Home > Directory of Drawing Lessons > How to Improve Your Drawings > Drawing Confident Lines > Line Drawing Lessons

Line Art Drawing Lessons & Tutorials : How to Draw Pen Lines & Strokes with Variations of Thickness & Widths with Confidence

|

|

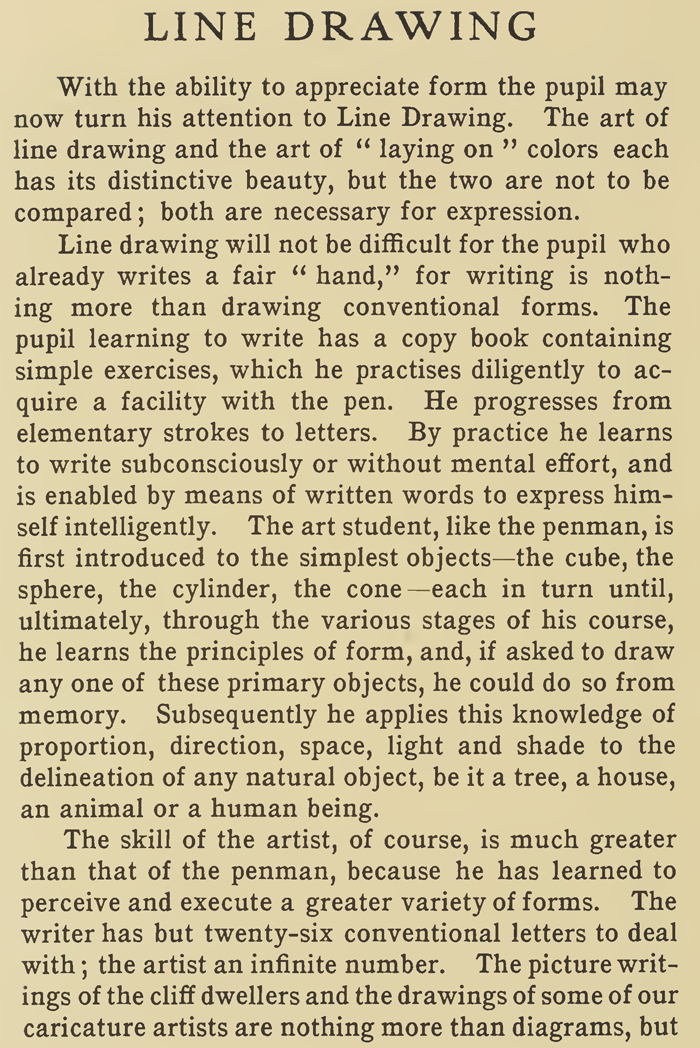

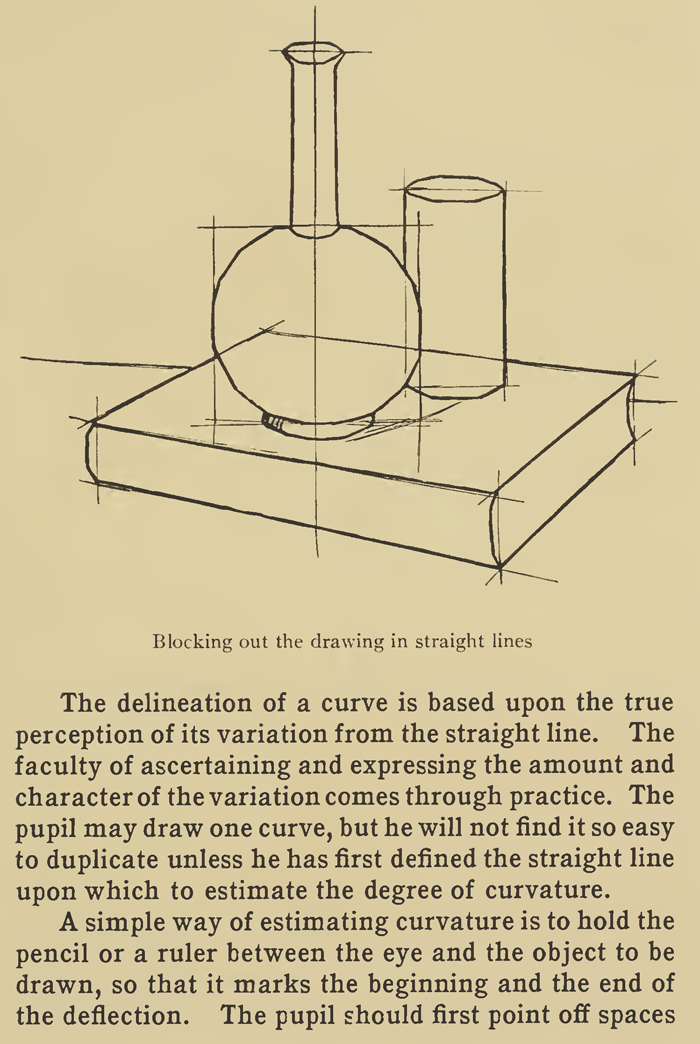

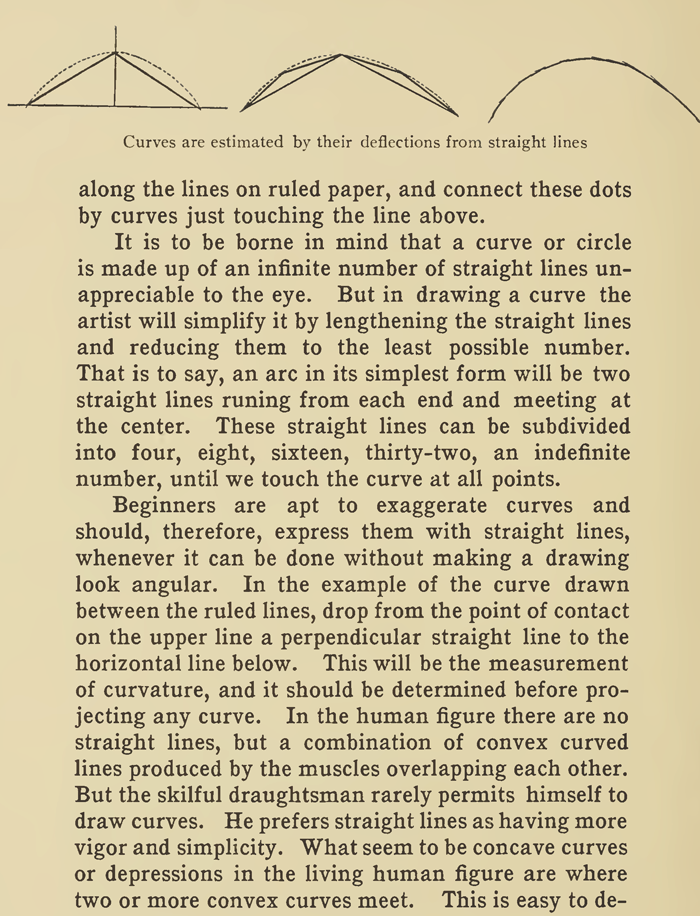

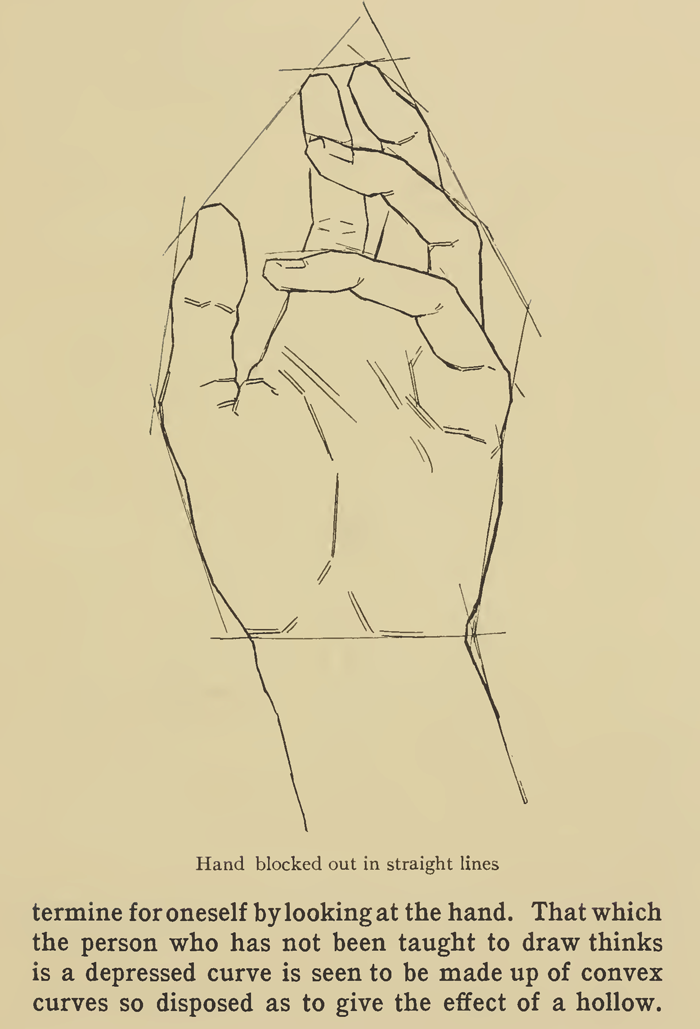

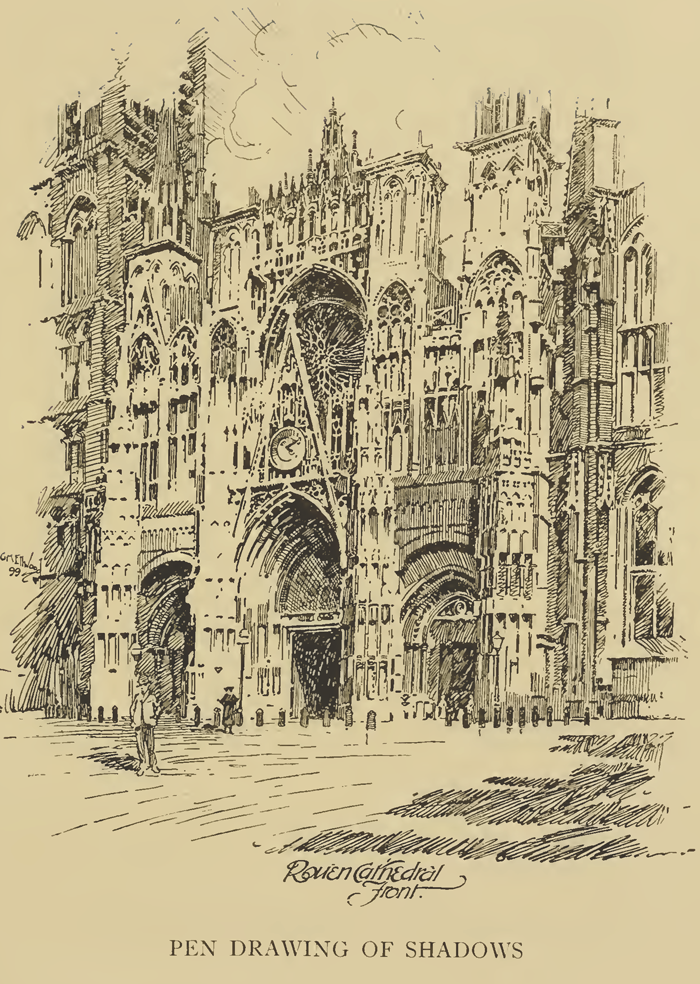

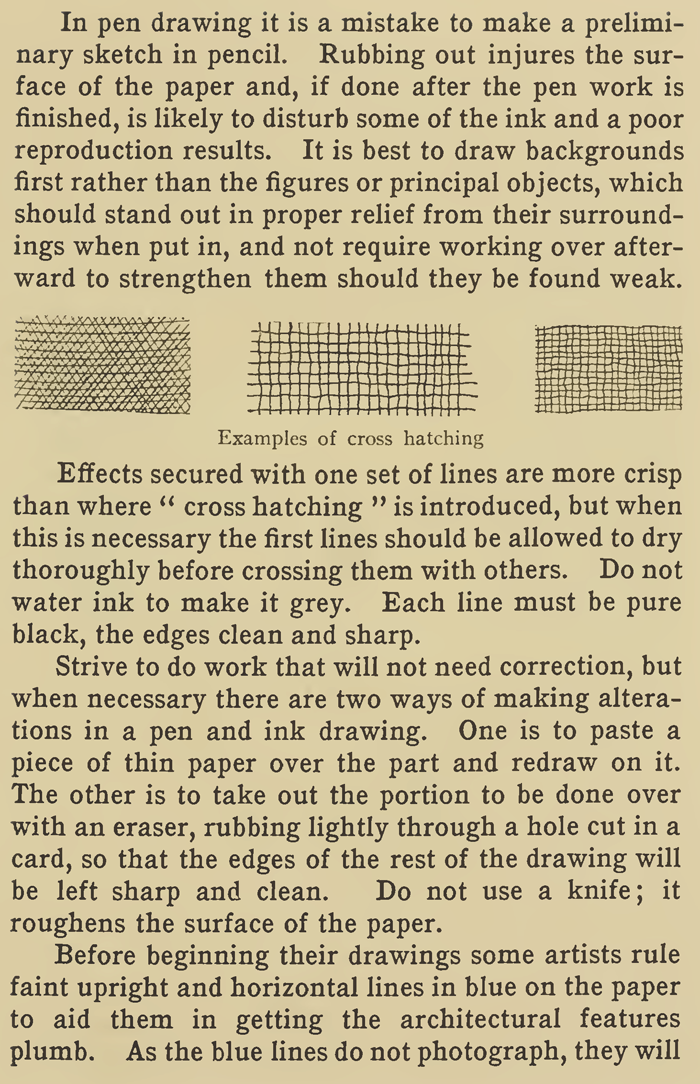

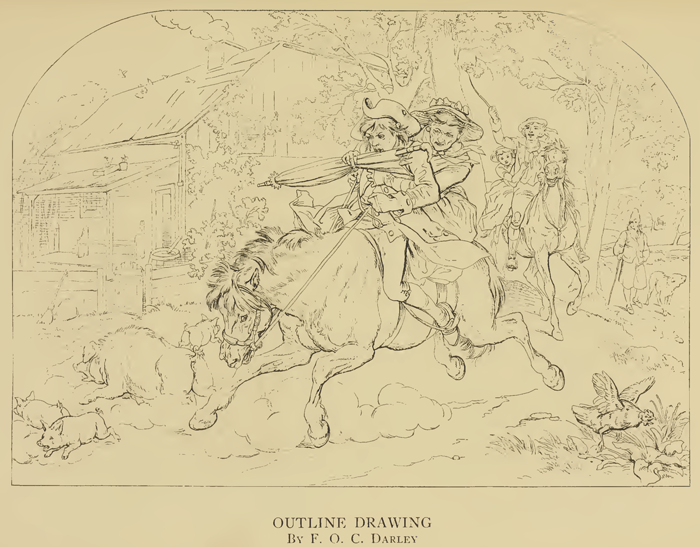

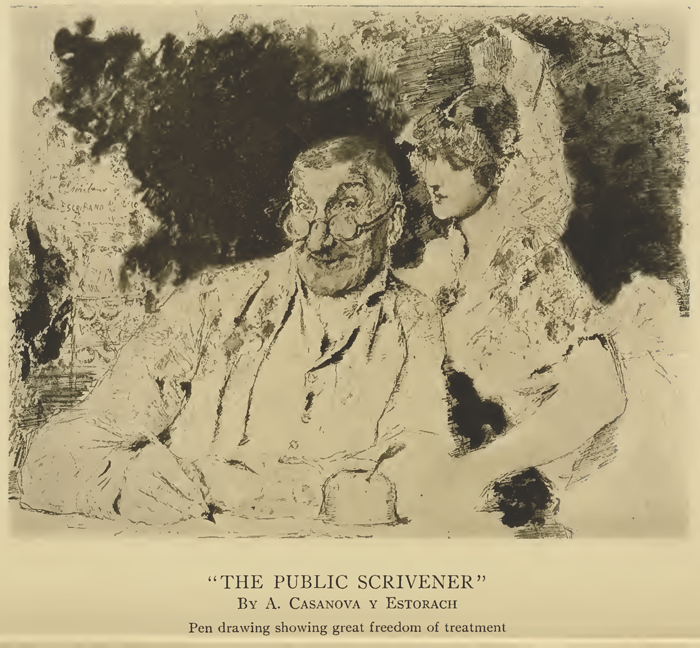

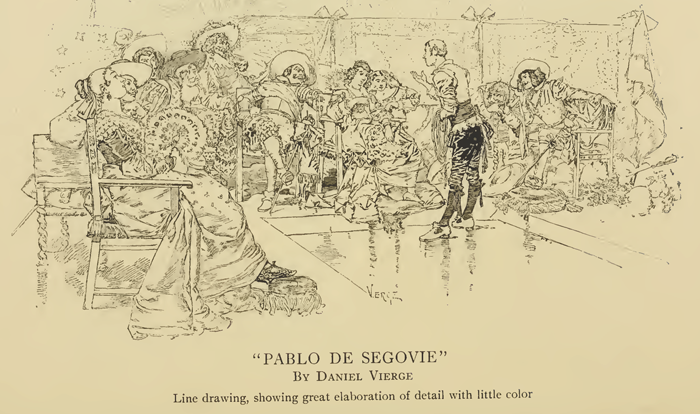

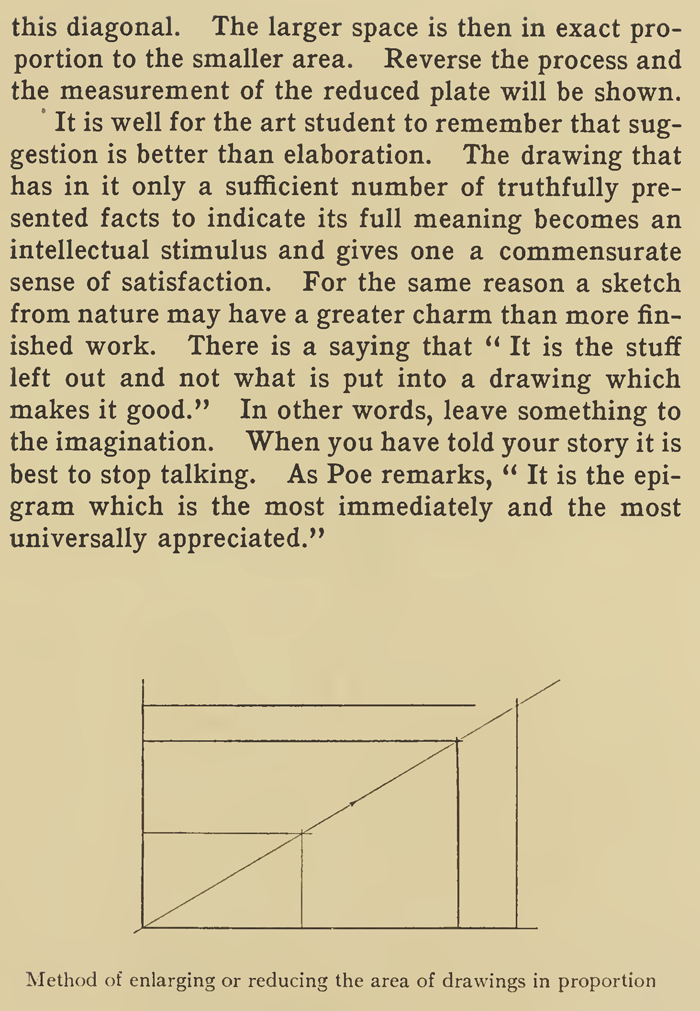

The text above is made up of images, to copy some text, it is below. LINE DRAWING with Pen and InkWith the ability to appreciate form the pupil may now turn his attention to Line Drawing. The art of line drawing and the art of " laying on " colors each has its distinctive beauty, but the two are not to be compared ; both are necessary for expression. Line drawing will not be difficult for the pupil who already writes a fair " hand," for writing is nothing more than drawing conventional forms. The pupil learning to write has a copy book containing simple exercises, which he practices diligently to acquire a facility with the pen. He progresses from elementary strokes to letters. By practice he learns to write subconsciously or without mental effort, and is enabled by means of written words to express himself intelligently. The art student, like the penman, is first introduced to the simplest objects—the cube, the sphere, the cylinder, the cone —each in turn until, ultimately, through the various stages of his course, he learns the principles of form, and, if asked to draw any one of these primary objects, he could do so from memory. Subsequently he applies this knowledge of proportion, direction, space, light and shade to the delineation of any natural object, be it a tree, a house, an animal or a human being. The skill of the artist, of course, is much greater than that of the penman, because he has learned to perceive and execute a greater variety of forms. The writer has but twenty-six conventional letters to deal with ; the artist an infinite number. The picture writings of the cliff dwellers and the drawings of some of our caricature artists are nothing more than diagrams, but they convey their meaning. The higher phases of art are but a development of the diagram, coming closer and closer to the interpretation of individual character, until we reach the portrait painter, who produces a likeness and at the same time interprets the personality and temperament of his subject. And so it is seen that drawing and writing are comparable, and the skill required varies only in degree. The artist is ever on the alert to acquire new characters for his alphabet, and it is by accumulating bits of knowledge here and there that he eventually secures a vocabulary with which to give his thoughts artistic expression. The greater the number of words or sentences retained in his memory the greater are his resources in the language of art. It is not to be understood that the artist does not forget many things, and for that reason he constantly refreshes himself at the fountain of nature and verifies his work by the aid of models. But the artist is not a camera which can only record what it sees. The greatest care is necessary in study so that no imperfect impressions find lodgment in the memory to stifle and confuse the precise and definite. As the pen requires accuracy and precision, its use is advised for line drawing. Those who begin with the pencil in one hand and a rubber in the other, will soon find, however convenient the latter may be, that it induces carelessness, a habit that is difficult to overcome. The pencil or charcoal is each good in its place, but not in the hands of beginners. In his first exercises the student will closely observe the beginning, direction and termination of a short straight line and then draw the line with one stroke of the pen. It may aid the pupil to practice-on ruled letter paper. Trace the lines from left to right and from right to left, making each stroke distinct and clear. Endeavor to draw at once with confidence, not with uncertain touches, as if feeling the way. When some degree of skill is thus obtained, lay aside the guide and draw without its aid. There will be found some difficulty in making continuous lines of great length, for the hand is likely to get in the lead of the sight and stray from its proper direction. When the pen does go wrong, stop and draw the line over again. Practice until you can accurately draw horizontal, upright and oblique lines and make others parallel to them. EXAMPLES OF PEN AND INK STROKES THAT SHOULD BE AVOIDEDA number of parallel lines close together and evenly spaced make a tint, but a mixture of light lines and dark lines or thick lines and thin lines produce uneven textures. Each mass of lines should be the same color throughout and the outline of the space covered clearly defined. These flat tones can be made to express modeling and every degree of light and shadow. This is only a mechanical method of rendering tones and values, just as the painter does in color. A student should become proficient in this broad handling before he attempts graduated tints, which are not so vigorous or direct. The delineation of a curve is based upon the true perception of its variation from the straight line. The faculty of ascertaining and expressing the amount and character of the variation comes through practice. The pupil may draw one curve, but he will not find it so easy to duplicate unless he has first defined the straight line upon which to estimate the degree of curvature. A simple way of estimating curvature is to hold the pencil or a ruler between the eye and the object to be drawn, so that it marks the beginning and the end of the deflection. The pupil should first point off spaces Curves are estimated by their deflections from straight lines along the lines on ruled paper, and connect these dots by curves just touching the line above. It is to be borne in mind that a curve or circle is made up of an infinite number of straight lines unappreciable to the eye. But in drawing a curve the artist will simplify it by lengthening the straight lines and reducing them to the least possible number. That is to say, an arc in its simplest form will be two straight lines running from each end and meeting at the center. These straight lines can be subdivided into four, eight, sixteen, thirty-two, an indefinite number, until we touch the curve at all points. Beginners are apt to exaggerate curves and should, therefore, express them with straight lines, whenever it can be done without making a drawing look angular. In the example of the curve drawn between the ruled lines, drop from the point of contact on the upper line a perpendicular straight line to the horizontal line below. This will be the measurement of curvature, and it should be determined before projecting any curve. In the human figure there are no straight lines, but a combination of convex curved lines produced by the muscles overlapping each other. But the skilful draughtsman rarely permits himself to draw curves. He prefers straight lines as having more vigor and simplicity. What seem to be concave curves or depressions in the living human figure are where two or more convex curves meet. This is easy to de- The artist should think out his picture and see it in his mind's eye before beginning work on it. He must have a well-defined idea of what he intends to do. If a painter, for instance, wishes to put a tree into a landscape he decides exactly what kind of a tree it shall be and makes the necessary studies for it, whereas some draughtsmen will draw the oak, the elm, the birch or the maple all alike, and make conventional foliage do duty for the African jungle as well as the Italian garden. But the artist should know that trees have individualities, just as men and women have, and that the most insignificant object demands truth in its portrayal. After intention must come conception. By conception is not meant the creation of new forms but the reestablishment of mental images sufficiently characteristic to enable the artist to assemble them in an orderly way in relation to each other, so that they will express his idea when developed on the paper or canvas. Of course there can be no adequate conception of a thing without a thorough knowledge of its structure and detail. This intimate knowledge comes from association with it, but our impression is liable to be vague unless fixed in the memory by the art of drawing. The conception, clear and distinct, must be ever present during the work. It should be so fixed that no variation or change from it will be necessary. By vacillating from one idea to another, by rearrangement or introducing afterthoughts, no great work of art is possible. Supposing an artist started a picture in bright sunlight, when everything was aglow with color, and while he kept on painting the sky became overcast and a mist rose to befog the landscape. The first work would become gradually obliterated. And to carry the absurdity still further, if the sun came out again with the artist still at his painting, the picture at the end of the day would be nothing but a patchwork of unrelated parts. The figure painter who intends to depict some great historical event will think over the subject for months, possibly for years. He makes innumerable notes and preliminary sketches until the composition and characters become so vivid in his imagination that the empty canvas is as the completed picture to him. Every part has been considered, decided upon, all his materials, costumes and models have been selected ; he is ready to begin work. With a few strokes he indicates the location of the figures ; a fold of drapery falls into place, architectural features take shape, broad masses of light and shadow are indicated. The artist paints here a little, there a little, all over at once—no one part given more importance than another. The man who is his own master completes the picture with decision. How labored the production if with every passing fancy a change had been made. The painting would never be finished. Conscientious painters never attain their ideals, but a greater degree of excellence is secured by working from an adequate conception. In pen drawing it is a mistake to make a preliminary sketch in pencil. Rubbing out injures the surface of the paper and, if done after the pen work is finished, is likely to disturb some of the ink and a poor reproduction results. It is best to draw backgrounds first rather than the figures or principal objects, which should stand out in proper relief from their surroundings when put in, and not require working over afterward to strengthen them should they be found weak. Effects secured with one set of lines are more crisp than where " cross hatching " is introduced, but when this is necessary the first lines should be allowed to dry thoroughly before crossing them with others. Do not water ink to make it gray. Each line must be pure black, the edges clean and sharp. Strive to do work that will not need correction, but when necessary there are two ways of making alterations in a pen and ink drawing. One is to paste a piece of thin paper over the part and redraw on it. The other is to take out the portion to be done over with an eraser, rubbing lightly through a hole cut in a card, so that the edges of the rest of the drawing will be left sharp and clean. Do not use a knife ; it roughens the surface of the paper. Before beginning their drawings some artists rule faint upright and horizontal lines in blue on the paper to aid them in getting the architectural features plumb. As the blue lines do not photograph, they will not show in the reproduction. Fine bristol board is the best paper for pen drawing. A grained surface may be more agreeable to work upon than a smooth one, but the lines will always come ragged when reproduced. It is unwise to use white on a drawing. After everything else has been finished, lights may be picked out with a sharp knife. For large drawings quill pens are sometimes useful. There is nothing so pliant in skilled hands as these serviceable tools, once extremely popular with artists, and it may not be amiss to note how they are made. The quill should be scraped on the side where it is to be split, first toward the point and then backward, much or little, according to the flexibility of the nib desired, then cut off the end. Start the split with the knife and run it up with the right thumb nail. The rule for a writing-pen is to cut the shoulders the length of the split, but for drawing some variation may be necessary. The right nib, as you hold the pen, should be a little the longer of the two, to produce a delicate line. Examine your pen lines under a magnifying glass to see if they are sound —that is, perfectly black, without rotten spots or fuzzy edges. A little care in this direction may keep your work in favor with the engraver or publisher, and it is prudent and politic to avoid putting the latter to extra expense for finishing plates made from faulty drawings. Textures and surfaces may be expressed by the pen line—some by upright lines, others by horizontal lines. One draughtsman gets his effects by broad, coarse handling, another by fine, delicate treatment. But generally speaking, the finer lines in a drawing recede and convey the impression of distance, while coarse strokes advance and are more suitable for foregrounds. An outline looks softer when the preliminary sketchy lines are not erased and their retention adds life and atmosphere ; not necessarily do they indicate lack of knowledge. A beginner invariably makes the mistake of striving for detail and pottering over the unimportant in a drawing because he takes pleasure in doing that which looks pretty. But such work disturbs the repose of a composition. The eye goes to detail almost as quickly as to concentrated light in a picture. In finishing a drawing there may be parts which need a few extra touches to enhance the interest, but detail should be added sparingly. Keep the work as a whole constantly in mind. The size of a drawing for reproduction can be left to the judgment of the artist. Some make their drawings four or five times larger than the illustration is to be, but twice the size is ample. It is well to settle for all time what reduction is best suited to one's handling. Reproduced by the photo-engraving process a drawing is much refined, and a reducing lens, to be had of any dealer in optical goods, will show what this refinement will be when the drawing is brought down to the plate size. The proportions of a drawing to fit a given space are fixed by a very simple method of measurement. Say a picture must be reduced to exactly three by five inches. Measure off this area and rule up the form with a T square, projecting a line through the two corners of this space and beyond it, and drawing upright and horizontal lines perfectly square to meet on this diagonal. The larger space is then in exact proportion to the smaller area. Reverse the process and the measurement of the reduced plate will be shown. It is well for the art student to remember that suggestion is better than elaboration. The drawing that has in it only a sufficient number of truthfully presented facts to indicate its full meaning becomes an intellectual stimulus and gives one a commensurate sense of satisfaction. For the same reason a sketch from nature may have a greater charm than more finished work. There is a saying that " It is the stuff left out and not what is put into a drawing which makes it good." In other words, leave something to the imagination. When you have told your story it is best to stop talking. As Poe remarks, " It is the epigram which is the most immediately and the most universally appreciated." Method of enlarging or reducing the area of drawings in proportion |

Privacy Policy ...... Contact Us