a giant of Patagonia or a pygmy of Africa.

A sense of the facial peculiarities of each nation or race is always determined by the ideal which every person instinctively carries in his mind. It requires more careful observation, or a nicer power of discernment, to determine the differences in individuals of a - nation or family; but even these often subtle variations are readily grasped by the alert mind and what has been called the " prehensile eye " of the trained artist.

The only way to properly memorize the form of an object is to reproduce it by drawing or modeling until its contour and construction are firmly fixed in the mind.

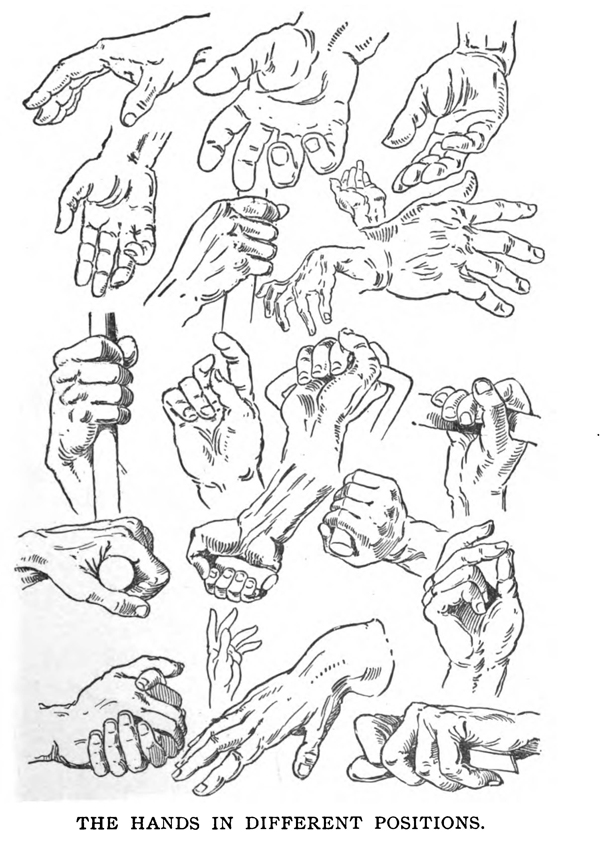

THE HANDS IN DIFFERENT POSITIONS.

The action or general movements of the body must always be grasped before a realistic memory drawing can be made. The simplest way to understand the action is to reduce it to the movements of the skeleton, and for the purpose of study one may still further simplify matters by reducing the skeleton to a few simple strokes which suggest it. To place five dots on a piece of paper in any imaginable combination, and to draw a skeletonized figure to conform to the five dots (letting each extremity touch one dot), will be found excellent practice.

Privacy Policy .... Contact Us